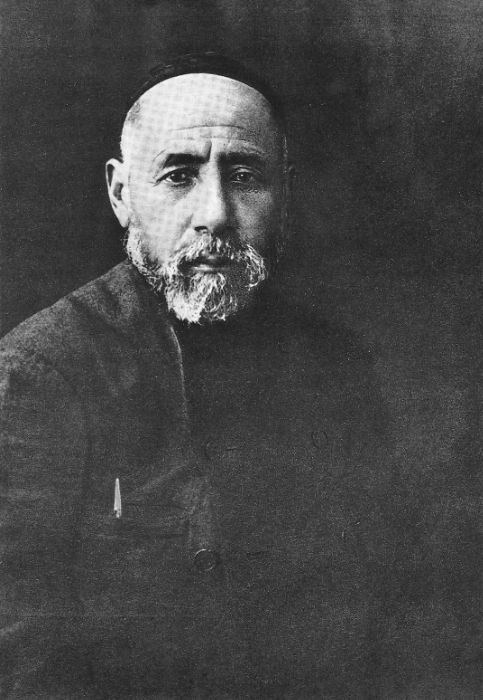

Sadriddin Ayni -- Tajik National Hero

•

by

•

by SaintPetersbourg

Садриддин Саидмуродзода (Sadriddin Saidmurodzoda) (Ayni was a pen name chosen by him later in his life) was born in Soktare in the province of Ghijduvon within the Bukhara Emirate on April 15, 1878.1 He spent his youth between the two villages of Soktare and Mahallayi Bolo. Soktare was a village near the river Zarafshon with much fertile ground and a large mosque renowned for its exorcists and prayer healers, whereas Mahallayi Bolo was an unremarkable village that during Ayni’s lifetime would become extremely poor and all but cease to exist.2 Although Ayni attended the village school attached to the mosque in Soktare, as he describes in one of his autobiographical works, Мактаби кӯҳна, he did not learn anything in his time there, and learned only very basic literacy at the girls’ school he later attended. Everything of value that Ayni learned during his childhood he learned from his father. According to Ayni, it was only in his adult life that he finally learned how to read properly.3

After both of Ayni’s parents died of cholera in 1889, Ayni abandoned his childhood dream of studying in Bukhara and becoming a poet, forced instead to take over the family’s fields to provide for his younger brothers. 11-year-old Ayni’s incompetence at farming, as well as the large amount of debt incurred by his parents’ funerals, forced him to sell the family home at Mahallayi Bolo. While visiting an aunt, Ayni was able to impress a great scholar visiting from Bukhara with his knowledge of spelling, and the scholar (Шарифҷон Махдум) invited him to Bukhara to study, an invitation Ayni accepted gratefully, leaving his brothers behind with his aunt in Mahallayi Bolo.

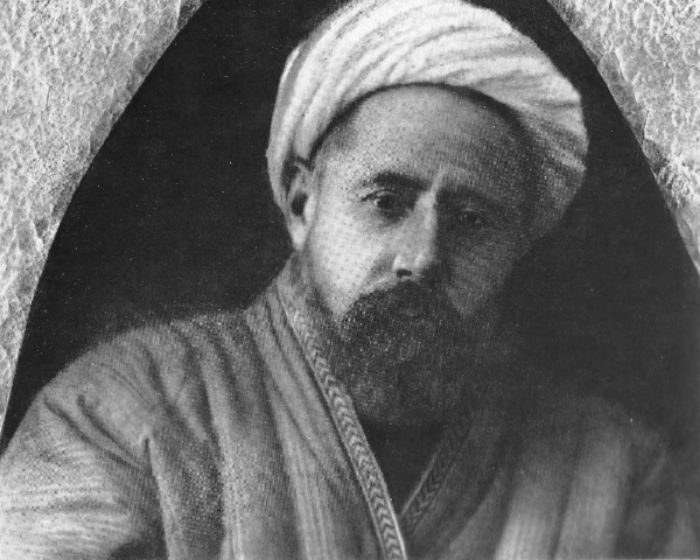

In Bukhara, Ayni attended numerous madrasas, but felt stifled and uninterested in their limited and impersonal religious teaching. He became involved with small, illicit student circles, which studied things like history, math, and current events—all things forbidden by the emir. Gradually, as the poetry that Ayni began to write became known in intellectual circles, Ayni was increasingly included in secret meetings of the literati to discuss topics ranging from literature to social injustice. Ultimately, Ayni became a staunch supporter of the Jadid movement (a Central Asian movement for the modernization [hence the name] of education), dedicating himself to what he deemed to be the solution to the problems that plagued Bukhara at the time: education reform.4

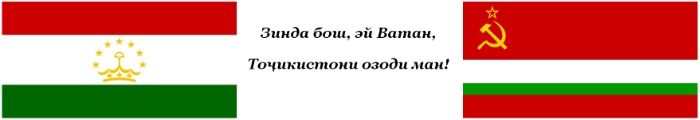

After the establishment of the USSR in 1917, Ayni moved to Samarkand (then a part of Soviet Turkestan) after being beaten and imprisoned by the emir’s police in Bukhara. Shortly afterward, he began to write poetry and music praising the communist revolution and criticizing the emir’s regime. Ayni was one of the principal contributors to the communist journal ‘Шуълои Инқилоб,’ urging for a people’s revolution, and encouraging people to join the Red Army.5 Eventually he began to favor prose over verse as a means of expression, writing novels instead of poetry describing the evils of the emir and the need for education reform. He began to advocate that intellectuals stop writing poetry, and focus on writing prose every man could understand.6

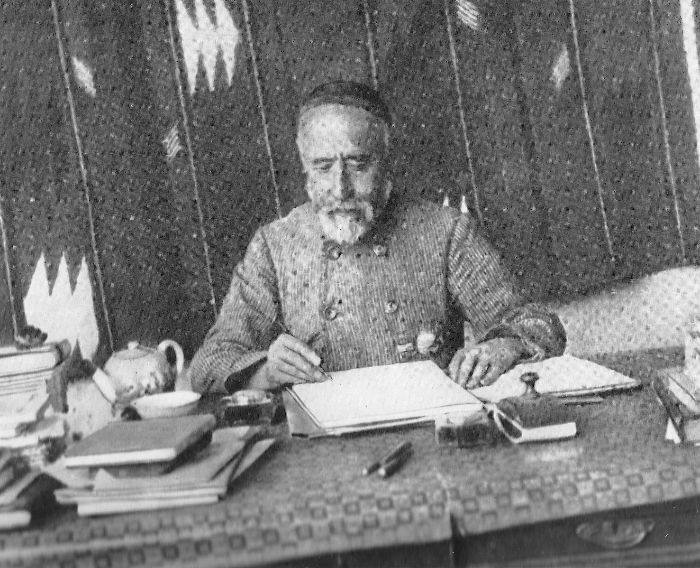

After the fall of the emir and the establishment first of the Tajik ASSR in 1924, and then of the Tajik SSR in 1929, Ayni turned his attention away from politics and entirely to the issue which most concerned him, education. He devoted himself to the task of creating a new Tajik language. According to the Tajik press, “Until the Revolution there was a great difference between the literary Tadzhik language and spoken Tadzhik.” Furthermore, students, and even teachers, whose first language was Tajik were unable to write grammatically.7 In addition to his rejection of ‘literary’ grammar and style, Ayni eschewed Arabicisms, archaisms, Iranianisms, and dialecticisms, and favored international equivalents (imported from Russian). According to Маъсумӣ’s “Essays about the Development of the Tajik Literary Language,” “Ayni’s works of fiction winnowed out elaborate phraseology and obsolete vocabulary and spoke directly to the growing mass audience.”8 9 Furthermore, Ayni was well known for receiving a copy of all things published by the Tajik press and contacting their authors about “linguistic slips, unsuitable words and word connections, [etc. …] which all of them considered an honour.”10

Over the course of his lifetime, Sadriddin Ayni single-handedly standardized and created the Tajik language, published hundreds of works of almost every genre, and reformed the education system of the Uzbek and Tajik SSRs. When he died on on July 15, 1954 in Dushanbe, he was canonized as one of Tajikistan's National Heroes, and has been awarded two Lenin awards among numerous other Soviet medals of distinction. Even today his influence can be seen in anything published in Tajikistan, and numerous places and important buildings are named after him, including the famous Ayni Opera House in Dushanbe.

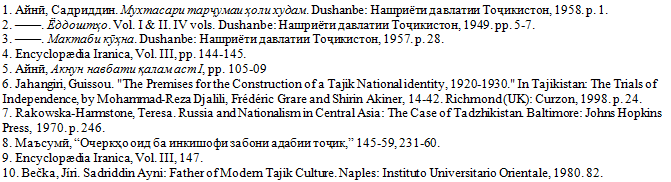

Citations

This is my first article ever and written as a part of the ILP Writing Contest as advertised here.

Comments

Damn, citations and everything. Good work!

wow this is a great article! o/

-v-

Nothing like jumping in the deep end! Good start and welcome to the Irish Writers Literary Guild.

popped out of my temporary hiatus to heap praise on this article

Damn. This'll be tough to beat..

Thanks for all the comments and encouragement, guys. I wrote it as a break from studying for my Sanskrit final, and now I'm final done with all my final exams. Let the summer begin!