On the question of the e-proletariat

•

by

•

by Pfenix Quinn

Song: Man in Black

These notes are in response to a question posed by comrade-brother-scientist Max Planck in Part 2 of his series on the SFP Constitution. They are exploratory notes and don't pretend to answer any questions precisely. ENJOY!

First, let's underline the distinction PQ made in "Analysis of Classes in eRepublik" between the game context and real life. This has two important dimensions: difference and interpenetration.

I'd also like to note right up-front that PQ's "Analysis" was itself a pastiche on Mao Zedong's "Analysis of the Classes in Chinese Society", and thus it can be read both as a joke and as a "serious" examination of the structural imbalances within eRepublikan "society".

First dimension of the distinction: Difference

Pablo Iglesias Turrión is the Secretary-General of Podemos, a leftist-progressive political party that grew out of the Spanish Indignado movement -- what in the US we called the "Occupy" movement. He is currently the Second Deputy Prime Minister of Spain, part of the recently-formed left-socialist coalition government in Madrid. In a Jacobin article late last year, he wrote: “Trying to transform society by mimicking history, mimicking symbols, is ridiculous. There is no repeating other countries’ experiences, past historical events. The key is to analyze processes, history’s lessons. And to understand that at each point in time.”

I'd offer that Pablo's advice is likely useful for other real life leftists and progressives. And it applies for e-life too, but with the codicil that in the New World, being ridiculous is part of the fun!

In other words, while it's sensible to clarify that the e-proletariat in eRepublikan history is not precisely the same thing as the proletariat in modern real world history, just noting that there is, obviously, a distinction does not paint the whole picture either. But I'd certainly agree that there is a difference. And that if one wants to be "serious" about e-class analysis -- keeping in mind, imho, that this is a somewhat dubious undertaking -- then, per the advice of Sec-Gen'l Iglesias, just mimicking a few Marxist nostrums is unlikely to be fruitful in any pragmatic sense. Though it might well be ridiculous, which, again, is not necessarily a bad thing.

Kind of along those lines of ridiculousness, we have seen a few quite hilarious "Comrade Stalin" avatars bouncing around in eRepublik, for example. There is language in the SFP Constitution that plays around in this mimicky way too, all in good fun.

So there's that. Summarizing this dimension of the rl/eR distinction on this question: the internally-consistent social and economic context of the game world is indeed quite distinct from that of real life; confusing them can be funny, but probably not terribly meaningful or successful in a political sense, which for us means in a social-revolutionary sense.

Second dimension of the distinction: Interpenetration; or, There's a Crack in Everything, That's How the Light Gets In

While RL and eR are -- and should be understood to be -- distinct, the other important dimension of that distinction is that they also interpenetrate with respect to economic status/capability/choice and regarding ideology/intention/class consciousness.

Along with yet another caution to not confuse things too much between a game context and real life, this dimension was also explicitly called out in PQ's "Analysis".

Later on in the "Analysis", PQ dug into the intersection between real life and the game world in more detail, describing the nature of the software itself, the fact that it is not free and open source, and looking at the intentions of the (for-profit) company that produces it. An argument is put forward for understanding becoming or being "haute bourgeois" (what nowadays we might call the "one percent") within the New World e-context to mean aligning one's approach to game play with the capitalist goals and (from a libertarian-software-developer perspective, the somewhat authoritarian) proprietary technical methods of the game's designers and owners.

Then it went on to represent, in a fairly vague way, a kind of class identity, or at least, let's say a class reflection, between players who either choose not to, or cannot for RL economic reasons, spend cash on the game with something like a conscious revolutionary class within the game world. And finally it called on "revolutionaries" to "wake up" within the game context and to pursue tactics and strategies employing, essentially, détournement and alternative approaches to game play as a means for expressing e-class-conscious e-proletarian ethics.

I'd add that by observing that over the e-years, in a wide variety of ways, fidelity to the idea that popular culture can and should be a site for ideological struggle has been expressed by folks like Osmany Ramon, Leon Gutierrez and many others in the SFP, as well as by individuals and groups in the eWorld -- the French "parti koinmuniste" being one of my personal favorites -- following a similar ludic approach, either explicitly in exegeses like this one, or through their creative play.

In the real world, thinking the interplay between economic base and social/cultural superstructure, as some sociological formalists like to put it, has been explored by radical thinkers through explicit analytical works like Antonio Gramsci's analysis of cultural hegemony, and in works like Guy Debord's Society of the Spectacle and its predecessors like Henri LeFebvre's Critique of Everyday Life.

A literary engagement in class struggle -- and by that I mean bringing the struggle of the proles into the realm of the arts, and not simply creating propaganda -- was also the hallmark of the famous modern Chinese writer, Lu Xun, whose students formed the delightfully-named "Yet to Be Named Society" in Beijing in the 1920's. Even prior to that, in modern English, French and Russian literature, in the naturalist works of folks like Victor Hugo, Émile Zola, Maxim Gorky, Charles Dickens, Fyodor Dostoevsky and Louisa May Alcott, we see even earlier attempts to bring radical thinking about the "real" into the realm of fiction, which was the masively multi-player social playground of their day.

Bonus Song Track!: Worker's Song

Second, let's consider what we mean by the term proletariat.

There is so much bullshit, so much reification, so much spectacularization, so many opportunities for ridiculous mimickry, that I am nervous about even approaching this topic. But never let it be said that RF Williams refused to engage, in depth, on a hopeless quest for ontological clarification...

Maybe the Dropkick Murphys said it best in the Worker's Song: "We're the first ones to starve. We're the first ones to die. The first ones in line for that pie in the sky. And we're always the last when the cream is shared out."

That captures it better, I think, from an overall strategic perspective, than any number of reductionist-Marxian arguments on why industrial factory workers are "naturally" the foundation for creating a new society.

Collective Power

But.

Don't get me wrong. The historical movement of people leaving the land to work for wages in the cities was a sea change in human history. It ushered in a new kind of slavery and, in response to that, a new kind of collective politics, new economic possibilities, and new ways of both thinking about and handling the distribution of a nation's wealth.

It might be interesting to see if there weren't some possibilities for labor unionization within the game context. I doubt it, but maybe. We have certainly seen a "natural" movement towards voluntarily collectivizing of e-labor in the form of various "commune" schemes over the years. Although it's a natural extension of game mechanics, it is also interesting to note that this kind of thing had to be consciously brought into the game by groups like the SFP (and others), not by Admin, introducing forms of collective play that were not part of the originally-designed game model.

So there is that aspect of in-game "industrial working class" and its class-character, if you like, which does get expressed in eRepublik: the workers are more powerful when they pull together.

Leaving the e-analysis at this level, however -- as Osmany Ramon pointed out long ago -- tends to miss understanding that there are aspects of exploitation and alienation within the political economy of eRepublik.

Exploitation

Since all eRep play is voluntary, an argument for exploitation of one's e-labor is necessarily a fairly abstract one. To the extent one does the "self-employed" approach to work, then at best the exploitation involved would have to be considered maybe something more like a kind of over-indulgent selfishness, perhaps like a worker from poor family who contributes nothing to the family's well-being and only lines his or her own pocket. Still, that's quite a stretch in eRepublik.

Looking at structurally, within the game context, there is a wage system, which in turn is based on the somewhat wonky market economics of the default ludic framework. "Employers" can offer higher wages in order to attract more "workers". It is possible to work "overtime" via various in-game mechanisms. In such arrangements, the profits from selling goods manufactured may or may not exceed the cost of paying workers. If so, then this can be understood, formally, as exploitation in the sense that the workers are not receiving the full benefit of the wealth they produced, especially once the "owner" has re-couped their initial capital investment.

Some of the more convoluted commune schemes have addressed this by collectivizing the capital investment in an open and transparent way. Basically, a co-op. A group buys the needed factories and resources and so forth, and members are paid back according to their investment. Then wages are paid out "in full", reflecting market conditions, but without a single individual reaping the profit. This kind of approach is also referred to sometimes as a "high wage commune".

Somewhat ironically -- if one has no appreciation for dialectical humors -- "low-wage communes" are the most exploitative type of e-labor arrangement. Workers are paid well below market norms, and well below the value of what they produce.

The buy-in, or pay-off, depending on your favorite ontological explanation for such motivations, is typically something like "for the good of the militia (or nation, or cult)". In other words, we volunteer to work cheap in order to maximize our group's ability to arm itself. Since it is entirely voluntary this type of thing is not particularly alienating -- perhaps even the opposite -- but it clearly is exploitative in a formal sense.

Alienation

Regarding alienation from the fruits of one's labor, eRep's default political economy works almost exactly like in real life. One produces "goods" for a market, not for one's personal consumption, through the medium of currency exchange, which is itself a highly abstract market entirely divorced from the actual day-to-day human-player needs of e-workers and their affinity groups.

Again, various mutual-aid programs, like the SFP's free tanks and housing-reimbursement programs (and many other groups have similar ones), and some of the commune schemes work to counter such alienation.

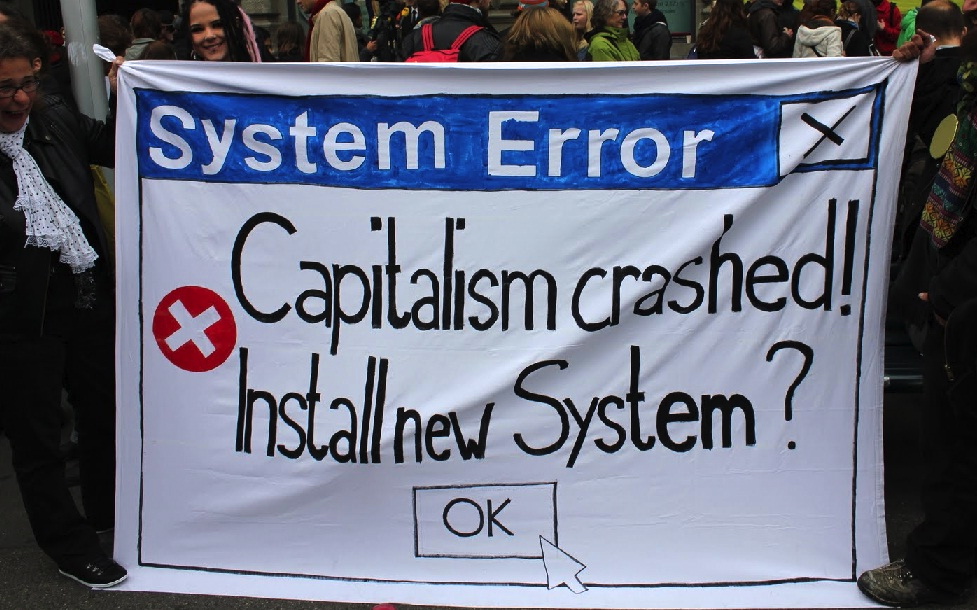

It is interesting to note that Admin eventually developed the "gift" object, which was evidently designed to encourage this type of "gifting" or "potlach" economy but has quickly been reified into another commodity -- an outcome that should be entirely expected as long as the game's foundational economic system is based on market exchange. Similarly, "surprise" at communes becoming exploitative and alienating simply reflects the ease with which the capitalist system can gobble up and seek to monetize virtually anything, as well as the rapidity with which "socialist" mimickry can lead one down a capitalist road. (See the ad for "Proletariat" beer.)

This economic sense of "alienation", as opposed to the psychological or family-dynamics senses in which the term is often used, is what Marx called "the fundamental evil of capitalist society". This line of critique is increasingly heard these days, in real life, from advocates of social ecology and from those concerned with environmental degradation and species extinction. Which is to say: if the only value of what we do is how it is monetized, then we are losing touch with our humanity (and with our Mother the planet, and literally with our mothers, in the sense of losing the sense to care well for our families, our neighbors, and our homes).

The often-heard comment about "community" being the best part of the game is an in-game reflection of the proletarian desire for a world where life is more important than money. Though I find it difficult to even understand the mechanic, much less have an opinion on how it might be usefully détourned, the introduction of "pollution" by Admin is also interesting in this context and might (or might not) be a fun story-line for e-proletarian activists to take on.

The Rabble

Along with doing little or nothing to alleviate the suffering of the poor, uncontrolled market-based economic systems, which can be innovative and energetic, also tend towards periodic monetary crises due to treating "growth" as their prime directive. In biology, this type of thing is called "cancer". Likewise, in the study of animal evolution, there is a clear trend towards relatively rapid extinction for the large-sized species, where as the tiny ones seem to endure. As J.B.S. Haldane (often misattributed to Charles Darwin) said : "God is incredibly fond of beetles."

Hegel believed that social crises would eventually work themselves out under the benevolent utopian gaze of a enlightened monarch. He alludes to an excess of divinity, if you like -- the king, the leader -- at the top of the social edifice, that he believed was the necessary engine for working out and resolving social antagonisms. Marxists agreed with much of his analysis, but not his conclusion, and saw the newly-developing industrial working class instead as that engine.

I'd note that Hegel also pointed out in Philosophy of Right that such an elite is supplemented by an excess at the bottom of Pöbel, which we can translate as "the rabble" or "the mob". It is worth briefly quoting his characterization of it:

"When the standard of living of a large mass of people falls below a certain subsistence level ... and when there is a consequent loss of the sense of right and wrong, of honesty and self-respect... the result is the creation of a rabble of paupers ...[and]... the concentration of disproportionate wealth in a few hands."

Adam Smith had some interesting things to say about impoverishment too, in his Theory of Moral Sentiments, where he encouraged his readers to grasp the importance of human solidarity:

"What improves the circumstances of the greater part can never be regarded as an inconveniency to the whole. No society can surely be flourishing and happy, of which the far greater part of the members are poor and miserable."

If we want to go back a bit further into our sources of anarcho-communist thinking on this, we can see that the Gospel according to James, chapter 2, verses 14-18, gave an interesting point of view on praxis vs. blabbing or just "thinking good thoughts". The gospel-writer wrote:

"What good is it, my brothers, if someone says he has faith but does not have works? Can that faith save him? If a brother or sister is poorly clothed and lacking in daily food, and one of you says to them, 'Go in peace, be warmed and filled,' without giving them the things needed for the body, what good is that? So also faith by itself, if it does not have works, is dead. But someone will say, 'You have faith and I have works.' Show me your faith apart from your works, and I will show you my faith by my works."

Further on back into the mists of time, we read in Proverbs, chapter 31, verse 20, about the spirit of the Lord that...

"She opens her hand to the poor and reaches out her hands to the needy."

In both of these Biblical injunctions, we can infer that, for many centuries now, radical thought leaders have understood that "good intentions" are not enough when faced with the realities of poverty and injustice.

Coming back to our more modern saints, both Hegel and Smith described poverty as not only as a material condition, but also as a subjective position of being deprived of social recognition, of being deprived of autonomy, or as we might say today, of agency, to take care of one's own life. They saw that subjective freedom can actualize itself only in the rationality of a universal ethical order and that those whose dignity as persons is deprived, eo ipso, have every right to rebel.

In other words, charity is not enough either.

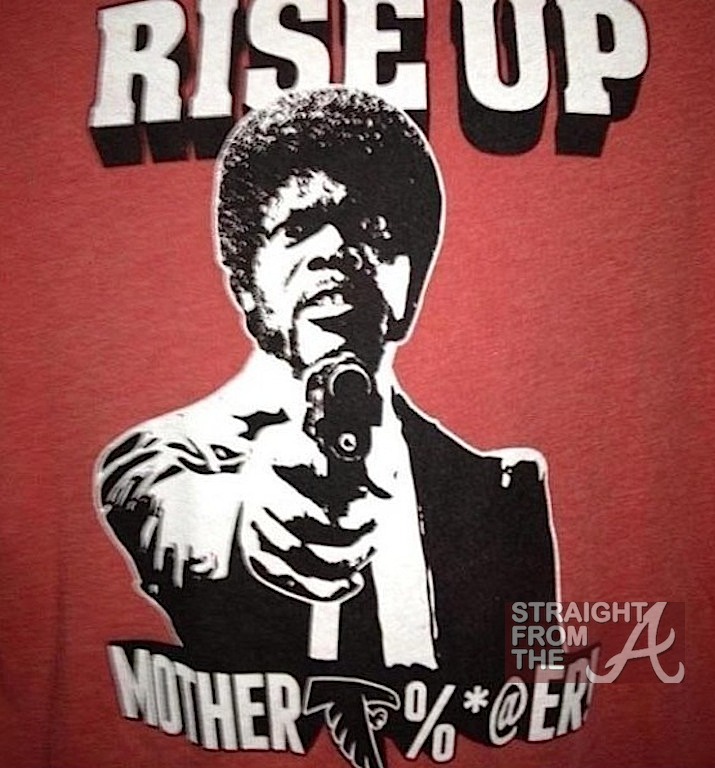

Rise Up

I dwell on all this in order to try to work out a distinction between my understanding (abstractly, so that I might be able to try to envision of a "literary" e-version of it on behalf of our very own "Yet to be Named Society") of...

"the proletariat" as (stereotypically, mimickly) the "woke" unionized industrial workers who are ready to seize and collectivize the means of production with the leadership of a communist vanguard and thus usher in a brave new market-less world freed from the monetization of everyday life (which is the fetishism of commodities)

vs.

"the proletariat" as (in all places, in all times, in all contexts) those who are without, those who are "other", those who have been shut own, put down, and ignored, those who have "failed" to monetize their lives sufficiently to "win" the unwinnable "market game", those who are hungry, who are weaponless, who are shirtless, those who are poor in things and poor in spirit.

I don't know if this (non-stereotypical) "proletariat" is the "engine of the revolution". But it seems to me that the revolution isn't worth much if it doesn't energize this proletariat towards liberation.

Thanks for checking out this edition of "Radio Free Dixie"! Please provide feedback and suggestions. If you'd like to have Lunch With Bob, drop me a line and I'll send you an interview form.

In-game: Use the handy comment section below, or send a message RF Williams, or go hang out with the libertarian-socialists for a while and chat me up on the Socialist Freedom Party feed.

Comments

I wear the black for the poor and the beaten down,

Livin' in the hopeless, hungry side of town

A very comprehensive and nuanced take on an interesting subject, I definitely see the utility to not reducing the eProletariat to any one economic factor in this game as it doesn't include the players who don't fall within that definition who also work to advance the movement. Your definition and analysis blows mine out of the water on this issue and i'll have to concede to your points 🙂

Thanks for responding to my question, was a great read!

o7

Occupy eRep!

So much of reaal life politics reflects in eRep. good to give so many ideas a place. o7

About the beetle: It eats so many other living creatures each day, it is far worse than a capitalist. On the other hand it saves crops for others. 😉

[removed]

There are two classes on erep: those who are above the rules, can breach any one of them without consequences, for example changing, trading characters, operating multies, and admins not only don't punish them but the game policy is exclusively to serve the sick game experience for which these players are willing to pay.

And there are us the proletariat, who would be banned if we did the same things, are whose game experience has been completely ignored and reduced to nothing. Some big players are now demonstrating against admins because "the game is not fair". They are the same beneficiaries of the system of the institutionalized cheatings. The real lower class is silent, unconscious and seemingly nonexisting.

There was only one class-type war in the game and that was the Hungarian coup attempt in June, in which a community of simple players defeated some arrogant costumers of this corrupt game. Hungary is the only country where the government has to comply with community requirements because this was enforced in war.

At the same time I have never seen the expressedly socialist, class-based ideas to touch real problems, they only remained abstract theories with no real connection to the game. While there are blatant conflicts of interests, obvious corruption on the part of the administration, despicable things from governments (for example yours), most of the players just accept it as normal and don't think they could or should do anything, even to talk about the problems openly.

It's too late but we should had said, if a multi is fighting on our side we are not stronger but weaker and the person who operates it is not ally but enemy because he is killing everyone's game. We should had said if some egoistical persons want to grow superpower the community is not stronger but weaker because they will finally kill the game of the communities.