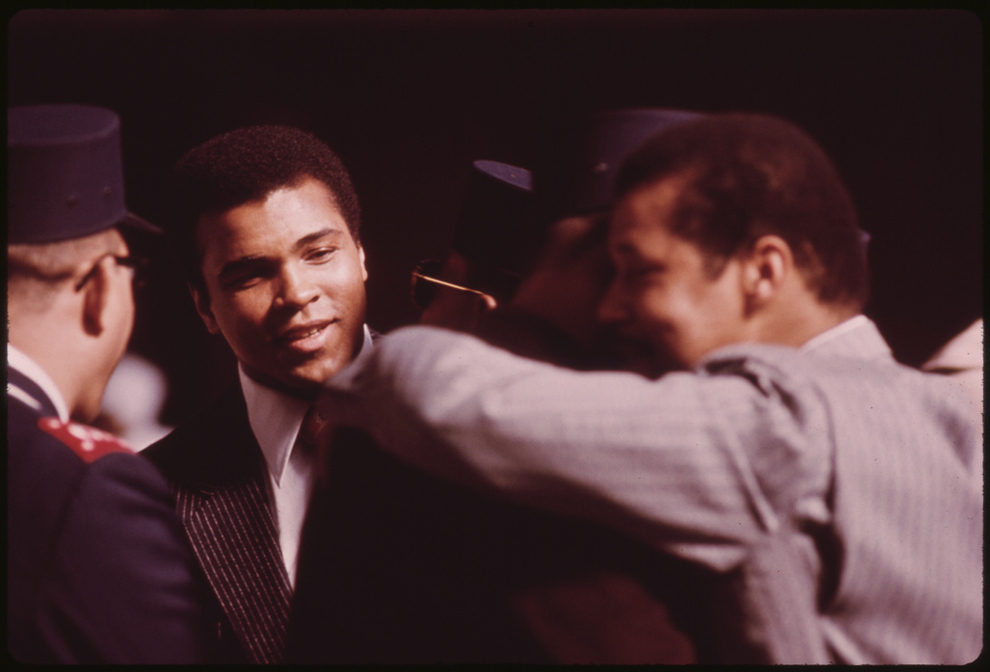

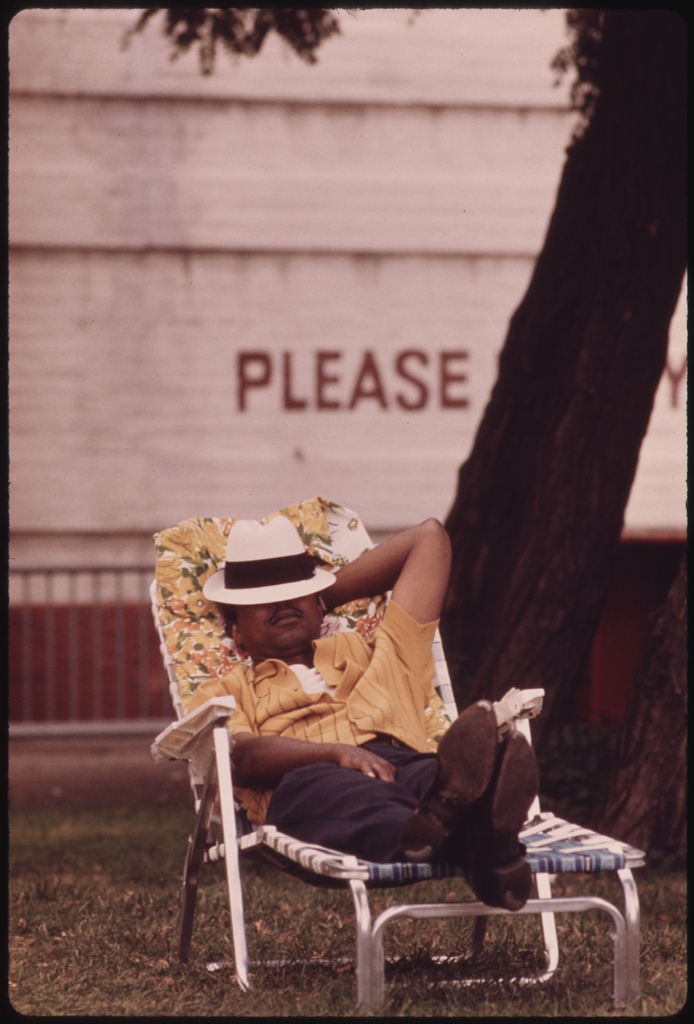

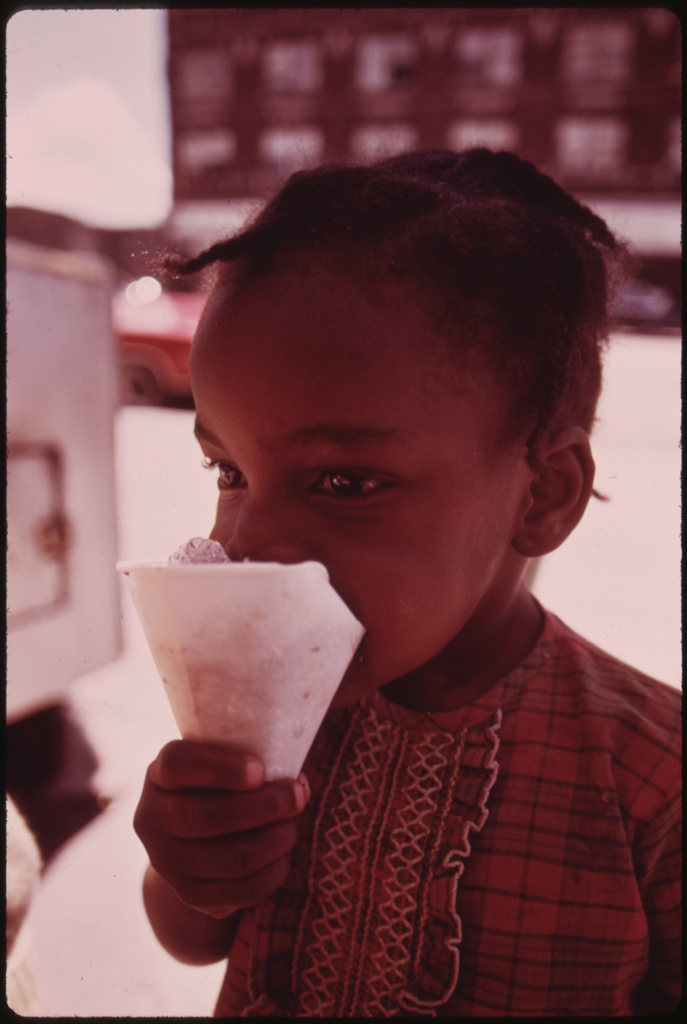

Everyday life of Chicago's African-American community in the 1970s

•

by

•

by Clark.Kent

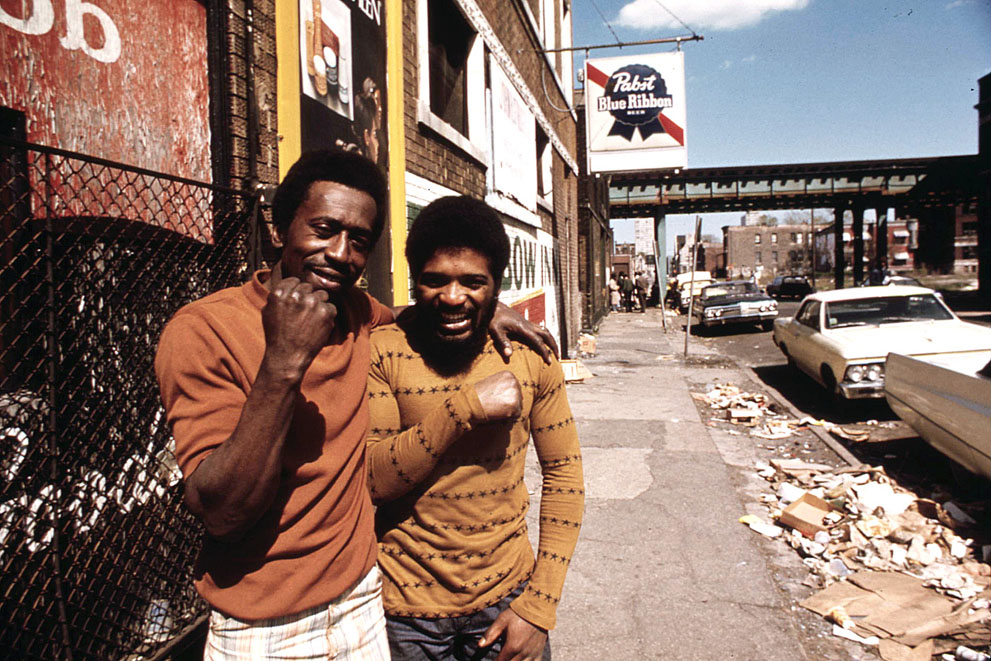

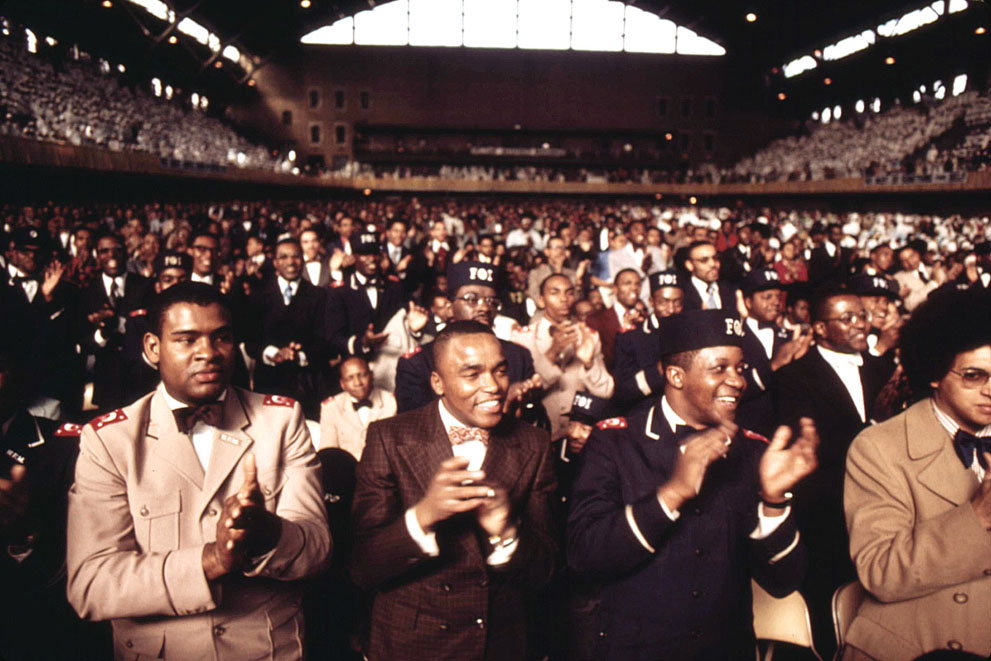

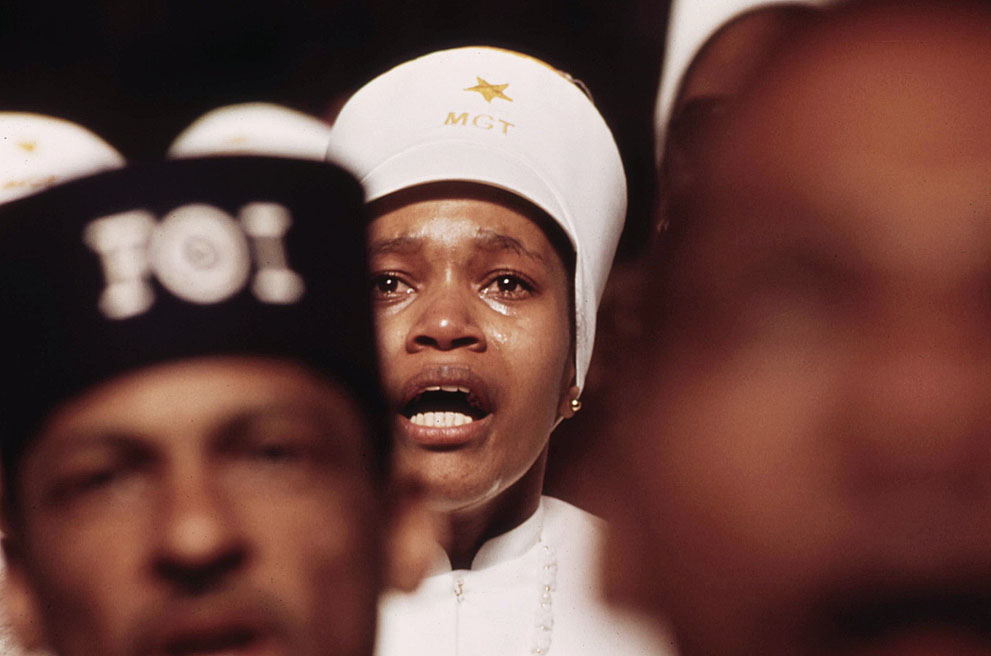

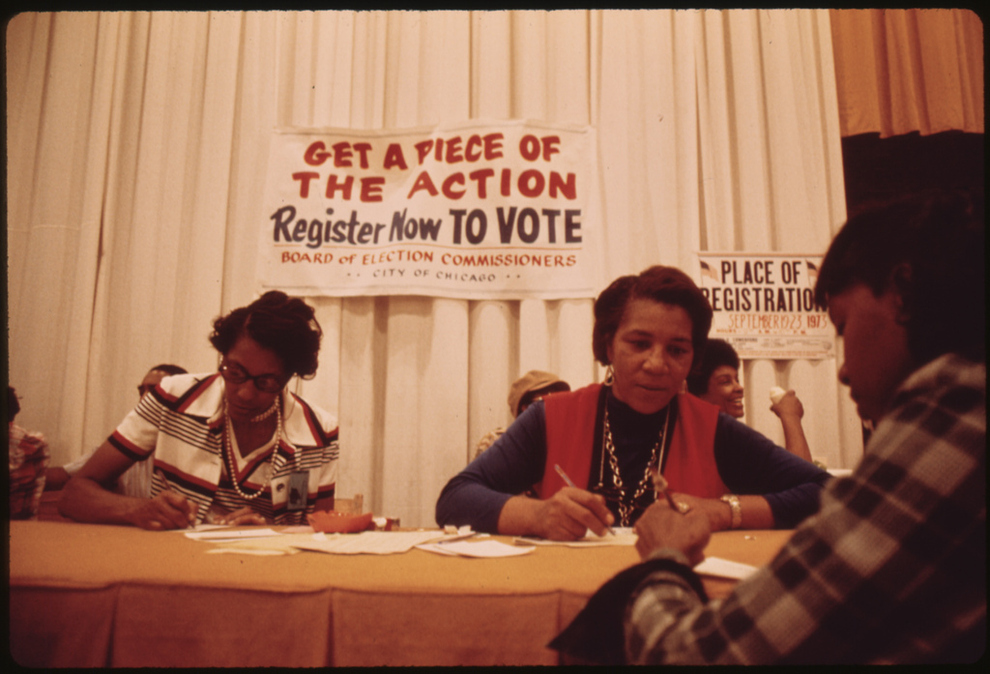

These photographs show Chicago’s African-American community, primarily the South Side, and are taken by photographer John H. White, who went on to win the Pulitzer Prize for Photojournalism in 1982.

His portraits of everyday life stand the test of time, inviting the viewer to travel back a few decades, and see just how we lived.

In the 1970s, White was hired by the Environmental Protection Agency to document the lives of the black residents of Chicago. For years, White explored the city, making intimate and powerful pictures of neighbors and strangers, capturing Chicagoans in states of joy, sorrow, reverence, and celebration.

As White reflected recently, he saw his assignment as “an opportunity to capture a slice of life, to capture history.”

His photographs portray the difficult circumstances faced by many of Chicago’s African American residents in the early 1970s, but they also catch the “spirit, love, zeal, pride, and hopes of the community.”

.jpg)

White was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Photojournalism in 1982 for his “consistently excellent work on a variety of subjects.” He was selected as a photographer for the 1990 project Songs of My People.

White has also won three National Headliner Awards, was the first photographer inducted into the Chicago Journalism Hall of Fame, was awarded the Chicago Press Photographer Association’s Photographer of the Year award five times, and, in 1999, received the Chicago Medal of Merit.

Hal Buell, the former head of the Associated Press Photography Service, noted that White is one of the best photographers at capturing the everyday vignette.

White has said that he lives by three words: faith, focus, flight. “I’m faithful to my purpose, my mission, my assignment, my work, my dreams. I stay focused on what I’m doing and what’s important. And I keep in flight—I spread my wings and do it.”

.jpg)

Chicago’s black population developed a class structure, composed of a large number of domestic workers and other manual laborers, along with a small, but growing, contingent of middle-and-upper-class business and professional elites.

In 1929, black Chicagoans gained access to city jobs and expanded their professional class. Fighting job discrimination was a constant battle for African Americans in Chicago, as foremen in various companies restricted the advancement of black workers, which often kept them from earning higher wages. In the mid-20th century, blacks began slowly moving up to better positions in the workforce.

.jpg)

The Black Belt of Chicago was an area that stretched 30 blocks along State Street on the South Side and was rarely more than seven blocks wide.

With such a large population within this confined area, overcrowding often led to numerous families living in old and dilapidated buildings.

The South Side’s “black belt” also contained zones related to economic status. The poorest residents lived in the northernmost, oldest section of the black belt, while the elite resided in the southernmost section.

In the mid-20th century, as African Americans across the United States struggled against the economic confines created by segregation, black residents within the Black Belt sought to create more economic opportunity in their community through the encouragement of local black businesses and entrepreneurs.

During this time, Chicago was the capital of Black America. Many African Americans who moved to the Black Belt area of Chicago were from the Southeastern region of the United States.

.jpg)

The migration expanded the market for African-American businesses. “The most notable breakthrough in black business came in the insurance field.”

There were four major insurance companies founded in Chicago. Then, in the early 20th century, service establishments took over.

The African-American market on State Street during this time consisted of barbershops, restaurants, pool rooms, saloons, and beauty salons.

African Americans used these trades to build their own communities. These shops gave the blacks a chance to establish their families, earn money, and become an active part of the community.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Comments

ο7

first

Successfully transferred 600 item(s) to Lady Moon4.

Exellent article, dear friend.

You're an intelligent person

V + E. o7

Successfully transferred 300 item(s) to Gustibus.

V4

Sub 1109

o7

Successfully transferred 300 item(s) to eShone085.

beautifull people 🙂

Successfully transferred 300 item(s) to KOLAK79.

I love these photographs. Another amazing article from you. 🙂

No need to send anything.

tx for the support

o7

Successfully transferred 300 item(s) to Marko Livaja.

Great Muhammad Ali

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to Obi Wan Simio.

V12 Sub1110

Good photos

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to Dr.Makina.

v13

Good newspaper

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to M.H.P.C.

V 14 s old

Successfully transferred 300 item(s) to windows2012server.

hue /o

Successfully transferred 300 item(s) to FragUK.

o7

Successfully transferred 300 item(s) to Dvetebiri.

o7

Successfully transferred 300 item(s) to Jack Morgan Jr..

Great pictures. Sweet Home Chicago. Love the Blues.

Successfully transferred 300 item(s) to LanyIsLost.

Interesting article and photos! 🙂

(No need to send anything!)

tx for ur support

o7

Successfully transferred 300 item(s) to The Real Elefantescu.

Looks happy;

Successfully transferred 300 item(s) to lesnydziadek.