September 10, 1872

•

by

•

by Hunkakaricum

Lawyer and military hero of the Romanians of Transylvania in 1848-1849. Born into a peasant family of modest means in the Apuseni Mountains of western Transylvania, he received an education rare for a Romanian of this time, attending the Piarist lyceum in Cluj. He studied the humanities and then, between 1844 and 1847, law. After graduation he took a post as cancelist (law clerk) at the High Court of Transylvania in Tirgu-Mures, a mainly Hungarian city. It was here among some thirty fellow Romanian lawyers (and their 170 Hungarian colleagues) that the first news of the events of March 1848 in Vienna and Pest reached him.

In the revolutionary year that followed, Iancu's activities embodied the liberal and national aspirations characteristic of his generation. Like liberals elsewhere in Europe, he stood for individual freedoms, but the long struggle to protect the Romanian nation from subjugation by others had led him to put the interests of the entire ethnic community ahead of individual rights. Such a commitment explains the apparent paradox of his ultimate rejection of Hungarian liberalism in 1848. Yet, his brand of nationalism was by no means anti-liberal, and he displayed exemplary toleration toward the other peoples of Transylvania.

He thus belonged to the European generation of 1848, to that group of younger intellectuals who strove to change the old order of society and politics and who formulated the ideals upon which a new Europe could be built. He shared the aspirations of Young Europe, which manifested these ideals in almost every country before the outbreak of the revolution. Like his contemporaries in Italy or Germany, he believed in the compelling force of ideas, especially those of liberty, equality, and fraternity, and he had no doubt that he and his generation could reshape the Habsburg Monarchy to fit their image of the ideal state and could indeed transform all Europe. The enthusiasm he displayed in the spring of 1848 reflects the depth of his commitment. If his sense of universal brotherhood blurred his vision of underlying dissension among the peoples of the Monarchy themselves, and if his certainty of the ultimate triumph of justice obscured the resiliency of the old order, it was because he sought harmony and peace, not rivalry and conflict.

Iancu shared the romantic spirit of the age. Without it, his actions and the idea of nationality itself would be incomprehensible. His almost Biblical faith in the good sense and reasonableness of the common people and the inspiration he drew from the past, specifically, the Roman heritage of the Romanians, were manifestations of it. But he was also painfully aware of the ills of society, which he had first experienced as a child in his village. His later training in the law, when he read the enormous collection of legal acts illuminating the economic struggle of the peasants of the Western Mountains against rapacious landlords and state bureaucrats, sharpened his perception of social injustice. Like intellectuals elsewhere in Europe who had no vested interest in prevailing social and economic structures, he did not hesitate to urge radical solutions. But his proposals were never foolhardy or utopian, and he shunned the long and often abstract constitutional debates in which intellectuals often indulged. His identification with the aspirations of the common people served to anchor him in reality and thus enabled him to apply his reverence for the past and his robust idealism to the solution of fundamental social problems.

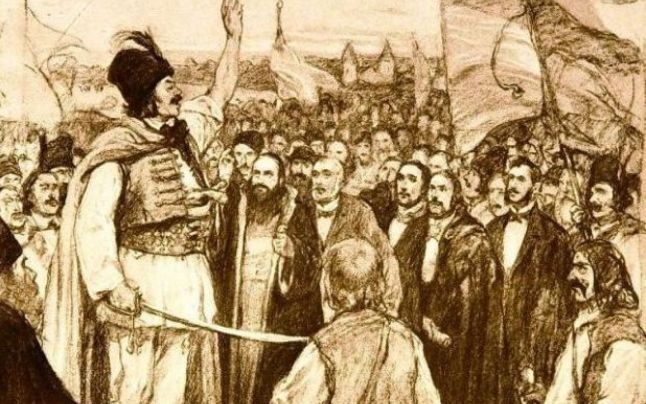

When Iancu learned of the flight of Metternich from Vienna and the declaration of civil and political freedoms by Hungarian liberals in Pest in March 1848 he enthusiastically joined his Hungarian colleagues in Tirgu-Mures in celebrating these events as the beginning of a new era of fraternity and equality. But he was also intent upon gaining recognition of the Romanians as a nation equal to the Hungarians and the other nations in Transylvania and assuring their development as a distinct nationality. He took part in the feverish preparations by Romanian intellectuals for the national congress on the "Field of Liberty" at Blaj on May 15-17, where he headed a numerous delegation from the Apuseni Mountains. He had only a modest role in drafting the national program and in choosing the means to achieve the goals it set forth, since he was younger than most of his colleagues, but he was soon to earn his place among the heroes of the Romanian revolution.

Iancu returned to the Apuseni in mid-June. Convinced that the Romanians must be prepared to defend their rights by arms, if necessary, he organized the peasants into what became the most effective Romanian fighting force during the revolution. In the fall of 1848, his army cooperated with Austrian forces in wresting control of western Transylvania from the Hungarian administration. But Hungarian revolutionary armies regrouped and between November and the following March under the command of the Polish general Joseph Bem they regained almost all of Transylvania, except the fortresses of Alba Iulia and Deva, held by the Austrians, and the Apuseni region, which were defended by Iancu's forces. Iancu eventually had some 20,000 to 25,000 men under his command, but the majority were peasants who had had no formal military training, lacked modern weapons, and whose officers were non-professionals, mostly lawyers like Iancu himself, or priests. Cut off almost completely from the outside, they endured severe hardships and, worse, a growing sense of disillusionment that their sacrifices had been to no avail in bringing to fruition the goals proclaimed on the Field of Liberty.

Despite the deterioration of relations between Romanians and Hungarians, Iancu still hoped to settle their differences by peaceful means and was thus receptive to attempts at mediation. In late April and May 1849 Ioan Dragos, a Romanian deputy in the Hungarian parliament, tried to negotiate a settlement between Iancu and Lajos Kossuth, the leader of the Hungarian independence movement. Both sides offered concessions, but the negotiations foundered on the fundamental question of national self-determination. Kossuth promised Romanians the same rights of citizenship as other nationalities and freedom of religion and extensive language rights in the new Hungary, but he insisted upon preserving Hungary's political unity. For his part, Iancu welcomed the liberal program of the Hungarians, but demanded autonomy for the Romanians as their only effective defense against as similation by the Hungarians.

In early June the Hungarians facing Iancu's army proposed that the two sides join forces to fight their "common enemy" the Habsburg army and bureaucracy as the only way of ensuring the liberties of their two peoples. Iancu responded that he, too, was eager to secure the blessings of liberty for his people, but the events of the past year had so shaken his faith in the Hungarians' promises that he would have to wait and see if they would transform words into deeds. In any case, the exchange was in vain, for Kossuth refused to modify his stand on Romanian autonomy.

The defeat of Hungarian forces by superior Austrian and Russian armies in August put an end to the revolution in Hungary and Transylvania and inaugurated a decade of direct rule from Vienna. Iancu was among the many Romanian leaders who journeyed to Vienna in 1850 and 1851 to urge the emperor and his ministers to grant the Romanians autonomy as a right which they had earned through their sacrifices on behalf of the imperial cause.

Their efforts came to nought, for no Austrian official was prepared to recognize the principle of nationality, which had almost destroyed the empire. Iancu was profoundly disillusioned. He withdrew from public life and spent the remainder of his years in his beloved Apuseni Mountains. Like young forty-eighters throughout Europe, he had believed in the swift and glorious transformation of society. And like them, he had misjudged the pace of history. He had foreseen the disintegration of the old regime before he had any right to expect it, and, thus, the failure of history to turn at its assumed turning-point had been a shattering experience.

Iancu as Prefect of the Auraria Gemina Legion, made up of Moţi recruits and based at Câmpeni.

Avram Iancu died on September 10, 1872 at Baia de Criș. His body was buried, according to his wish, under Horea's tree in Țebea (by tradition, the place where the Revolt of Horea, Cloșca and Crișan had started)

Avram Iancu was officially declared as a Hero of the Romanian Nation.

Comments

erepublik.com/en/article/2685055

erepublik.com/ro/article/2685055

Pig Benis

Már megint ez a magyargyűlölő román

-Sue me!

Votat

I did not know that axe-wielding heachoppers, murderers of children, old people and women are so popular in Romania.

But then, I reminded myself: de gustibus...

So Iancu helped the Habsburg imperium agains the hungarian revolution, and after he realized what a stupid decision he made by fighting the wrong, he went crazy.

That's such a sad story of a wannabe-hero who lost everything.

(If i would have been a hungarian revolution leader that times, probably i would have given the romanians the equal rights. At the and we would have been fighting together and maybe winning, or -probably- loosing together. Even if loosing, it would have been a much better story then fighting each other and loosing both of us for sure. The austrians used very vell the "divide and conquer" method)