The Chinese Language

•

by

•

by Yaakmo

Per Weihaiwei's request, today we'll be observing the Chinese language. Before going off on this long rant, it's important to understand just how old and lush the Chinese language is. Linguists currently speculate that a form of Chinese has been around since roughly 6600BCE (over 8000 years ago). This is considered one of the first records of a written language. Typically, linguists have trouble documenting the history of languages due to written languages being quite new in human history. But, this allows us to have a good understanding of what they would've been like. This 8000-year-old writing style was similar to Egyptian Hieroglyphs. It's speculated that writing had a pretty linear development: starting as drawings in a cave to replicate a story or event, going further into symbology, then into hieroglyphs or cuneiform, then finally into either ideographs or scripts. This particular style, found in Hefei, is a development going from cave drawings into a transportable writing surface: a turtle shell. Found on this shell were a few symbols, but one of the more important ones has to be the eye:

But this only shows the ancient aspect of this land of writing. When looking at modern mandarin (to be specific), it looks nothing like this turtle shell. For this article, I'll be using a similar layout as the English article, especially since I'm not knowledgable in the functionality of Chinese, but I know about the history of Chinese.

To begin, the family that Chinese resides in is called the Proto-Sino-Tibetan family. Like that of Proto-Indo-European, the root language is no longer known, nor have we ever truly seen what it looks/sounds like. Linguists have attempted to reconstruct Proto-Sino-Tibetan, but the other languages in the family make this a bit difficult. Chinese is very unique, but linguists have trouble finding well-documented languages within the same family (possibly due to Chinese campaigns and the dominance of the language itself). Not to mention, some languages around the Tibetan area are actually of Indo-European roots-- Hindu being the main one. Due to this, sadly, we may never know what Proto-Sino-Tibetan will look like unless documented languages appear.

Going past this unclear root, we have the original Chinese: Archaic Chinese. Becoming the common tongue of the land during the middle Zhou Dynasty (c.7th century BCE), several texts were made: inscriptions on bronze, the poetry of the "Shijing", the history of the "Shujing" and some portions of the "Yijing". Knowing of these artifacts (although a bit worn due to age), we have been able to begin the reconstruction of Archaic Chinese. This is also being aided by using the phonemes in modern Chinese. One of the main difficulties regarding tracing the history of Chinese has been the fact there are dozens of dialects within the language itself. Comparing Shanghainese vs Mandarin vs Fuzhounese vs etc. causes intense contradictions in the studies.

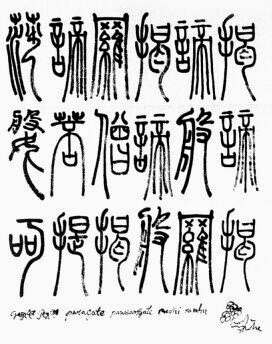

Going earlier in history begets Middle Chinese. Popularized c.600 CE, this language was very prominent in the Sui, Tang and Song Dynasties. In reality, this language had no real prominent changes compared to modern Chinese. There were a few phoneme changes causing a growth towards open vowels and inflections. One thing we can easily see is the change of the characters from Middle Chinese to Modern Chinese:

But, to be frank, that's about as vast my knowledge about Middle Chinese reaches.

Finally, we touch on Modern Chinese (Mandarin). Mandarin became a prominent language during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912 CE). But, there is evidence that Mandarin began during the end of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). After the Qing Dynasty fell, Mandarin was still instated as the country language and hasn't changed to this day (save for some slang, but that's every language). For the fun of it, let's touch on some of the sounds in Chinese since they're truly unique in several ways.

Chinese is under the classification of being a Tonal Language. This means changing the stress or the inflection on a phoneme alters the meaning of the word. This is typically why Chinese is very difficult for non-tonal language speakers, remembering which tone to use for which word causes issues, especially when you want to call the horse fat and not the person's mother (the word for horse and mother are just a tone apart). Alongside this difficulty of tone-usage, the writing system of Chinese is known for both its elegance and complicated nature. Chinese initially used pictographs (as seen by the eye above), which are just graphic representations of real objects to convey a sentence (I see you would probably be a person, eye, and another person). But over time, especially for the art usage of the language, characters began to become more stylized, representing both an idea and an object. Each character represents a syllable. They can represent words, but not every character can be used independently. Chinese is also known for its expansive character list. Note: Chinese does not have an alphabet like Indo-European languages, they don't even use a dictionary, they use something called a lexicon. Lexicons are vaguely the same as a dictionary, but lexicons are typically more expansive having every single word every used or identified from a language; dictionaries typically include only common words with some other uncommon words.

Without going off on a longer rant, I should end the post here. Like always, I'm not here to give you the entire history, but rather a "simplified" form of history, a glimpse not the full picture. I highly suggest you further study this language, especially since I can't rightfully do it justice. And, like always, please feel free to leave feedback, suggestions, or any questions you may have!

Thank you Weihaiwei for your suggestion!

Comments

You're welcome. I think some say the Qin Dynasty had heavy Indo-European tones but I could be wrong. Thanks again for writing.

All languages come from some root, we don't know what this root is, but this is why some languages have similarities even though they're from different families. I haven't heard of the Qin Dynasty being mentioned in regards to Indo European, but I have heard a claim about the Han Dynasty, which isn't historically held up right now. I believe they found oracle bones and someone made a claim that they're written with an Indo-European language, but it hasn't been backed up nor has it gained much weight within linguistics.

Gotcha. I think the person I was talking to was biased.