THE JEWISH REVOLT AGAINST ROME: HISTORY, SOURCES AND PERSPECTIVES

•

by

•

by cirujanoo

THE JEWISH REVOLT AGAINST ROME:

HISTORY, SOURCES AND PERSPECTIVES

The pursuit of history involves asking questions about the past, which

is obviously no longer directly accessible. New data thus generates new

questions; however, old data may also attract new questions and new

perspectives. Thinking about history is to an important extent determined

by contemporary interests and circumstances. As these interests

and circumstances change, perspectives and the questions asked

change. Setting aside traditions and historical memories, what remains

of the ancient past are the contemporary sources that are available

to us: literary, documentary, numismatic, epigraphic, iconographic

and archaeological. However, these sources are not always simply or

directly available to us. Some have been handed down by tradition,

which is the case for most of the literary texts, while others have been

actively retrieved by modern exploration. What the extant sources

share is that they represent only a small part of all source material

that was once in existence. Nevertheless, the available sources are the

building blocks for scholarly study of the past. The study of each of

these sources entails its own methodological requirements, difficulties

and possibilities.

The challenge for ancient historians is to understand these sources

as distinct and separate but at the same time as part of a shared historical

context. Acknowledging the distinct nature of each kind of source

and an appropriate method and hermeneutics to approach each one,

the integral use of different sources is important because these reveal

different aspects of an ancient society. This does not mean that all

forms of evidence available to us should be related to each other in

order to achieve a single coherent reconstruction. To aim at such a

reconstruction would mean to ignore the fact that we have only fragments

of the whole. Nonetheless, ancient historians should not focus on only

one body of evidence but take all of it into account and assess whether

a particular piece provides an answer to the historical questions asked.

This volume brings together different disciplines, some for the first

time, and combines fields of research that should not be pursued in

isolation from each other should we wish to further our understanding

of the broader historical context of the first Jewish revolt against

Rome. Several issues with regard to the literary, archaeological,

numismatic and epigraphic sources and the historical reconstruction

of this conflict warrant further reflection. True to the pursuit of

history briefly outlined here, this volume presents new data that

generate new questions, as well as new perspectives that shed new

light on already familiar data. The perspectives offered by the various contributors are often interdisciplinary, engaging different sources

and approaches. Whether or not the war of the Jews against the Romans

was the greatest war that had ever occurred to that point, as Josephus

claims (B.J. 1.1), for ancient historians the Jewish revolt against Rome

in the first century c.e. provides the opportunity to study one of the bestdocumented provincial revolts in the early Roman Empire.

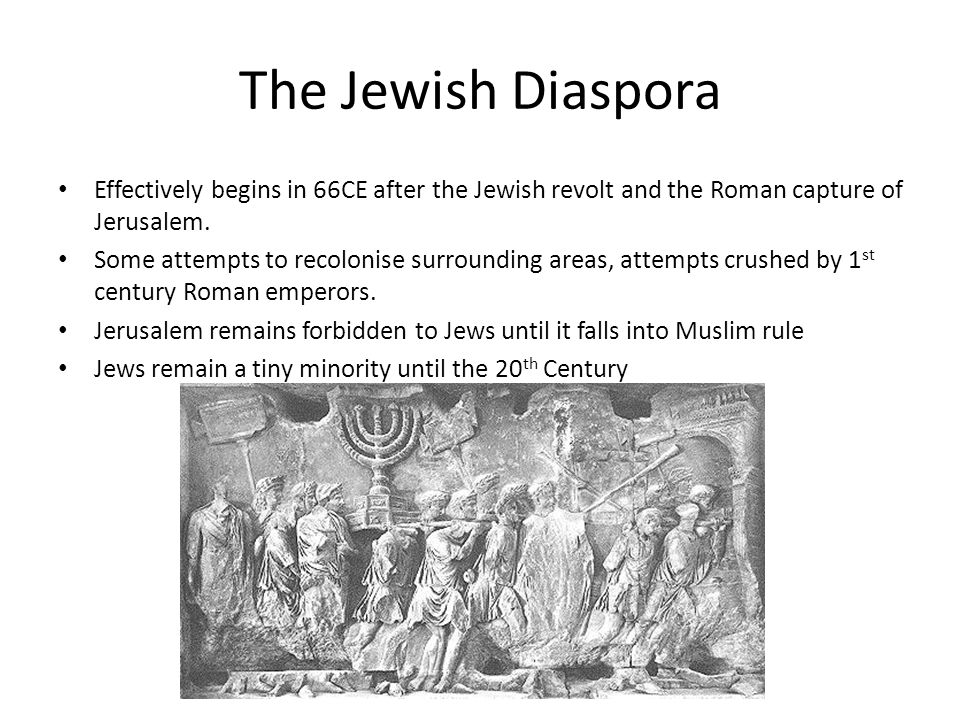

Firstly, there is the archaeological evidence. Sites that were destroyed

in the suppression of the revolt have been excavated. The well-known

examples are Jotapata, Gamla, Jerusalem and, of course, Masada. These

excavations dramatically illustrate the preparations, tactics and effects

of Roman sieges. Recently, evidence of subterranean hideouts has also

been unearthed, illustrating some of the preparations that were undertaken

by Jewish villagers.

Secondly, there is unique numismatic evidence. The Jewish rebels

asserted their independence from Rome by issuing their own coinage.

The epigraphy and iconography of these coins express the inauguration

of a new era under a Jewish authority.

Thirdly, there is documentary evidence. A reassessment of some of

the manuscripts from Murabbaʿat suggests these belong to the period of

the revolt. These documents also use dating formulas and phrases similar

to those on the revolt coins. The documentary evidence illustrates

that the independent government guaranteed the legal framework of

everyday transactions and that daily life went on during the revolt.

Finally, there is also the literary evidence. The accounts of the Jewish

aristocrat Flavius Josephus in particular provide a wealth of material

that stands out in comparison with the dearth of evidence available

about other revolts in the empire. For many if not most of the events,

Josephus is our only source of evidence. Recent discussion has again

focused on the advantages and disadvantages, possibilities and limitations

of Josephus as a source for modern historical enquiry into the

revolt. One of the fundamental issues is whether Josephus’ accounts

are proper historical sources for understanding pre-70 c.e. Judaea or

whether they are instead historical sources for understanding the

historical context of Josephus in Flavian Rome. Is it possible to reach

beyond Josephus’ narrative by distinguishing the different sources he

used, to obtain different perspectives on the events he reflects upon

and thus to move closer to “what really happened”? Or is Josephus’

narrative all we have and must we accept that we cannot discover what

really happened, as various historical scenarios may explain why

Josephus wrote what he wrote?

Taking into account all of these sources and being mindful of their

diverse nature we must ask: Which historical questions do they allow

us to answer and which not? It is up to us to think through the relationships

between the different sources, perspectives and historical

reconstructions. For example, in what respect do literary texts, considered

as “categories of thought,” and material remains, considered

as “categories of behaviour,”relate to each other? Are these categories

part of a shared context, remaining distinct yet possibly related elements?

This volume offers fascinating insights into some aspects of

the “prehistory” of the revolt. In this volume Andrea Berlin argues

that during the first century b.c.e. a shift in material culture can be

observed in certain villages in Galilee and Gaulanitis. She suggests that

this shift reflects a new emphatic expression of Jewish ethnic identity

and solidarity. Berlin argues that this was due to the impact of Rome

on the region from the middle of the first century b.c.e. onward. Brian

Schultz argues here that Pompey’s conquest of Jerusalem in 63 b.c.e.

decisively determined the interpretation of the so-called Kittim in

the War Scroll from Qumran. The Romans were perceived as the eschatological enemy, the defeat of which would inaugurate the messianic age.

We should not simply conflate these two bodies of evidence; one

being material and revealing behaviour, the other being literary and

revealing thought. The literary texts cannot be used to reconstruct

what Jewish villagers in Galilee and Gaulanitis thought during a

period in which the patterns of material culture changed. However,

when considering the impact of Rome on ancient Palestine and the

different responses it generated, these different sources do provide us

with evidence about how some behaved and what others thought in

light of the Roman presence. As such, they reveal the diverse range of

responses to the presence of Rome in the area. In this regard they are

distinct, yet all represent parts of a shared historical context.

1. The Roman Context

As several authors in this volume emphasize, the Jewish revolt against

Rome should be understood within a broader Roman context. Greg

Woolf and Werner Eck provide a Roman perspective on the occurrence

of provincial revolts and their perception and on the role played

by Roman representatives in Judaea.

In his article, Greg Woolf is concerned to map the difference between

normative explanations of revolt employed today and those used by

the ancients. Modern explanations are frequently schematic and leave

little space for ancient motivations. Ancient accounts by contrast

focus on the morality, motivations and agency of individuals.

Structural analysis, Woolf argues, may account quite well for the

social, geographical and chronological location of dissent, at least at

a very general level. However, such a perspective has more difficulty

explaining apparent anomalies such as the participation of the highly

integrated local elite, Jewish and Gallic aristocrats, former Roman

soldiers and client kings. Moreover, such structural analysis provides

little insight into how participants understood events at the time, as

we have almost no rebel voices.

As to a Roman understanding of provincial revolts, it is impossible

to know how Roman emperors perceived their causes, but we do have

access to what members of the Roman elite thought. However, this

does not involve accepting naive realist accounts of ancient authors.

Taking the example of Tacitus, Woolf makes an important observation

as to what kind of historical information Roman literary sources

may reveal: “Tacitus’ own reconstructions of revolts and their causes

can be taken to reflect the kind of explanation formed by members of

the imperial ruling classes when they considered individual revolts.”

However, this understanding will also have influenced how Roman

elites behaved and acted in the provinces: second-century governors

did not go out to their provinces with scrolls by Tacitus, Livy and Sallust

in their bags, but discussions of revolts by ancient historians must

have reflected and shaped their own actions in the provinces, as well as

the experience of their peers and readers: “Tacitus’ provinces did not

exist in an intertextual bubble, but needed to be constantly related to

the empire known by experience.”

Susan Mattern has drawn attention to the value of the testimony

of literary sources for understanding the reasoning and motivations

behind the type of decisions taken by emperors and the ruling elite.

Woolf’s position reflects a similar understanding of ancient literary

texts that acknowledges the formation of the ideas of the ruling

elites as being determined for the most part by literature and rhetoric,

and that therefore literary texts reflect the concerns and understandings

of these elites and, crucially, may also help us to understand

their actions.

I highlight this approach, since Steve Mason does not take this view

into account in his contribution to this volume when he argues that

even if we had the confidence to declare Josephus’ account of Titus’

war council about the Jerusalem temple a word-perfect transcript,

it would tell us little about Titus’ general views or those of his

commanders. This stretches the argument too far. Mason makes a valid point

that the real-life situation would have been much too complex and

evolving too rapidly for a literary representation to mirror that reality.

Different historical scenarios may explain why Josephus’ account is as

it is. There is no direct relationship between his story and real events,

such that it mirrors real events. However, to acknowledge that we cannot

know what really occurred, in a von Rankean sense as it were,

does not entail that we cannot know about anything other than the

particular context of the narrator. As Mattern and Woolf suggest, it is

precisely this context that may inform us not only about how Roman

elites perceived and imagined certain events but also how they acted

according to that perception. In this case, the “manufacturing of consent”

may be assumed to have conditioned the thoughts and behaviour

of the Roman elites formed by that knowledge.

Woolf’s contribution is important to the study of the Jewish revolt

against Rome as it demonstrates that at least for other parts of the

Roman Empire we are able to enquire after the understanding of

Roman elites with regard to provincial revolts. Actually, insofar as he

is writing for a Roman audience,9 Josephus may provide us with similar

access to Roman elite perspectives. As to the account of Titus’ war

council, I agree that it does not literally mirror reality, but similar to

Mattern’s argument concerning Herodian’s report of Commodus’ war

council, I suggest that Josephus’ report, in a more general sense, may

reveal patterns of thought among Titus and his commanders. Whether

they changed their minds, revealed their real thoughts or were not in

complete control of everything that happened does not a priori render

Josephus’ report meaningless for that historical context. The “historicity”

of such a war council can be understood in different ways. How

Josephus imagined the conversation between Titus and his commanders

might reveal significant elements that indicate Roman concerns and in

turn might suggest Roman actions. However, this would need to be explored further. Werner Eck reflects on Josephus’ position within the Roman context

and what that means for the various perspectives taken in his

accounts; Josephus was not an impartial observer of and writer about

the revolt, not only with regard to the Jewish groups involved but

also with regard to the perspectives he provides on the Roman prefects

and governors. He could not be overly critical of Rome, as the

emperor and his family represented Rome. Therefore, Josephus targeted

his criticism at the Roman representatives in Judaea, and not

at all of them, but the prefects specifically. Surprisingly, Eck notes,

Josephus never criticizes the legates he mentions, except for the senator

Vibius Marsus. However, based on our knowledge of how the

Roman Empire functioned administratively, Eck points out that it was

not the prefects criticized by Josephus who were responsible for what

went on in Judaea until 66 c.e. but rather the legates/governors of the

province of Syria. Furthermore, there was a significant difference in

social status between these two types of functionaries, something readily

understood by Josephus’ Roman audience. The legates of senatorial

status would have been people on whom Josephus would still have

been dependent after 70 c.e. This would explain why he did not aim

his criticism at them.

Rather than assessing certain actions taken by the prefects as provocations,

Eck explains these as perfectly in line with normal Roman

customs, and he stresses that the Roman response to unrest caused by

these actions was in general sensitive and balance

😛“Das konnte aus

jüdischer Sicht durchaus provozierend sein, doch ist damit noch nicht

einfachhin in allen Fällen auch das Motiv der Präfekten identifiziert.”

Eck thus also argues for a perspective that understands the behaviour

and actions that Josephus ascribed to Roman representatives in

Judaea within the context of how Romans would have understood and

expected their prefects, procurators and governors to behave in the

provinces.

2. The Revolt’s “Prehistory” and the Motivation

of Jewish Rebels

The notion of a prehistory to the revolt may conjure up the idea of a

longue durée perspective taking into account a multiplicity of longterm,

rather than immediate causes that contributed to the revolt,

including social, economic, demographic and political events.

From such a structural mode of analysis, Jewish responses to

“Romanization” may present themselves as an interesting element that

warrants further study. This does not imply that we should see the

Jewish revolt against Rome in essentialist terms as a monolithic conflict

between Roman and Jewish culture, as if there was something intrinsic

in Jewish and Roman society that made coexistence between the two

impossible. Nor should we assume without further qualification that

responses from the first century b.c.e. to some of the actions of Rome’s

representatives in the area were simply transmitted in unaltered form

for decades and that we can ascribe these to those who revolted against

Rome. Bearing these caveats in mind, some fascinating responses to

the impact of Rome are revealed in the contributions by Andrea Berlin

and Brian Schultz.

As noted above, Andrea Berlin detects a shift in material culture in

Galilee and Gaulanitis that indicates a development from a gradual

to a complete division between Jews and non-Jews as far as aspects

of daily life are concerned (pottery, miqvaʾot and synagogues). In the

early first century b.c.e., differences in shopping and dining habits and

some indicators of ethnic identity can be observed, but they are not yet

wholly divided spheres: “Market routes still connect areas where different

peoples live, and the places where they gather to petition or honor

their deities remain the old, now somewhat out-of-the-way sites.”

However, a few generations later, around 10 c.e., in the early years

of Herod Antipas and Herod Philip, all this had change

😛“Those few

commonalities and connections no longer exist. Galilean Jews . . . now

shop exclusively in their local markets. They stock their pantry shelves

only with saucers, bowls, and kitchen vessels made nearby. They no

longer buy red-slipped dishes from Phoenician suppliers nor do they

light their homes with mold-made lamps.”

Why does this happen? Berlin suggests that a new development gave

rise to this new assertion of Jewish identity: the impact of Rome on the

region, specifically in the form of shrines that honoured Roman deities.

The Jewish response was to close ranks, further developing their

separate and distinct lifestyle. Berlin suggests that cultural differences

hardened into cultural divisions that caused Galilean and Gaulanite

Jews to perceive the world around them as different from their now

sharply delineated milieu. Such a perception may have contributed

several decades later to tensions between Jews and non-Jews leading

up to the revolt, although it is difficult to prove such a causal, longterm

development.

The Dead Sea Scrolls are virtually the only contemporary documents

we possess from pre-revolt Judaea. These manuscripts put us

in an exceptional position to assess the ideas, expectations and selfunderstanding that were conceived, articulated and disseminated

among a specific Jewish group involved in the conflict. In what way

were ideas about an anticipated eschatological war, as in the War Texts

from Qumran, related to Rome’s impact on Judaea and can we determine

whether such ideas had any bearing on the events of 66 c.e.

and afterwards?

Brian Schultz focuses on the War Texts from Qumran, most notably

the War Scroll from Cave 1. He presents his thesis on the composition

history of the War Scroll and on the shifting interpretations

of the Kittim as the eschatological enemy. As noted above, Schultz

argues that the final identification of the Kittim, from the Seleucids

to the Romans, was determined by Pompey’s conquest of Jerusalem

in 63 b.c.e. The belief that the defeat of the Kittim would inaugurate

the messianic age suffered a mortal blow with Pompey’s conquest, as

independence from the Seleucids had not heralded the messianic age.

Schultz suggests that “both the ones spurring on the revolt as well as

the authors of the various War Texts had as a goal Judea’s political and

religious independence from foreign interference. Just this commonality

alone highlights the possibility that eschatological factors may have

motivated at least some who joined in the conflict.”

Although James McLaren argues against using distinctive factors

such as religious ideas or extremist ideologies to explain why Jews

revolted against Rome, his analysis highlights an aspect that is also

noted by Schultz: the claim that the land was to be purged of foreigners

and free of foreign rule.16 One should be careful not to lump this

evidence presented by McLaren and Schultz together based on a presumed

similarity of ideas. Nonetheless, here too Josephus’ framework

must not predetermine the manner in which we understand evidence

from pre-revolt documents such as the Dead Sea Scrolls. Qualifications

such as extremist or sectarian are less valuable to an understanding

of what is at stake in literary texts such as the Qumran manuscripts.

More interesting is that a text such as the War Scroll also reveals the

same view on the purpose of war: to be free of foreign rule. Whether

this is significant remains to be seen. In terms of the long-term

development of ideas that may have motivated those who revolted,

it is at least suggestive enough to warrant further investigation.

McLaren focuses on two sources of information: Josephus, writing

soon after the revolt, and material remains in the form of revolt coins

and manuscripts from Murabbaʿat with dating formulas, both dating

to the time of the revolt. What do these sources reveal about the

motivation of those who revolted? McLaren’s methodological point

of departure with regard to Josephus is to read Josephus against himself:

“Where Josephus makes accusations about the rebels, especially in

terms of what they proclaimed to be doing, it is highly likely that the

rebels were using that issue as a motive for the war.” He argues that

Josephus’ “extensive use of ‘freedom’ in relation to why the war was

being fought warrants recognition as the primary motive.” Together

with a review of the actions Josephus ascribes to those who revolted

against Rome, McLaren infers an active engagement with the Romans

in Judaea aimed at getting rid of them, as well as the rebels’ aim of a

new state: “This was not a protest that had got out of control; it had

been a choice to undertake a war of liberation.”

As to the documentary evidence from Murabbaʿat, McLaren argues

that the dating formula and the Hebrew language in which some of

the documents were written signals the existence of a new state. He

also argues that the documents are clear evidence that life went on

even once the war had commence

😛“Irrespective of what the owners

of the documents believed, the existence of the new formula is

extremely significant. If part of an official formula it means the people

charged with its operation were concerned to put in place procedures

that clearly declared a new era had commenced. If done because it was

simply common practice then it indicates a widespread acceptance of

the new era.”

As to the numismatic evidence, McLaren emphasizes that the people

who minted the revolt coins must have been supporters of the war.

Moreover, if more people were responsible for different issues of revolt

coins, then the greater the number of Jews in Jerusalem who were

openly committed to the revolt. Unlike Robert Deutsch and Donald

Ariel (see below), McLaren aims to understand this material independent

from the framework of Josephus’ narrative. He, therefore, does

not suggest specific identifications of those responsible for minting

the revolt coins. Nonetheless, in a general sense, the documentary and

numismatic evidence independently corroborates an aspect of Josephus’

account when “read against Josephus.”

Viewing the material evidence together with Josephus, McLaren

notes the coherence regarding the purpose of the war: once again, to

be free of foreign rule. However, there are also important differences.

In Josephus, “[t]here is little sense of an independent state being established

and certainly no mention of its name, ‘Israel,’ let alone reference

to ‘Zion.’ ” As such, the documents from Murabbaʿat and the revolt

coins constitute independent evidence that sheds important light on

the motivation of the Jews who revolted against Rome and the message

that they wished to convey.

3. Flavius Josephus

Of necessity, modern enquiries into the history of the Jewish revolt

are for the most part dependent on Josephus. Of course, there are

other sources that corroborate that the Romans suppressed a revolt in

Judaea sometime in the second half of the first century c.e. Archaeological

excavations have unearthed sites, towns and villages that were

besieged and destroyed, as was the city of Jerusalem. Roman imperial

propaganda such as the Judaea Capta coins and the arch of Titus

display a message of Jewish submission and Roman victory. In addition

to Josephus, other literary sources also make clear that the Jerusalem

temple was destroyed, and also that different Jewish factions

fought each other before they united against the Roman legions which

appeared before the walls of Jerusalem. Tacitus provides a breakdown

of the different forces within the city and the different areas they

controlled (Hist. 5.12.2–4). He, or his source, thus corroborate in a general

sense part of Josephus’ account. However, when it comes to specific

events, causes and developments, and people and their thoughts and

actions, Josephus is our only source.

In this volume the various contributors take different positions with

regard to the use of Josephus as an historical source for pre-revolt and

revolt Judaea, with some contributors being more pronounced than

others in their methodological considerations. Put simply, the parameters

of the discussion revolve around the question of whether Josephus

is a source of evidence at all for the matters that he narrates or

rather a source for the contemporary context in Flavian Rome. Some

contributors to this volume remain suspicious of Josephus, arguing

that Josephus can be read against himself as well as in light of other

non-literary sources (James McLaren), critically as well as in light of

other literary sources (Julia Wilker), or between the lines along with a

comparison of parallel accounts to determine Josephus’ own voice (Jan

Willem van Henten). Others focus on a literary comparison of Josephus’

parallel accounts to consider what sources Josephus had available

and how his views changed between his writing of the War and

the Antiquities (Daniel Schwartz).

In his contribution to this volume, Steve Mason’s general thesis

is “that the different views of history held by those of us who study

Roman Judaea is a sizable but mostly neglected problem.” Mason’s point

is not so much that Josephus does not potentially reflect events

of the revolt and before, but that in the absence of other evidence,

literary or otherwise, there is no opportunity for the historian to

corroborate or falsify the specifics of the events that Josephus narrates. Especially difficult is Josephus being the sole source of evidence for

people’s thoughts and motives, as Mason’s view of history is based on

Robin G. Collingwood’s philosophy of history, which perhaps most

controversially states that thoughts and intentions behind actions in

the past are the core interest of historical inquiry. Mason, therefore,

emphasizes imagining the motives of those who acted in the past in his view of history. However, he also asks how any one source can be taken as a truthful reflection of people’s motives, especially since reallife situations affect people’s motives and actions. In addition, the many people and factors involved makes it difficult to draw a simple causal line from intentions to actions and results, especially for ancient history when we do not have the wealth of evidence of modern history.

Therefore, the methodological point of departure cannot be dependent

on any one source. Rather, Mason argues that a defensible historical

method begins by asking historical questions, thinking through

different scenarios and assessing the different sources on their own

merits, and then determines whether they can or cannot help answer

our questions. If they cannot, it does not render a source unreliable or

implausible, qualifications that according to Mason are meaningless in

terms of historical method. Mason therefore takes an agnostic point of

view when it comes to much of the history of the revolt: “[A] wide

range of possible underlying events might have happened that would

still allow us to understand how Josephus produced his story.” Mason

illustrates his approach by considering two important episodes in the

revolt: the campaign of Cestius Gallus in 66 c.e. and the role of Titus

in the destruction of the Jerusalem temple. In both cases Mason is

clear about his aim: to understand the motives of Cestius Gallus and

Titus. In this respect Josephus as a source is not considered unreliable

but rather unhelpful, for which, however, he is not to be faulte

😛

“[H]istorical method cannot change because we have the extraordinarily

elaborate accounts of Josephus for first-century Judaea. We are

in the same logical predicament as those who study the Josephusless

provinces.”

Other scholars take a different approach, not so explicitly concerned

with their views on the aim of history, but more with their approach to

Josephus. This reveals a fundamental difference in their point of view;

focusing primarily on one literary source, Josephus, the contention is

that historical information can be drawn from it primarily by means

of literary analysis—historical information, that is, which predates

Josephus’ Flavian context. The three following contributions focus on

Josephus’ portrayal of various figures: the Herodians, Herod the Great

and Archelaus (van Henten); Agrippa II and Berenice (Wilker); and

the Roman procurator Lucceius Albinus (Schwartz). How How and what

kind of historical information is taken from Josephus?

Jan Willem van Henten suggests that a literary analysis of three

themes helps to articulate Josephus’ own voice in his interpretation of

the events in the War and the Antiquities: (1) conflicts (stasis) within

the royal family under Herod and Archelaus, (2) the references to rebellion

during both reigns, and (3) Josephus’ characterization of both rulers.

Such an analysis may help determine the plausibility of Josephus’

presentation of rebellion under Herod and Archelaus. Comparing the

accounts in the War and the Antiquities, van Henten argues that Josephus

is tendentious in his presentation of certain events, especially

with regard to Herod. As Josephus’ depiction of Archelaus in both

works is basically the same and consistent, van Henten suggests that

Josephus’ criticism of him seems much more justified than in the case

of Herod. With Herod things are different. Van Henten argues that

there is not much evidence for large-scale rebellion or internal family

strife under Herod, or of Herod being a tyrant. Rather, “Josephus may

have re-crafted Herod’s picture in a few passages in the War, but much

more extensively in the Antiquities, to adjust it better to his basic

message about the prehistory of the war against Rome. If this conclusion

is justified, it may mean that he has projected the negative image of

Archelaus and the bandit leaders Menahem and Simon bar Giora as

tyrants retroactively onto Herod.”

Julia Wilker argues that Agrippa II more or less deliberately decided

to join the Roman side in this conflict and fought alongside the imperial

troops until the end of the war. She reads Josephus critically and

in light of other literary sources and suggests that in the War his portrayal

of King Agrippa’s participation in the Jewish war, in terms of

his actions and responsibilities, differs significantly from what we can

reconstruct as being his real role during the conflict and the succeeding

campaign: a pious Jew sympathetic towards his fellow countrymen,

although his loyalty to Rome was never in doubt, who acted as

a mediator, attempting to persuade the rebels to surrender. Wilker

argues that this portrayal of Agrippa II in Josephus’ War was not so

much determined by Josephus being dependent on Agrippa in Rome

after the revolt, but rather that it was influenced by Josephus’

selfportrayal regarding the time after his surrender at Jotapata.

Josephus’ portrayal of Agrippa II and his actions drive home the

point that “[t]he Herodians as depicted in the War could therefore

neither be blamed nor criticized for what happened in the province.”

Wilker suggests that from a Roman perspective this would make

Agrippa suitable to be included in the reorganization of the province.

She argues that Josephus had Herodian interest and self-perception in

mind while writing his work. From this she concludes that Agrippa II

aimed to gain power and influence in post-revolt Judaea, but this

effort obviously failed. Josephus’ portrayal of Agrippa II and Berenice

in the Antiquities is rather different and much more critical than in

the War.

In his contribution to this volume, Daniel Schwartz sets out to compare

Josephus’ parallel accounts of Albinus, considering what sources

Josephus had available and how his views changed between his writing

of the War and the Antiquities. Schwartz argues that Josephus is

quite consistent in his positive approach to Albinus in the Antiquities

(20.197–215), using him as a foil for Jewish villains: they are the ones

responsible for the revolt that is about to break out. However, there

is one negative passage about Albinus in the section concerned—A.J.

20.215. Schwartz suggests two possible explanations: that Albinus’

actions should actually be understood from a positive perspective, as

he was doing what a responsible procurator should do, or that Albinus

accepted bribes to release prisoners. Schwartz notes that this latter

perspective, out of tune (“remarkably self-contradictory in tone”) with

the narrative in the Antiquities, is also found in the parallel narrative

in B.J. 2.272–276.

The negative perspective on Albinus in the War, argues Schwartz,

fits Josephus’ message very well. The situation was similar to a rollercoaster

out of control. At the same time, there is a contradiction in

Josephus’ views on the matter. In the War he suggests that had Rome

sent better procurators and Jewish leaders kept their own hotheads in

check the ensuing revolt would not have been inevitable. About twenty

years later, in the Antiquities, Josephus’ message has change

😛“t was

no longer important for him to urge the Romans to send better governors.”

More importantly, in the Antiquities Josephus lays full blame

on Jewish actors, notably members of the elite. What had happened

between the account in the War and that in the Antiquities was that

Josephus brought his explanation in line with Jewish historiography

and theodicy: What had beset the Jews was due to their own sins.

As to Josephus’ manner of writing, Schwartz notes that the negative

perspective on Albinus was unintentionally retained in the Antiquities

as a rhetorical mouthpiece, in this case betraying both the influence of

the parallel account in the War and a common source.

Actually, Schwartz’s approach seems here in accord with Mason’s

methodological requirement that Josephus’ accounts are first studied

on their own merits. The historical information drawn from a comparative-

literary analysis pertains to Josephus’ context between his writing

of the War and the Antiquities, not to the revolt or its prehistory as

such. The contributions by van Henten and Wilker likewise demonstrate

similar shifts in Josephus’ perspective on figures and affairs in

pre-revolt and revolt Judaea, but in addition they make claims concerning

those historical contexts and not only that of Josephus in Flavian Rome.

4. Josephus on the Fourth Philosophy, the Sicarii

and Masada

The following three contributions are also largely concerned with Josephus,

but from different disciplinary perspectives. Pieter van der Horst

takes a philological approach to Josephus’ characterization of the

fourth philosophy as a philosophia epeisaktos. Uriel Rappaport, understanding

the fourth philosophy and the Sicarii to have been the same movement, takes a historical approach and reviews the movement’s history and several of its features on the basis of Josephus’ accounts. Jodi Magness takes an archaeological approach to the Roman siege of Masada, arguing that the material evidence supports Josephus’ account of the siege.

Pieter van der Horst argues that Josephus used the characterization

philosophia epeisaktos for the fourth philosophy in A.J. 18.9 to emphasize

that, unlike the three other philosophies (Pharisees, Sadducees,

Essenes), this one had characteristics that were intrinsically un-Jewish

and alien to the Jewish tradition. Using this phrase, Josephus refers to

the movement’s innovation and reform in ancestral traditions: freedom

from foreign domination. Van der Horst argues that the innovative

element was not paying taxes to the Romans, whereas in previous centuries

Jews had done so to the Assyrians, the Babylonians, the Persians

and the Greeks: “The zeal for independence that the adherents of the

fourth philosophy conceived as a duty to God was seen by Josephus

and others as rebellion against God.” However, in light of Schultz’s discussion of the War Scroll and McLaren’s discussion of Josephus,

the Murabbaʿat documents and the revolt coins, one wonders whether

Josephus’ perspective was more informed by hindsight and his own

context than by knowledge of the historical circumstances. The zeal for

independence may have been more widespread and not only confined

to one particular group.

In his contribution to this volume, Uriel Rappaport understands

the fourth philosophy to be the same as that later referred to as the

Sicarii (“fourth philosophy” was the name given by Josephus, “Sicarii”

that given either by the Romans or Josephus). When reviewing the

group’s history, being of exceptionally long duration (approximately

63 b.c.e.–117 c.e., or perhaps even to 135 c.e.), Rappaport makes his

view on Josephus’ relationship to this group and how it influenced

his portrayal of the Sicarii very clear. First, Josephus would have been

antagonistic to the Sicarii, but not in the same personal way he was

in relation to John of Gischala. Second, when Rappaport mentions

the Sicarii’s capacity for enduring torture, he admits this may simply

be a stereotype, but he adds that on the other hand that would

not imply that it was not true: “t may point to one of the personal

deficiencies and an inferiority complex of Josephus concerning personal

courage.”

In an additional note appended to his contribution, Rappaport

responds to van der Horst’s suggestion that the zeal for liberty of the

fourth philosophy, which resulted in opposition to paying taxes, was

un-Jewish. Rappaport understands this characterization by Josephus

as a criticism of the Maccabees, who exemplified several of the features

also exhibited by the fourth philosophy.

In her contribution to this volume, Jodi Magness re-evaluates Josephus’

narrative about Masada in light of the archaeological evidence,

focusing on his account of the Roman siege and concluding that the

material evidence supports Josephus’ account of the siege. Magness

looks at the logistics of the siege and evidence for the siege itself. She

argues that Josephus’ description is consistent with the remains at

Masada, where eight camps (A-H) and a circumvallation wall with

watchtowers still encircle the base of the mountain. Also, Josephus

accurately describes the location of Flavius Silva’s camp (F). As to

the pottery remains, what the Roman soldiers ate and how provisions

were supplied, Josephus makes no reference to these matters. Here,

archaeology provides important new insights into the different aspects

of the Roman siege of Masada. Magness argues that the predominance of

locally produced bag-shaped storage jars in Camp F can be understood

in light of the supply logistics. Fresh water had to be brought to

Masada from Ein Aneva but mostly from places farther away such as

Ein Gedi, Jericho and Ein Boqeq. Unlike pottery from the legionary

kiln works in Jerusalem, which are characteristic Roman types apparently

manufactured by military potters, the bag-shaped storage jars

and local cooking pots from Camp F at Masada are Judaean types.

Magness suggests that these were manufactured by Jewish potters at

Ein Gedi, Jericho and perhaps Ein Boqeq and transported by boat

to Masada.

Discussing the evidence for the siege itself, Magness considers the

existence of an iron arrowhead workshop, catapults and ballistae, and

the siege ramp. According to Magness, Josephus’ report that Eleazar

and the Sicarii found raw metals that had been stockpiled by Herod

is supported indirectly by archaeological evidence. She argues that the

material evidence in loci 442 and 456 suggests that these rooms served

as workshops (fabricae) for the forging of iron arrowheads during the

time of the revolt. In light of the absence of iron projectile points at

Masada, Magness, together with Guy Stiebel, had previously proposed

that catapults were not employed during the siege, which contradicts

Josephus’ account. In this contribution, however, Magness argues that

the archaeological evidence can be reconciled with Josephus’ narrative.

Following Gwyn Davies, Magness believes they must have been

used but the Romans afterwards collected and recycled them. Finally,

Magness rejects the claim by Benny Arubas and Haim Goldfus that the

siege of Masada was not seen through to the end and that the siege

ramp was not operational.

5. The Jewish Revolt Coins

Considering the sources available for historical enquiry into the Jewish

revolt, the coins minted by the rebels are first-hand evidence as to the

commitment of those supporting the revolt. This volume contains two

contributions from a numismatic perspective that shed important new

light on various features of the revolt coins.

In his contribution to this volume, Robert Deutsch considers the

iconography, the minting authority and the metallurgy of the revolt

coins. Discussing the cultic iconography of the silver revolt coins, he

identifies the staff with three pomegranate buds as that of the high priest. Following Yaʿakov Meshorer, Deutsch identifies the chalice as

one of the two golden chalices depicted with other cultic vessels from

the temple on the arch of Titus.

The iconography provides important clues as to the minting authority.

The only straightforward symbol seems to be the staff, signifying

high-priestly authority. This may symbolize the minting authority:

either the priesthood or the temple institution. The consistent iconography,

epigraphy and denominations and the metallurgic similarity of

the silver coins throughout the five years demonstrate that the same

minting authority produced them. Deutsch agrees with others that

the source of the silver was the temple treasury and that the priesthood

was the minting authority. On the basis of a single “year one”

prutah, Deutsch also considers that the bronze prutot were minted by

the same minting authority. However, he agrees that the “year four”

bronze coins exhibit such significant changes (in epigraphy, the terms

of the inscriptions and new denominations) that these must point to

a different minting authority. Here, like Ariel, Deutsch relies on Josephus’

account of the different factions in Jerusalem to suggest that the

“year four” coins were issued by Simon bar Giora, as first suggested

by Baruch Kanael and supported by others. Deutsch also points to

another minting authority that was briefly active during the revolt,

that of Gamla, which produced a limited number of bronze copies of

the Jerusalem silver coins.

The final part of Deutsch’s paper is devoted to the results of a

metallurgic analysis of the silver coins, a neglected element

thus far. The high content of 98 percent silver, without

any significant deviation during the five years of the revolt,

may indicate that internal and external pressures did not affect

the high standards of the minting and the quality of the coins,

despite the decrease in the number of coins minted in the last

two years of the revolt.

Donald Ariel begins his contribution with a consideration of six

numismatic categories: iconography, the terms used in the inscriptions,

dating conventions, epigraphy, denominations and technology. From

this survey he concludes that the revolt coins (silver coins dated year

one to five, “year two” and “year three” bronze coins called prutot and

the “year four” bronze coins in three larger denominations) exhibit a

significant degree of heterogeneity in their numismatic features: “This

hints that the three groups were minted in different places and/or by

different people.”

Considering who minted the revolt coins and where, Ariel distinguishes

between the silver and the bronze coins. As to the place of the

minting of the silver coins, Ariel suggests that the most logical place

was within the temple precinct: the monumental stoa at its southern

edge, where economic and judicial functions were concentrated. As

to who was responsible, Ariel is more circumspect than Deutsch in

identifying the priesthood as the ultimate minting authority, arguing

that the minting authority may have been the priesthood, but that it

operated under or at least in coordination with those rebels who were

in command of the temple at the time: “Probably the same priests were

responsible for the minting even though the ‘minting authority’ had

changed three times. This is the reason for the stability of the silver

issues of the first Jewish revolt. The changing rebel leaderships did

not intervene.”

With regard to the bronze revolt coins, Ariel argues against Rappaport’s

thesis that both “year two” and “year three” prutot and the

“year four” bronzes were minted by Simon bar Giora. The prutot, for example,

date to a time when, according to Josephus, Simon bar Giora

was not in control of the city. Rappaport’s solution, that Simon minted

these coins outside the city of Jerusalem, is forced. Travelling mints

were mostly used for precious metal issues and, based on Deutsch’s

research, the distribution of the “year two” and “year three” coins does

not support their having been struck outside Jerusalem. Rather than

agreeing that Simon bar Giora was responsible for all bronze issues,

Ariel argues that the changes in iconography and denomination on the

coins from year three to year four suggest different minting authorities

for the two groups. Ariel suggests that the minting of Jerusalem’s

coins during the first revolt took place in separate locations and that

the bronze coins were struck in the area of today’s citadel in Jerusalem.

With regard to the exact identification of minting authorities for

the three revolt coin types, Ariel and Deutsch agree on “year four”

bronze coins having been issued by Simon bar Giora. They disagree

on the prutot, which Deutsch understands to have been minted by the

same minting authority as the silver coins, namely the temple priesthood,

whereas Ariel distinguishes two minting authorities, the silver

coins having been minted at the stoa in the temple precincts under

the authority of the priesthood (but with the ultimate authority of one

of the rebel factions during the five years) and the bronze coins having

been minted at another location—the citadel. Ariel ascribes these

bronze prutot to John of Gischala and the Zealots.

Deutsch and Ariel rely on Josephus’ accounts of who was in control

at various times and over which parts of the city of Jerusalem for

the exact identification of the minting authorities (cf. also, in more

general terms, Tacitus, Hist. 5.12.2–4). Whether or not one agrees

with the specific identifications, the numismatic analyses by Deutsch

and Ariel add important data to McLaren’s suggestions, as they differentiate

between different minting authorities and different locations.

This demonstrates, independently from Josephus, broadly based

support for the revolt against Rome. How broad the public support

was for this revolt cannot be exactly determined, but it is clear that

important members of the Jerusalem elite were involved. Nonetheless,

the Murabbaʿat documents may, as McLaren suggests, signify a more

widespread acceptance among the public of the new era inaugurated

by the revolt. In terms of method then, the numismatic perspectives of

McLaren, Deutsch and Ariel demonstrate what kind of historical

data can be inferred from the Jewish revolt coins, independently of

Josephus’ accounts.

6. Jewish and Christian Perspectives from Epigraphy and the New Testament

The final two contributions to this volume offer perspectives from

sources that are not used very often by historians of the first revolt.

Jonathan Price presents Jewish epigraphic evidence from Jerusalem

to enquire into aspects of Jewish life before and immediately after

the revolt. George van Kooten presents a case for the dating of three

Christian texts contemporary to the revolt and considers how these

texts perceive the revolt in the broader Roman context, especially

focusing on the figure of Nero.

Jonathan Price focuses primarily on one particular source: inscriptions

by Jews from first-century c.e. Jerusalem. Most of these texts

come from funerary contexts; however, some of the non-funerary

Jewish inscriptions have caused the most controversy. These are the

inscribed texts of various kinds, found near the walls of the Temple

Mount, many of which were thrown there during the systematic

destruction by the Romans in 70 c.e. Price points out that most of

them are intelligible only by reference to literary sources. However, the

Greek donation text and the Theodotos inscription add information

(about the financing of the temple through smaller contributions by

private citizens) and invalidate historical conclusions based on literary

sources alone (the first-century date of a synagogue in Jerusalem

for foreign Jews visiting the city). The donation and the Theodotos

inscriptions supplement the evidence, both literary and epigraphic, for

large numbers of visitors and established communities of foreign Jews

in Jerusalem before the destruction.

Jewish funerary inscriptions and practices in Jerusalem reveal the

impact of the Roman destruction on the Jewish population, with secondary

burial coming to an abrupt, almost complete halt. Price admits

that “in no instance can the unfinished state of a cave or ossuary, or

the presence of unburied bones, be definitely attributed to the war,

but surely the signs of haste and incompletion in so many of the caves

are the product of both the high mortality rate and the disruption in

routine caused by the Roman siege.” Nonetheless, in a few instances,

families were able to lay out their dead in caves after 70 c.e. and

return to put the bones in ossuaries. Price doubts whether these

families lived in Jerusalem: “The presence of the Tenth Legion in the

ruins of the city would have been a deterrent to Jews returning to

live there.”

Finally, Price points to recent archaeological, rather than epigraphic

evidence that sheds important new light on the Jewish population of

Jerusalem between the two revolts. Salvage excavations in Shuʿafat,

about 4 km north of the Old City of Jerusalem revealed the remains of

a settlement that was founded after 70 c.e. and abandoned and partly

destroyed, at the latest, in the first or second year of the Bar Kokhba

revolt. The excavators interpreted the site as a prosperous Jewish

settlement just 4 km north of Jerusalem, established in the last year

or two of the revolt or immediately afterwards, which must have had

the approval of the Roman authorities. Price refers to Josephus’ account

of Titus treating Jewish prisoners of higher social standing with special

consideration and argues that this settlement fits the description of

Givʿat Shaul, mentioned by Josephus.

In his contribution to this volume George van Kooten argues that

Christian sources such as 2 Thessalonians, Revelation and Mark are

contemporary to the events of the year of the four emperors and that

these Christian texts perceive the Jewish revolt within the larger context

of Roman politics at the time. More specifically, these Christian

sources exhibit a fear of Nero’s imminent return from the east. This

fear was due to the events regarding the great fire in Rome in 64 c.e.,

when Nero blamed the Christians, leading to their persecution. Van

Kooten argues that Jews were not similarly fearful of Nero because

they did not experience anything like this under his rule. Nonetheless,

he adduces Jewish sources such as book 4 of the Sybilline Oracles and

Josephus, as well as Roman sources such as Tacitus and the Templum

Pacis in Rome, to argue that these also perceive of the Jewish revolt in

its contemporary setting of Rome’s civil war and Nero’s death. Thus,

the New Testament texts that van Kooten adduces demonstrate the

earliest Christian reflections, contemporary to Josephus, upon the Jewish

revolt against Rome.

7. Concluding Remarks

What unites the contributions in this volume is obviously not one

view of the revolt’s history. In fact, the contributions reveal different

views even concerning what history is. Nevertheless, while there are

differences with regard to historical approaches and explanations, various

contributions also exhibit consensus on various issues. The focus

of this collection is on historiographical and methodological reflections

on our sources, their nature and the sort of historical questions

they allow us to answer. All of these issues are fraught with conceptual

and methodological difficulties and are not self-evident. Some contributors

reflect more consciously on the historical method, while others

illustrate their historical method through a concrete engagement with

the different sources. Some contributors put historical questions at the

forefront, while others provide a closer analysis of their sources, from

which they infer historical knowledge. What then unites the articles in

this collection is the sustained effort made to study the Jewish revolt,

using various perspectives and approaches that may inform as well as

challenge one another. In this regard, this volume aims to open up and

stimulate new avenues of interdisciplinary study of the revolt against

Rome in first-century c.e. Judaea. It might not be the greatest war

ever fought, but it certainly warrants sustained investigation, if only

because of its afterlife.

Youtube video link about Jewish Revolt Against Rome

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GTxDcif-XT4&feature=youtu.be&t=17

THE JEWISH REVOLT AGAINST ROME:

HISTORY, SOURCES AND PERSPECTIVES

by Mladen Popović

Jewish Revolt against Rome

The Jewish Revolt Researchment by Mladen Popović in academia.edu

Comments

I have not finished reading it but very detailed and informative.

Thanks my turkish brother EmparioZ

"Jerusalem remains forbidden to Jews until it falls into Muslim rule" - That ignores the period of shifting power between Byzantine and Persian rules.

When the wave of Jewish immigration to Ottoman Palestine began in 1882, some Jewish immigrants banned migration to Zionist thought and political goals in Palestine, the Ottoman government to Palestine. However, despite the Ottoman bans, there was a Zionist entity in Palestine.

Ottoman Emperor Abdulhamit and his immediate surroundings Starting with Herzl in 1896, they spoke intermittently for six years, and on May 19, 1901 the founder of Zionism was invited to the sultan and met with the Sultan ... Theodor Herzl, the founder of Zionism, wanted land from Palestine from the Sultan Abdulhamit for the state of Israel,

Abdülhamit is known to pay for the establishment of Israel, the land demand for the price of the Sultan and the Sultan.

The establishment of the state of Israel, which was blocked by Abdulhamit, then Israel foundation proposed to the Republic of Turkey in 1936, but found no support. The State of Israel, which could be established in 1901, was finally established in 1948.

Preventing a nation to establish their own state, does not fit human rights.

v