What Part of No Don't People Understand?

•

by

•

by Arjay Phoenician

Many Americans probably remember the big ballyhoo I made in early December, when the Jewitt administration declared war on Japan and invaded Kyushu. I had a lot of criticism for former President Jewitt, but this particular gripe of mine had a very simple logic to it, one that even Emerick the Great couldn’t comprehend when he and I had an IRC public discussion on the matter:

No means no.

I had a similar argument with a friend of mine in Croatia, he sought to correct me on the details of a remark I made concerning his country’s recent invasion of Austria. While he informed me that a deal had been in the works, that the plan was to give Austria a Q5 hospital (the usual price for a country to sell itself out) in exchange for letting Croatia run through to get to Western Europe, where the rest of EDEN is dogpiling on France, at the eleventh hour, the Austria government backed out of the deal. Croatia, just like the US two months before, said screw it, we’re invading anyway.

What part of No don’t the aggressor countries of the world understand?

Croatia was put in the same position the US was in December. Previous administrations had worked with the Japanese government to secure a deal to use the “doorway” to Asia, Kyushu, to set up their military camp on mainland Asia in the hope of liberating China and India from their various Phoenix masters. Plans were made, but at the last moment, Japan rejected the idea. The US decided to invade anyway, making Phoenix actually, momentarily, look like the good guy, upholding Japanese sovereignty, giving credence to their right to self-determination, and maintaining the simple truth that any country seeking to act on concepts like liberation and freedom needs to accept:

No means no.

The proUS and proCroatian sides told me up one way and down the other, these plans were good to go, all sides were in agreement, the concepts weren’t jammed down the other country’s throat, all the i’s were dotted and the t’s were crossed. They were revving up their war machines, they were frothing at the mouth, and just as they were about to launch once more into the breach, that most irritating of nuisances jumped into their faces:

No means no.

It doesn’t matter what the ultimate goal is, folks. No means no.

Americans were talking major trash about Japan, the Righteous Nation, and then-President Dokomo. Some were taunting them, some were making the argument that the invasion was for the “greater good”, some made the childish complaint that if Indonesia could use the “doorway”, why couldn’t they? The problem with any justification of the action is, no matter the argument, it requires you momentarily suspend your belief in such noble notions like democracy, self-determination, and sovereignty, and when you do that, you no longer stand for those noble notions; they become punchlines, bumper sticker slogans, excuses.

I don’t believe Croatia wants to steamroll through Austria in order to liberate anyone, they just want in on the action, hence the “greater good” argument isn’t applicable. The even more basic argument, however, does:

No means no.

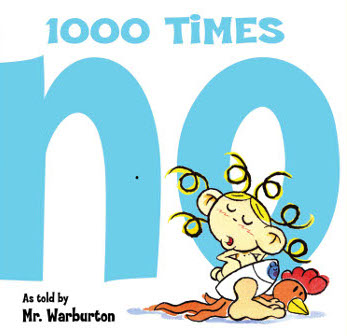

It’s a concept we’re taught when we’re toddlers, just learning to speak, just beginning to understand language. It’s one of the very first words we’re taught. No, Arjay, don’t stick that pencil in your mouth, you’ll choke. I said No, you can’t have five dollars to go to the arcade to play Donkey Kong all day. I told you, No, you can’t hang out with your friends until you finish your chores. As we get older, we start to realize that No isn’t just a word parents use to control their children, but an empowering word we use to set boundaries and ward people off. No, Arjay, my Dad will ground me if we hang out past my curfew. I don’t care, Arjay, if you paid for dinner, No means No, so accept this goodnight kiss, because that’s all you’re going to get.

I truly hope these eAmericans and eCroats, the ones who don’t understand the concept that No means No, don’t intend on dating my real-life daughters. With that attitude, they can expect me to be chasing them down the street with a baseball bat with nails sticking out of it if they don’t respect the No.

This is a game, and many people tell me to stop bringing in real-world concepts, mostly as a way for me to stop putting the spotlight on them when they do things even they believe to be wrong, but it’s just a game, so screw Arjay if he has a problem with it. Like any game, however, there has to be a level of a real-world concept called trust, or else social games just don’t work. An employee trusts his company has enough money to pay for him to work that day. Generals have to trust their soldiers will show up on time for a key battle. Governments trust their ministers will be their every day to perform their daily tasks to keep the country vital and safe. As such, your word becomes your bond, and that trust is built upon those bonds getting stronger. If you can’t respect the No, how strong can you possibly build your social network, if you can’t be trusted with something as simple as respecting the No?

And No, it’ doesn’t matter if plans were in the works for months in advance, if the other party wishes to back out, the plan is null and void, and if you blow the No off and decide to go through with the invasion anyway, you’re the bad guy in this, completely and unequivocally. You can point fingers all day long, you can blame the other party for reneging on the deal, but ultimately, they said No. If you go ahead and do whatever it is you were going to do anyway, that’s your business, just don’t complain about it, don’t try blaming the other guy, don’t cry when your neighbors suddenly stop trusting you, and don’t make excuses. You gave the middle finger to the No, you need to man up and accept the consequences for your actions.

I have yet to find the government ballsy enough to step up and say, yeah, they said No, but we did it anyway, deal with it. The Americans sought to justify ignoring the No with the “greater good” argument, hence, they made excuses. The Croats I’ve talked to are all pointing fingers at Austria, it’s their fault, how dare they act on their own self-interests, don’t they know a deal is a deal?

A deal is a deal when two parties not only agree to terms, but carry through. If one party backs out, the deal is off, and the other party accepts it as such. Countries like the US and Croatia can’t blame the other country for backing out, apparently on some level, the deal was not acceptable. The mature and professional thing to do is not to ignore the No and carry through anyway, making excuses and pointing fingers all the while, but rather, to go back to the drawing board, find out what went wrong, re-examine the plan, and make it better. Instead of crying and calling names, how about a little reflection, a little understanding, trying to figure out why the other party backed out, go back to the drawing board, find the problem, and correct it? What’s wrong with that as a way to deal with the No, instead of blowing it off, doing your thing anyway, and pissing everybody off, all the while you making yourself look like a thug who can’t be trusted and will say to hell with anyone who gets in our way?

I have a deal with my real-life boss, I work for him to the best of my abilities, and every two weeks he pays me. That’s the deal. If I back out of the deal and decide to work elsewhere, I doubt my boss is going to say, screw it, Arjay, a deal is a deal, and I’m going to pay you whether you show up or not. Conversely, if my boss blew all his money betting on the horses and can’t pay me, I’m not going to say, Boss, you’re backing out of your end of the deal, but a deal’s a deal, and I’m going to work for you, whether you like it or not.

As such, if Japan or Austria back out of their ends of the deal, the deal’s off. Period. The US and Croatia have no more deal to work with. Their invasions, no matter how they spin it, are unjustifiable.

That’s my answer to these sorts of situations. It’s a very simple premise, but apparently not one so easily grasped. Infants know what No means, why don’t the governments of the US and Croatia?

Comments

Meh lieks.

Why does your rant about Croatia and Austria have to be about the US? Go somewhere else with this crap. The US didn't attack Austria so publish your nonsense in a country that cares.

London says "no" too. ;P

good article. i dont care if our gov does stuff like this, but i too wish they would admit what they did instead of make excuses

"A deal is a deal when two parties not only agree to terms, but carry through. If one party backs out, the deal is off, and the other party accepts it as such."

Not true.

If the first party breaks a deal, and the second party suffers damage due to that, under certain conditions, the second party can claim damages. And that is exactly what we did. We claimed damages, because a plan was already set in motion, when eAustria decided to quite. You don't quit in the middle of something. This was not a "No means NO", but, "UH, I've changed my mind, screw you", kind of a situation, where we had to react in the way we did!

I am sorry you failed to understand that through our correspondence.

What part of yes doesn't the other side understand?

It seems to me that when two parties have positions they cannot reconcile like this, they have another level of politics to resolve their disagreement: war.

I remember Emerick winning that debate back in December, hands down.

Regardless, this is just... meh.

Must be something in the water. I'm not impressed with a lot of things people are doing today.

What part of "Burn London" don't you understand? 😉

I absolutely agree with you.

And I have to add- the one country that actually understood a "No" as an answer that was being said to them was Serbia some months ago when they wanted to pass through Bulgaria. They respected our wishes and left us in peace.

Also, respect for Phoenix for respecting Austria's decision not to take sides as much as we hated this.

Don't get me wrong, PEACE had its fair share of problems with understanding "No." It was no good and I never liked that.

no vote...

What I wonder is how there could have been any kind of deal that A- Nobody knew about B- was made what, 3 days into the presidential term? and C- As far as I know the deal became 'Do it or we attack' near the proposed war-time.

This isn't a deal, it's a threat. 🙂

Arjay, I wonder what Croatia will be saying once they are pushed back and somebody is taking over their country? I would like to find out, personally. I wonder if their famous "It's just a game" Slogan will stay. 🙂

"The problem with any justification of the action is, no matter the argument, it requires you momentarily suspend your belief in such noble notions like democracy, self-determination, and sovereignty, and when you do that, you no longer stand for those noble notions; they become punchlines, bumper sticker slogans, excuses."

While these aspirations are noble, as you say, there really is no basis for believing that these truly work to the extent you want. In RL and in the game, might makes right, whether that means military strength or money. Is it right? No. But it's prudent. And it works. And it keeps you alive.

Yeah right. Croatia said no to Hungary and they attacked us. Remember WW2

Why am I still subbed to this ridicules excuse for a troll?

No, means no and conversely yes means yes. Therefore both sides are in the wrong from the evidence presented in this article. No one has the moral high-ground in this argument. This article is written for no other reason than to be inflammatory.

I can't really unsubscribe again, but if I could I would.

I really hate the majority of your commenters. "might makes right" seriously? seriously?!? dude... your life must be completely meaningless... anyway nice article. I didn't finish it all because I've got to leave for class but I read most of it and I agreed with the point to begin with so no explanation necessary.

too long. unfortunately, I read it...

War is the continuation of diplomacy by other means.

Croatia made no promises of the nature of a NAP, and without them, Croatia is not a bad guy, just a guy with a place to be and someone trying to stand in his way.

What part of 'This is a friggin GAME based on conquest and war' do YOU not understand? Article is full of FAIL

cut the bullshit

if someone is standing in your way...and answering NO (as you suggest)to your efforts to make a peaceful deal...what can you do?

I doubt that any country said Yes...take our land...do whatever you want

so we should sit home, work and train, or write stupid articles like this one to make elife less boring.....and pray that one day some country will say: "take my territory (PLEASE)

you are trying to confuse people and make doubts even if there is no reason for any

this is strategic war game, and if you don't like me you should play farmville...i think you could fertilize your neighbors crops very well...and hope that one day they will say YES...take my farm

HAIL CROATIA

HAIL EDEN

*this is strategic war game and if you don't like IT (not me)

my bad 😉

and i forgot 2 things

i say NO to sub and NO to vote

and no means no so you are not going to get any

you know what arjay...you right...you right,Croatian ppl are like that and i admit it...i have to live it ,but i like my ppl how much they are bad or "stabbing me in the back" ...i still love them...cuz this is my home,

moja njiva,moga konja griva,moja krv ziva

...true to be told...90% of worlds population don't take NO as a answer...just like serbians...NO you can't win at Slavonia,oh what a heck lets try...what would you do when your neighbour said NO when you asked him to get out of your house,or don't interfier in you plans?...would you pull back?

oh yea...this is a good RL articl...but this my friend is a game : )...so don't mess up RL with a game...but a hell of a articl : )

Jel vi ne možete ama nijedan komentar da ostavite da ne pomenete Srbe?

stvarno ste opsednuti...

This is far too rambling, poorly written and generally stupid for me to want to read.

Wladimir, u mentioned Srbs as well 🙂🙂

to long, really, but it has a clear point.

I'm not going to join this debate, since is obvious who is right.

no means no, and rape is rape, even when a girl changes her mind in the last second.

what I don't understand is what's the big fuss about it. you're all acting surprised and hurt when somebody calls you by your true name.

Man up, accept the facts, and don't write those whining comments 'we didn't want to, they made us do it'. It's insulting everybody's intelligence. Next time call it an ultimatum, and you might get respect.

I have to disagree with the chorus of derogatory responses. The article makes a clear point, an it is not to judge the action, but the pretense of "noble" justification of the action.

Something I told eRomanians when they tried to play friends to eBulgaria after deleting us off the map. Ironically they used the same justification, it's a game, we had no choice you didn't agree so it's your fault. This mind you is the most RL life aspect of the whole isue in question, because it is the standard way of "morally justifying" actions which is used everyday.

So I agree with the author, nothing wrong with being the aggressor, just man up to it.

@Lord Marlok:

Dobar, dobar 😃

Lesson for eCroatia:

When we wanted to go through eBulgaria to reach our goal in november 2009. they didn't want to let us, so what we did?

They said NO, and we responde😛 NO it is.

Today eBulgaria is one of our most respected allie...

And eSerbia, although an "imperialistic" e-country, never commited agresion against other e-nation (eCroatia was attacked several times for mutual fun 😃).

I only read about half of it, but I think I pretty much got the point of the article.

Anyway, respect for other countries is based on strategy, not ethics. There's no reason a nation simply must respect other nation's sovereignty.

gruesome grammar.

Yes, this is just a strategic game. It is more interesting when there is some action. But if you look in the Croatian Congress you will see that they voted several times for an attack on Italy and the emperor apparently because Italy has several hundred more active players and gold then Austria. Smart are these eCroats!

Instead of having 2 hospitals.....

NO means NO hospitals at all.

Actually if we all respected NO from each other, there would be no wars at all in this game. Now, how long would there still be a game with no wars in it???

For president of Austria - we will still pass through, only you will not get anything from it. You should resign for being such a bad diplomat.

Nena😛

HAAHAHAH nice one.

The truth of the matter is.... u probably won't believe this... but last two presidents... believe it or not... accidentaly pressed the button 🙂. this was openly admitted by the last president 🙂