[Stilpo] Bonus Section Results - August

•

by

•

by Stilpo

Hello again Ireland,

I have been putting this off for a while now, but I have finally gotten around to analyzing the bonus section of the August government evaluation survey. Below are the results of this analysis in full, including summaries and conclusions to sum up the major findings for the TL😉

R crowd.

SUMMARY

This analysis uses data from the August survey to answer several questions: (1) how, if at all, is party membership related to things like ideology, priorities or personality; (2) how, if at all, is ideology related to personality; and (3) is there a single overarching ideological dimension (or 2-dimensional plane) that connects the various ideological dimensions in eRepublik?

Among other things, I uncover the interesting pattern that, although most citizens report that economics is the least important ideological dimension in this game (and that ideology in general is the least important function of a party), it is in fact in-game economic orientation that is most predictive of party membership in eIreland – at least for certain parties such as ILP and SUI. However, even this accounts for only a small proportion of the variance in overall party membership.

I also find that, while personality traits have little direct impact on party choice, certain traits (such as neuroticism and extraversion) are weak but significant predictors of ideology.

And, last but not least, statistical analysis found no systematic variation between ideological domains. Thus the various ideological domains investigated here do not appear to be connected by any sort of systematic way, suggesting no underlying ideological dimension that organizes eRepublik ideology.

Possible interpretations of these findings are discussed in the conclusion section.

INTRODUCTION

Variables

Category 1: Ideology

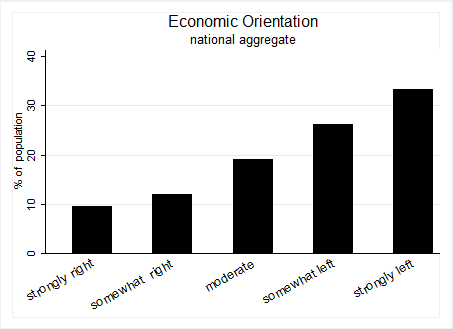

(1) Economic Orientation (left vs. right)

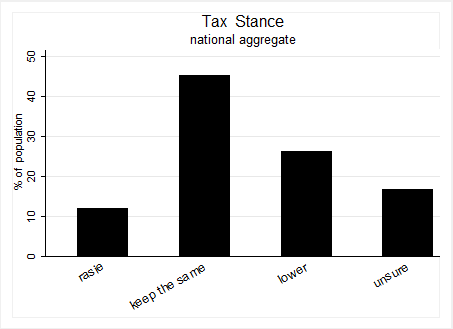

(2) Tax Stance (higher vs. lower)

(3) Foreign Stance (aggressive vs. defensive)

(4) Foreign Orientation (nationalist vs. internationalist)

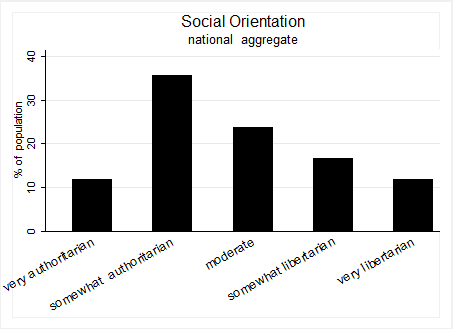

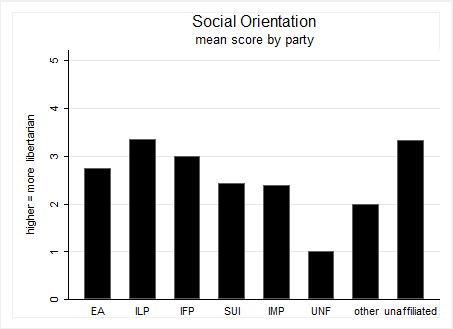

(5) Social Orientation (libertarian vs. authoritarian)

Category 2: Priorities & approach

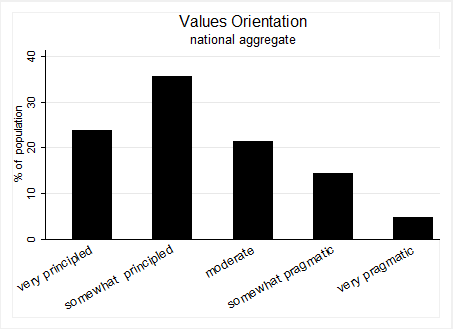

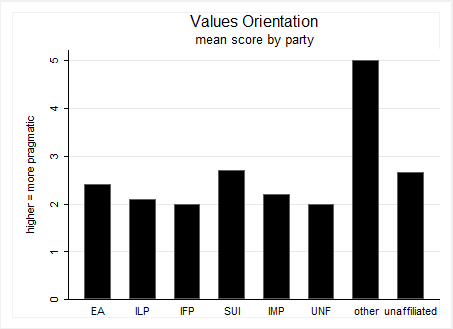

(1) Values Orientation (pragmatism vs. principles)

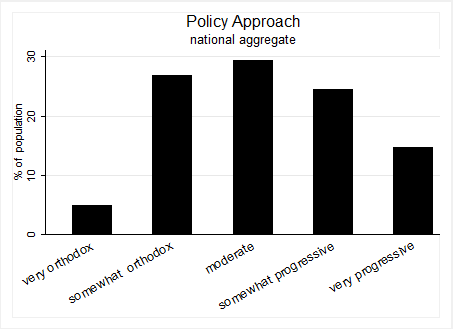

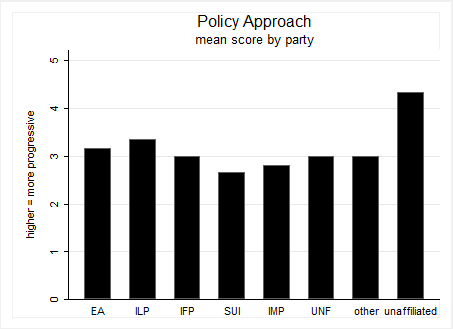

(2) Policy Approach (orthodox vs. progressive)

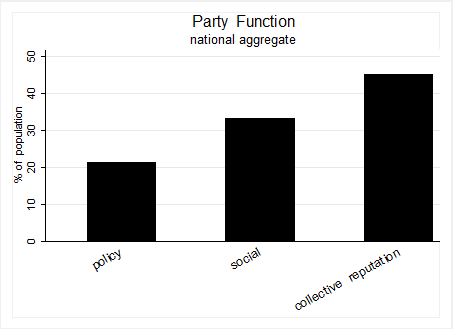

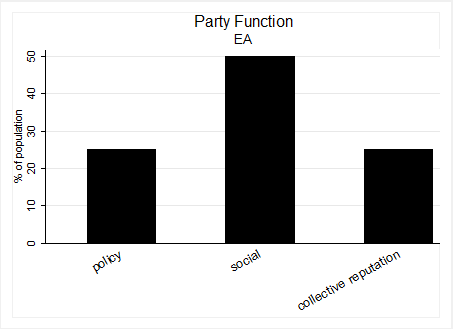

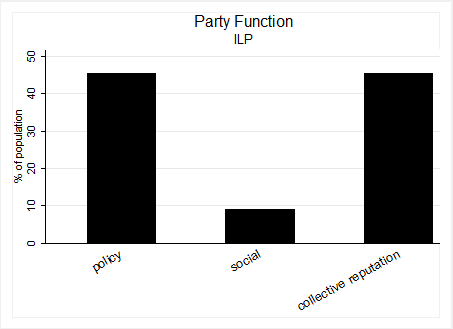

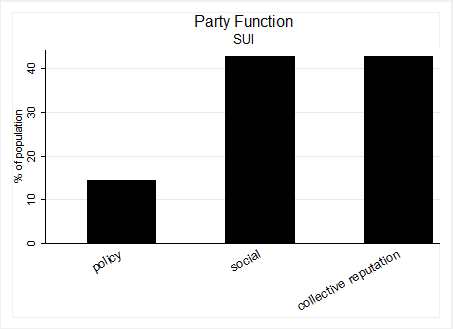

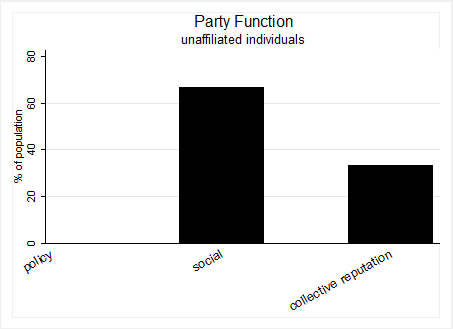

(3) Party Function (policy vs. social vs. reputation)

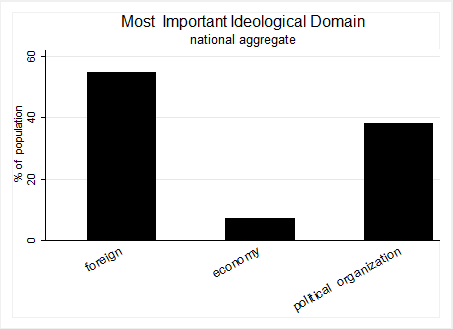

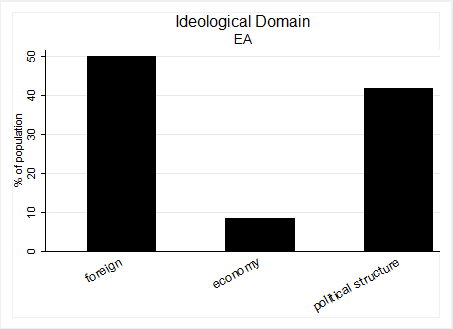

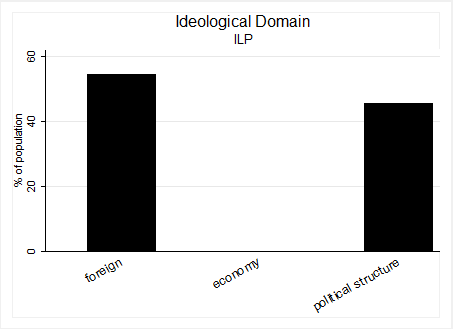

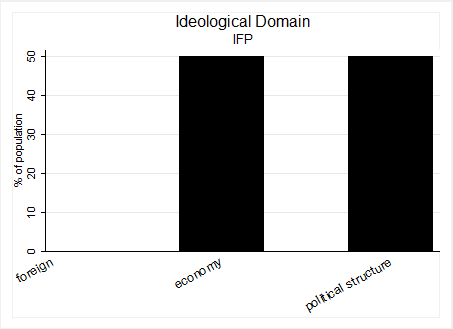

(4) Most important ideological domain (foreign vs. economic vs. social-political organization)

Category 3: Personality (i.e. “big-five” traits)

(1) Extraversion

(2) Agreeableness

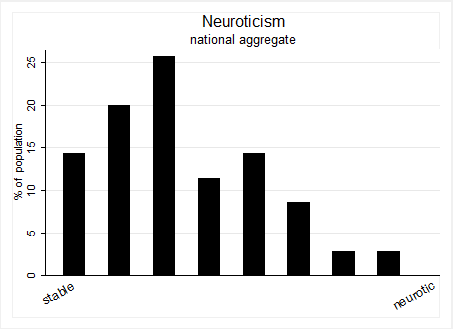

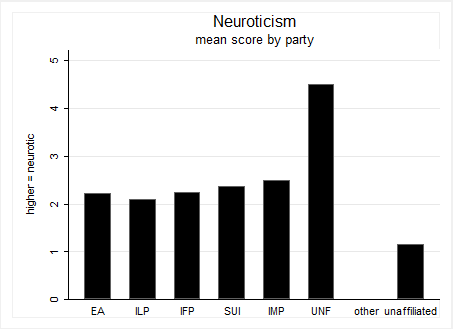

(3) Neuroticism

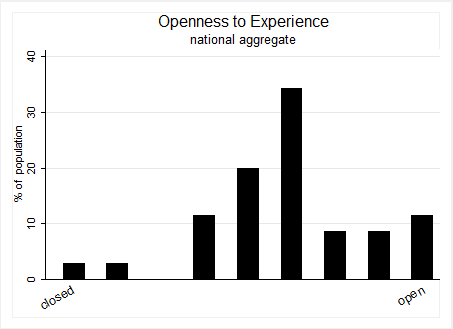

(4) Openness to Experience

(5) Conscientiousness

It is important to note that ideological domains were measured by asking participants to place themselves on artificially-conceived ideological dimensions. Such dimensions were used simply because certain policies seemed to “go together” in my mind (for example, a ‘left’ economic orientation is defined as supporting centralized supply or support systems and communes (vs. free association and competitive markets), which is unrelated to views on taxes in this game). However, there is no guarantee that they in fact represent true eRepublik ideological distinctions. Thus this analysis should be viewed as an investigation of my own conception of eRepublik ideology rather than actual eRepublik ideology. There is also no guarantee that people were reporting their true eRepublik ideological leanings instead of just reporting their real-life ideology. In any case, results should be interpreted with caution.

The reason I included personality traits in this investigation because some scientific studies in real-life have shown that personality may be related to party identification. For example, Republicans in the United States tend to score higher than Democrats on measures of conscientiousness, and lower on measures of openness to experience. While both the direction of the causal arrow and the ultimate meaning of this relationship is still a matter of debate among researchers, I thought it might be fun to see if personality had an impact on party identification in eIrisih party choice. To measure these traits, I employed a 10-item short-version of the big five personality scale. For the more curious readers, the exact scale and coding procedures for this scale can be found here.

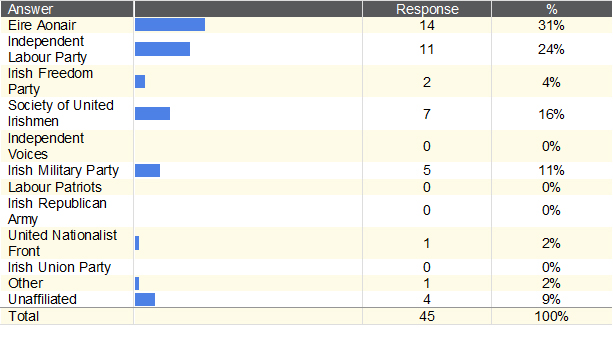

Survey Participation

Before we jump into the meat of things, it is important to review the makeup of those who took the survey. Below is a re-print of the participant profile found in the August Government Evaluation Survey. We had very good participation in August with 45 people from at least six different Irish parties completing the poll. It is worth noting, however, that the parties Independent Voices, Labour Patriots, Irish Republican Army, United Nationalist Front, and the Irish Union Party did not have enough participants to be included in the analysis. IFP members had just enough participants to be included in the analysis, but the low turnout compared to other parties may have reduced the chance of detecting statistically significant relationships for this party. Indeed, there are several graphs where IFP appears to score differently on some measure than other parties, but the difference is not found to be statistically significant. Thus, all results in this analysis should be read with an appropriate level of skepticism regarding the generalizability of the conclusions to all parties in eIreland.

PART 1: PARTY CHOICE

Statistical approach

CAUTION: Do not read this section if your IQ is less than 50. It may make you cry.

Unless otherwise stated, all party choice analyses were tested using a series of bivariate multinomial logistic regression models. This type of model was chosen because it is uniquely designed to estimate the statistical effect of various types of predictors on a categorically-distributed dependent variable such as party affiliation in a multi-party system. A bivariate approach was chosen over a multivariate approach because the relatively small sample size led to issues of over-fitting and degeneration of the model when more than four predictor variables were included (especially when personality variables were included, which had an even lower response rate). I will spare you the technical details of exactly how multinomial logit models work, but suffice it to say that the procedure results in in elaborate series of estimations of the likelihood that each independent variable results in membership in one party vs. each other party. In other words, we cannot say that a variable is a statistically significant predictor of party membership in general, but we can say that it is a significant predictor of membership between one party and some other specific party. For example, economic orientation is found to be a predictor of ILP vs. EA and SUI vs. EA but not ILP vs. SUI.

However, a significant degree of caution is urged of the reader when interpreting any of these results. Not only can a small sample size exaggerate or mask relationships that would be found in the larger population, but there are also several other statistics-related issues that the critical reader should be aware of:

(1) Because a bivariate rather than a multivariate approach was employed, it is important to be aware that shared effects between independent variables are not controlled for in this analysis. Because of this, we cannot say for certain whether the effects we uncover are unique to a specific variable or are actually driven (wholly or in part) by some other related variable. Thus, all statistical tests represent a sort of upper bound to the possible contribution of that variable to party choice.

(2) I would also like to remind the reader that a test of statistical significance in-and-of-itself does not actually tell us anything about the nature of the relationship being tested. In other words, it does not tell us anything about how much of an impact a predictor may have on party choice. Rather, statistical significance only tells us we can be reasonably certain that relationship is likely to be “real” rather than a result of random fluctuations in the data, regardless of whether that relationship itself is weak or strong. Normally, a statistician would look at things like the properties of the regression coefficients and R-squared values to get a better sense of the actual nature of a relationship, but these parameters can be tricky to interpret (especially non-linear ones as in this model). Thus, the best way to get a sense of the nature of a relationship is to simply compare the means visually in the graphs provided below (but only if our test of statistical significance tell us that the apparent relationship is unlikely to be due to chance).

(3) It is also important to note that a liberal approach was also used in reporting the results of statistical tests. Namely, I included “marginally” significant (pany effect that is reported to be only marginally significant is more likely to be a false positive (5%-10% chance) compared to effects that are found to be traditionally significant (1%-5😵

and high significant (less than 1😵

. However, the level of significance is always indicated in the report, ultimately allowing the reader to decide how conservative or liberal they wish to be in interpreting the results.

Final note:: If for some ungodly reason you are a genuine statistics buff and are interested in the technical details of the statistical modeling or results or diagnostics, or have any other statistics/methods-related questions regarding this analysis, feel free to PM me with your request and I will do my best to accommodate you. Anyone is also welcome to request the raw data in either spreadsheet or .dta form (minus any identifying information about the participants) to analyze themselves.

Now that all the mind-numbing statistical business is out of the way, on to the results!

Results

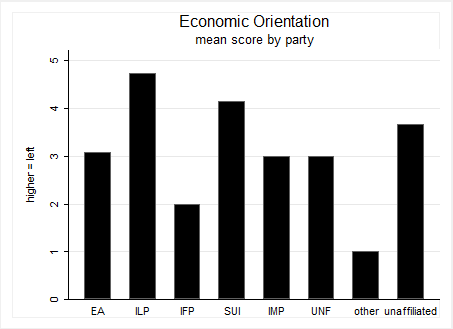

Economic Orientation (left vs. right)

Statistically Significant Relationships: YES

- ILP vs. unaffiliated (significant)

- ILP vs. IMP (highly significant)

- ILP vs. EA (highly significant)

- ILP vs. IFP (highly significant)

- SUI vs. IMP (marginally significant)

- SUI vs. EA (marginally significant)

- SUI vs. IFP (significant)

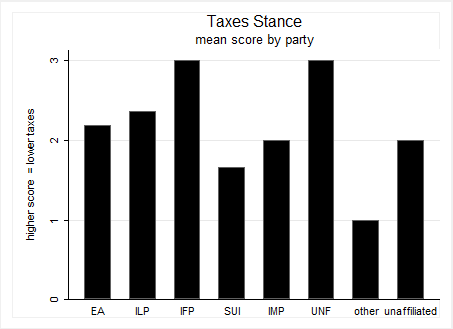

Tax Stance

Statistically significant relationships: YES

- unaffiliated vs. IFP (marginally significant)

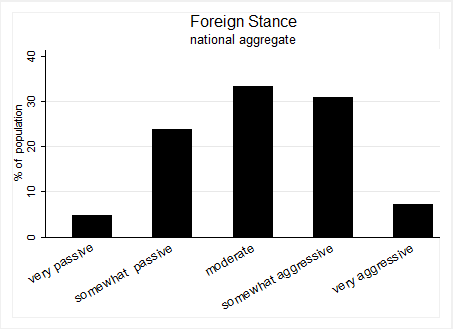

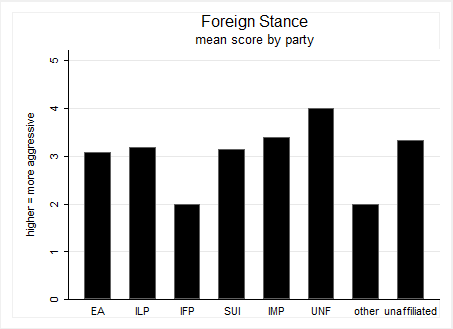

Foreign Stance (aggressive vs. defensive)

Statistically significant relationships: NO

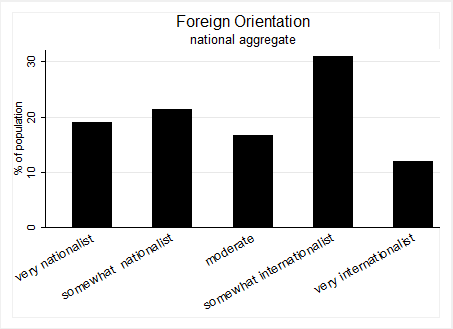

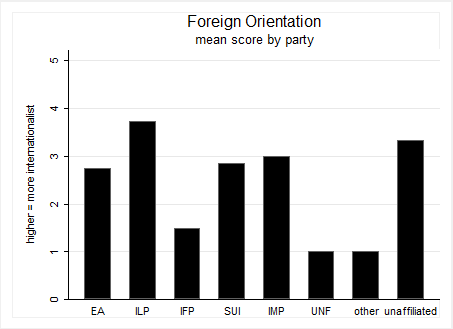

Foreign Orientation (nationalist vs. internationalist)

Statistically significant relationships: YES

- ILP vs. EA (marginally significant)

- ILP vs. IFP (marginally significant)

Social Orientation (authoritarian vs. libertarian)

Statistically significant relationships: NO

Values Orientation (principled vs. pragmatic)

Statistically significant relationships: NO

Policy Approach (orthodox vs. progressive)

Statistically significant relationships: YES

- unaffiliated vs. SUI (marginally significant)

- unaffiliated vs. IMP (marginally significant)

Party Function (which is most important?)

Statistically significant relationships: YES

- ILP vs. IMP (marginally significant)

- EA vs. IMP (marginally significant)

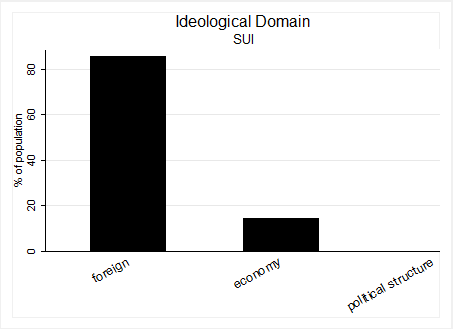

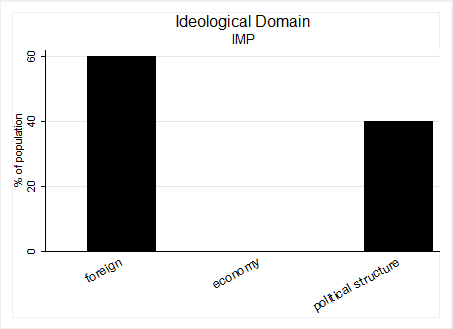

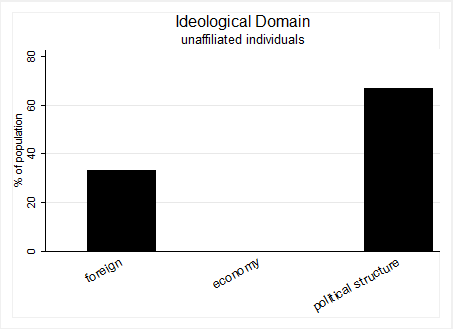

Ideological Domain (which is most important?)

Statistically significant relationships: YES

- SUI vs. unaffiliated (marginally significant)

- SUI vs. IFP (marginally significant)

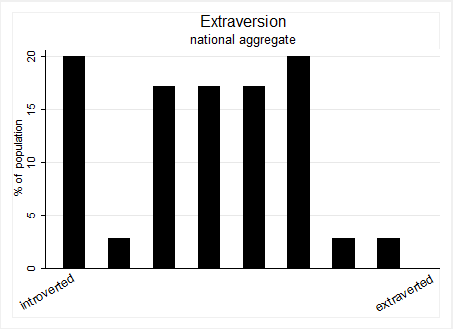

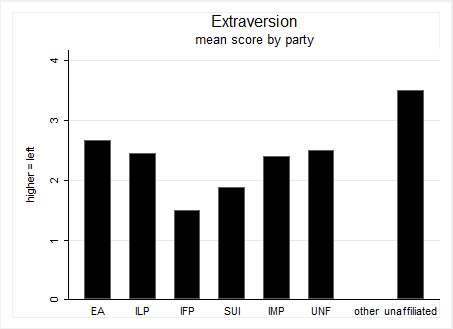

Extraversion

Statistically significant relationships: YES

- unaffiliated vs. SUI (significant)

- unaffiliated vs. IFP (significant)

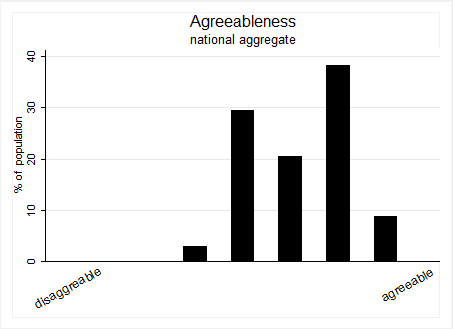

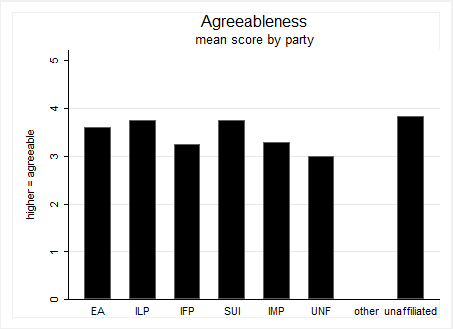

Agreeableness

Statistically significant relationships: NO

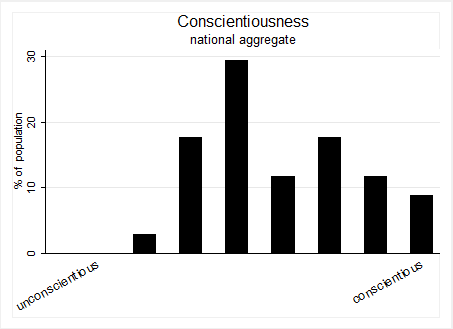

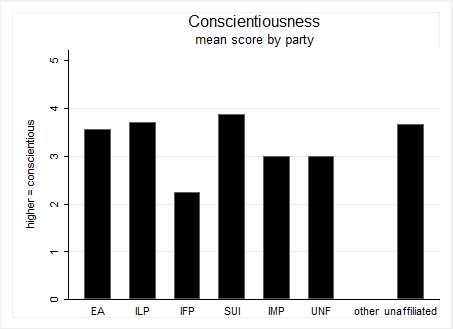

Conscientiousness

Statistically significant relationships: YES

- SUI vs. IMP (marginally significant)

Neuroticism

Statistically significant relationships: YES

- unaffiliated-IMP (marginally significant)

- unaffiliated-SUI (marginal significant)

- unaffiliated-IFP (marginal significant)

- unaffiliated-ILP (marginal significant)

- unaffiliated-EA (marginal significant)

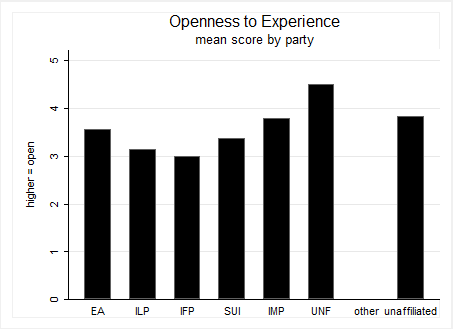

Openness to Experience

Statistically significant relationships: NO

PART II

In addition to predicting party choice, I also ran a few quick models to determine which of the personality variables, if any, predict eRepublik ideological stances.

Statistical Approach

In this section I used a series of ordered logistic regression models to determine if personality traits predict ideological placements. This analysis is similar to the multinomial logistic regression in that it does not assume a continuous DV, but it recognizes that there is an order to the levels of the DV. A linear-style regression model was not used due to other restrictive properties of the DV and the relatively small sample size. Because we do not have to break down the sample into small pieces as in the party analysis, I was able to use a multivariate approach. A separate multivariate model was run for each ideological dimension that that included all 5 of the “big five” personality traits. Thus, unlike the first part, we can be more confident that these results represent independent effects of each of the predictor variables rather than any kind of shared variation between the predictors.

Results: What does personality predict?

The aforementioned statistical models resulted in the following findings:

(1) Neuroticism was a significant predictor of social orientation, such that greater emotional stability is weakly predictive of a more libertarian (vs. authoritarian) social/political organization.

(2) Neuroticism was a *marginally* significant predictor of policy approach, such that greater emotional stability is weakly predictive of a more progressive (vs. orthodox) approach to making policy.

(3) Neuroticism was a *marginally* significant predictor of foreign orientation, such that greater emotional stability is moderately predictive of a more internationalist (vs. nationalist) foreign policy.

(4) Extraversion was a significant predictor of foreign policy stance, such that high levels of extraversion is weakly predictive of a more aggressive (vs. passive) approach to dealing with other countries.

(5) Extraversion was a *marginally* significant predictor of values orientation, such that high levels of extraversion is weakly predictive of a more pragmatic approach to policy-making.

(6) Agreeableness was also a *marginally* significant predictor of foreign stance, such that greater agreeableness is weakly predictive of a more passive approach to dealing with other countries.

In addition to personality, values orientation and policy approach were also tested as predictors of ideology, but failed to produce any significant results.

PART III

In this section, I ask the question: Are the various ideological domains connected in some systematic way?

Statistical Approach

To answer this question I employed statistical technique called an “exploratory factor analysis”. Basically the computer program analyzes the way the variables vary together given different conditions and spits out a report that suggests if a latent dimension (or two or three) can account for any of the covariance between two or more of the dimensions. This procedure works best if we have many questions on specific policies and let the program identify its own ideological dimensions, but it can also be useful to explore the relationships between our small number of self-placements on ideological variables. However, it is less likely to return positive results, especially if people did not actually understand the meaning of my artificially-conceived ideological dimensions.

Results

Although I am still a novice at this particular technique, the exploratory factor analyses that I ran failed to identify any unseen underlying dimension(s) of ideology beyond what they are already parsed into. Specifically, one-dimensional and even 2- and 3-dimensional models failed to return eigenvalues that were greater than 1, indicating that none of the dimensions that were identified accounted for more of the variation between the original variables than any one of the variables alone. The same was found when only people who considered themselves “experts” in eRepublik politics were included in the analysis.

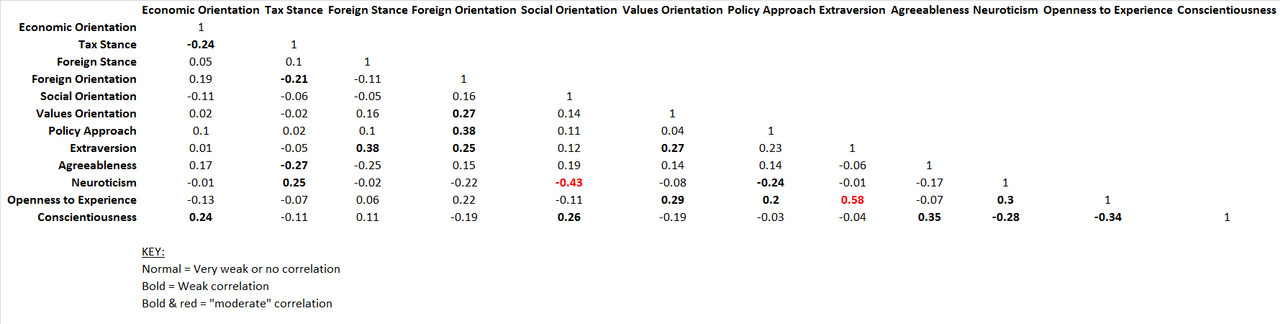

In general, this finding makes sense in light of the general lack of correlation between the various ideological domains (see intercorrelations chart for all variables below).

CONCLUSIONS:

Before forming any kind of conclusion, the reader is reminded to keep in mind that correlation does not necessarily imply causation. No matter how fancy the statistical analysis, without experimental manipulations or some sort of elaborate temporal data we cannot conclude with certainty that the variable we chose to model as the “predictor” actually causes party sorting. All we can do is point out that the two variables are related. Any assumptions of causations are ones that we make ourselves. It may very well be that party membership causes views on certain issues rather than the other way around (indeed, this is often the case in real life). Or it could be that some other factor(s) (e.g. real-life age or nationality or recreational interests or deeper values) cause both and create a spurious relationship. The point is that, although we can speculate about the direction of the causal arrow, we cannot really be certain of these speculations given the limited design of this study.

However, IF my statistical modeling is credible, some tentative conclusions we might be able to draw from this data are:

(1) Economic orientation is the greatest predictor of party affiliation, but only when it comes to ILP and SUI.

(2) Most other ideological factors are only marginally related to party affiliation , and only distinguish between one or two parties.

(3) Neuroticism and extraversion are weakly but significantly predictive of certain ideological placements and policy approaches.

(4) There is no evidence of any overarching system of thought or even a 2-dimensional plane that connects the various ideological domains. Thus, if ideological thinking exists at all (which has never actually been explored), it is only within specific domains of policy.

My own (very) tentative theory to connect all these findings is that party choice is most likely not a product of in-game ideological considerations, but rather it is due to real-life affinities such as political views (especially economic; which are often the most easy to translate to a game like this), recreational interests, real-life values, real-life age, real-life country of origin, and even a significant degree of random chance (often it is the first people we meet in eRepublik who new players tend to gravitate toward and learn from). Thus, party choice may not be strongly based in ideology, but the social pressures and insularism created by party affiliation may have an effect on the development of preferences for specific issues. This may be why there is little evidence of cross-domain systematic thinking. I would even venture to guess that, except in the case of economics, party affiliation itself (as well as personality) drives issue preferences more than ideological considerations. But of course that is just a guess. This may be something that would be a good question for future investigations.

Readers are highly encouraged to discuss their own conclusions in the comments section.

If you have any questions please let me know. You may also request to review the data in-depth for yourself, although any such data will have identifying information such as profile links removed.

Thanks for reading!

Regards,

Stilpo

P.S. If you liked this article, don't keep it to yourself!

LIST OF PREVIOUS SURVEYS:

[August 2013] National Performance Poll #4

[July 2013] National Performance Poll #3

[June 2013] National Performance Poll #2

[May 2013] National Performance Poll #1

[Nov 2012] Saoirse party performance survey

[Nov 2012] Government roles and responsibilities Survey

[Oct 2012] Policy opinion survey

[Oct 2012] Desirable traits for congress members

Comments

Very interesting. It's fun to see the ideologies behind parties reflected in actual independently completed surveys... especially when they're well defined when they touch on certain issues that different parties take to heart.

Interesting hypothesis re: what variables drive the thinking of individuals. I'd like to think that some ways of thinking are simply more objectively correct than other ofc. 😉

What ideology is yours Ian?

Considering you show open support to people who not only robbed Ireland but also betrayed irish community and joined british invaion on Ireland.

And in the same time you try to abuse an irish citizen who openly stand against those same thiefs and traitors.

Kicking him from IA for objecting traitor and thief Conway being welcomed into IA ranks.

Trying to kicking him off from irish comunity for standing his ground against corruption.

What that makes you....Ian?

I will have to read this again and sleep on it to figure out what I think it means.

Great work though.

Great work Stilpo!

Voted

Graphgasm \o/

voting an article too soon 1 sea monster. but i did see you didnt take into account how many leprechauns wants to be seen as normal citizens v how many normal citizens wants to find out how gold said leprechauns had.

also i dont think understanding or lack of understanding correlates to intelligence on a theoretical subject like statistics where a significant portion 90% have no real interest in it. thats why one gets stataistics guys that ran around everywhere and work out stuff. perhaps you can change that statement therefore.

Also why did you buy votes?

relax krakken, its just a joke

expecting the causal reader to understand or care about that section is absurd

I almost cried a little myself, and I'm a PhD student with a background in statistics

ok 🙂

WHY DIDNT YOU BUY VOTES 🙁 !!!!!

You do this in your free time? Datageek 😉

Wow.

Unsurprising that the IFP are concerned with the economy, the last bastion of capitalists that it is.

Very pleased with the overall orientation of the country.

Weird that no one in the SUI said political organisation, considering we're writing a draft constitution. I suppose that is more of a codification project than a reform one...

Voted coz of that magic gif.....so me....

Rest is tl,dr and boring mortal statistic

There was a survey about Conway a while ago.....

Stilpo can you send me a link about those results? I must have mised it...

you didn't miss it - it hasn't been published yet (sorry for the delay)

i was working on analyzing both of them this week but this one was more interesting to me though so i finished it first

the conway one should be coming in a few days

until then, you can see the preliminary results directly from the survey software company here: https://qtrial.qualtrics.com/CP/Report.php?RP=RP_aWrx80MoYIdvmXH

Where are names of participant of this survey?

Numbers means nothing if we don't know who voted what.

Conway is a known multi maker and he could/is easily manipulate survey.

Show us names behind numbers or this is legit as much as Conway's patriotism....as pile of shit

how secure is that survey. usually with some tools they dont bother even checking for duplicate ip's. if the survey opens on "open new tab" generally results can be easily manipulated.

Stilpo, don't give a single name to this loon.

If Stilpo deny names it will be clear his surveys are forged.

Just like your "referendum" Boru.....you Orcs simply can't do a sinlgle thing in honest way....so insecure wretched creatures..

Let me clear something up for you right now: I will NEVER publicize identifying information about people who have participated in my surveys. Not only did I give my word that participation would be anonymous, but making the promise in the first place is simply common sense. If peoples’ answers were public, they are vulnerable to harassment from the opposition about their participation and may not feel comfortable giving an honest response (or any response at all). This is in fact a very real concern that people have brought up in the past, and one that I must respect if I expect them to keep taking my polls.

As for your concerns of data tampering, I understand where you are coming from, but there are a few things you can do to be reasonably confident that I have not willfully forged the results. First, take a few minutes to familiarize yourself with the program I use. If you sign up for an account and explore the interface for yourself, you will find that it is virtually impossible to alter the data with this software. Unlike Google Docs, this program does NOT allow you to edit individual responses. The only thing that you can possibly do to alter data is delete or filter-out somebody’s ENTIRE answer set. But if you did either of these things, that person’s comments would not appear in the comments section and PEOPLE WOULD NOTCE that their comments are missing. Thus it is quite literally impossible for me to alter *existing* responses.

I do, however, share your concern about potential multis. In fact, it was one of the reasons I chose to use Qualtrics for my surveys in the first place. It collects metadata on things like IP address and OS/browser/flash versions that I can (and do) compare to ensure that the survey is not taken twice from the same computer. However, I admit that it would still be possible for a crafty multi to hit me from two different computers on two different networks. In such a case, it would be nearly impossible for me or anyone else to detect the multi unless they used the name of a dead citizen (which I check) or I cross-referenced the links with a list of suspected multi names (which I would be willing to start doing if somebody provided me with a list).

So why should you trust me to do this multi-hunting myself? Good question! In all honesty, I would WELCOME an extra pair of eyes from a mutually-trusted third party to help look over the data for multi issues (provided we were up-front about who it will be BEFORE people take the survey). In fact, THIS IS SOMETHING THAT I HAVE REQUESTED REPEATEDLY IN MY ARTICLES. Which begs the question: why have you and your friends repeatedly IGNORED these requests for help (especially the one for the July survey where I specifically asked for help from the anti-Conway camp to help oversee the Conway bonus section)?? And, after repeatedly ignoring these requests, what grounds could you possibly have of accusing me of misconduct?