Who were they ? - Assassins

•

by

•

by SabatonBIH

The Assassins (Persian: حشاشين Ḥashshāshīn, also Hashishin, Hassassin, or Hashashiyyin) were an order of Nizari Ismailis, particularly those of Persia and Syria that formed around 1091. Posing a strong military threat to Sunni Seljuq authority within the Persian territories, the Nizari Ismailis captured and inhabited many mountain fortresses under the leadership of Hassan-i Sabbah.The Assassins' cult is a good example of the diversity of unconventional means to reach and build a parallel political power of a certain magnitude. Hassan Sabbah was neither prince nor king. He didn't rule over any country or nation in particular, he was just the leader of an islamic religious cult: the Ismailis. Even though the origin and the base of his power are not a nation-state, the Old Man of the Mountain and his Assassins will have a great influence in the Middle East from the XIth till the end of the XIIIth century.

The name "Assassin" is often said to derive from the Arabic Hashishin or "users of hashish",[1] to have been originally derogatory and used by their adversaries during the Middle Ages.

The Masyaf branch of the Assassins was taken over by the Mamluk Sultan Baibars in 1273. The Mamluks however, continued to use the services of the remaining Assassins: Ibn Battuta reported in the 14th century their fixed rate of pay per murder. In exchange, the higher authorities allowed them to exist. The mention of Assassins were also preserved within European sources, such as the writings of Marco Polo, in which they are depicted as trained killers, responsible for the systematic elimination of opposing figures.

Origins

The origins of the Assassins trace back to just before the First Crusade around 1080. It is difficult to find out much information about the origins of the Assassins because most early sources are either written by enemies of the order or based on legends. Most sources dealing with the order's inner working were destroyed with the capture of Alamut, the Assassins' headquarters, by the Mongols in 1256. However, it is possible to trace the beginnings of the cult back to its first Grandmaster, Hassan-i Sabbah.

A passionate devotee of Isma'ili beliefs, Hassan-i Sabbah was well-liked throughout Cairo, Syria and most of the Middle East by other Isma'ili, which led to a number of people becoming his followers. Using his fame and popularity, Sabbah founded the Order of the Assassins. While his motives for founding this order are ultimately unknown, it was said to be all for his own political and personal gain and to also exact vengeance on his enemies. Because of the unrest in the Holy Land caused by the Crusades, Hassan-i Sabbah found himself not only fighting for power with other Muslims, but also with the invading Christian forces.[2]

After creating the Order, Sabbah searched for a location that would be fit for a sturdy headquarters and decided on the fortress at Alamut in what is now northwestern Iran. It is still disputed whether Sabbah built the fortress himself or if it was already built at the time of his arrival. In either case, Sabbah adapted the fortress to suit his needs of not only defense from hostile forces, but also indoctrination of his followers. After laying claim to the fortress at Alamut, Sabbah began expanding his influence outward to nearby towns and districts, using his agents to gain political favour and intimidate the local populations.

Spending most of his days at Alamut working on religious works and doctrines for his Order, Sabbah was never to leave his fortress again in his lifetime. He had established a secret society of deadly assassins, which was built in a hierarchical format. Below Sabbah, the Grand Headmaster of the Order, were those known as "Greater Propagandists", followed by the normal "Propagandists", the Rafiqs ("Companions"), and the Lasiqs ("Adherents"). It was the Lasiqs who were trained to become some of the most feared assassins, or as they were called, "Fida'i" (self-sacrificing agent), in the known world.[3]

It is, however, unknown how Hassan-i-Sabbah was able to get his "Fida'i" to perform with such fervent loyalty. One theory, possibly the best known but also the most criticized, comes from the observations from Marco Polo during his travels to the Orient. He describes how the "Old Man of the Mountain" (Sabbah) would drug his young followers with hashish, lead them to a "paradise", and then claim that only he had the means to allow for their return. Perceiving that Sabbah was either a prophet or some kind of magic man, his disciples, believing that only he could return them to "paradise", were fully committed to his cause and willing to carry out his every request.[4] (However, this story is disputed due to the fact that Sabbah died in 1124 and Sinan, who is frequently known as the "Old Man of the Mountain", died in 1192. Marco Polo wasn't born until 1254.) With his new weapons, Sabbah began to order assassinations, ranging from politicians to great generals. Assassins rarely would attack ordinary citizens though and tended not to be hostile towards them. All Hashashins were trained in both the art of combat as in the study of religion, believing that they were on a jihad and were religious warriors. Some consider them the Templars of Islam[5] and, as such, also formed an order with varying degrees of initiation.

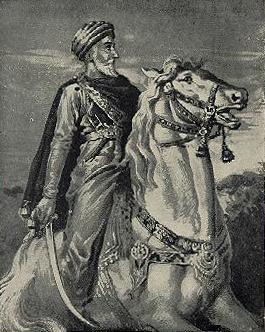

Picture of Hassan-i Sabbah

Although the "Fida'i" were the lowest rank in Sabbah's order and only used as expendable pawns to do the Grandmaster's bidding, much time and many resources were put in to training them. The Assassins were generally young in age giving them the physical strength and stamina which would be required to carry out these murders. However, physical prowess was not the only trait that was required to be a "Fida'i". To get to their targets, the Assassins had to be patient, cold, and calculating. They were generally intelligent and well read because they were required to possess not only knowledge about their enemy, but his or her culture and their native language. They were trained by their masters to disguise themselves, sneak in to enemy territory and perform the assassinations instead of simply attacking their target outright.[3]

As tensions in the Middle East grew during the Crusades, the Assassins were also known for taking contracts from outside sources on either side of the war, whether it was from the invading Crusaders or the Saracen forces, so long as the assassination fit in to the Grandmaster's plan.

Assassination

In their peak, much of the assassinations of the day were often attributed to the hashashin. Even though the Crusaders and the other factions employed personal assassinations, the fact that hashashins performed their assassination in full view of the public gave them the reputation affiliated to them.[13] Officers of both the Crusaders and Saracen were forced to remain continuously armed for personal protection. Islamic historian Bernard Lewis cites the roll of honor at Alamut containing the names of fifty well-performed assassinations of known political enemies during the thirty-five years reign of Hassan.[Wasserman 3] Hashashins executed those who represented a threat to the Nizari cause and Islam, but would rarely attack ordinary citizens though and tended not to be hostile towards them. They favored one single assassination than the wide bloodshed of actual combat. Genocide was not tolerated, and the hashashins believed that large political assassinations would bring peace and a true sense of security to the common people. Slaying innocents and civilian bystanders who did not need to die could spread strife and discord, in addition to ruining the name of the Nizari order.[13]

Sir Conrad of Montferrat is one of the well known victims of the hashashin. While strolling in the courtyard of the fortress city of Tyre with an entourage of mailed knights, two hashashins dressed as Christian monks walked towards the center of the courtyard, and with daggers raised, stabbed Conrad twice, killing him. Although the mystery of who were the hashahsin's employers, it is much attributed to King Richard the Lionheart and Henry of Champagne. The English King Edward Longshanks himself was seriously wounded within an inch of his life by the blade of a hashashin outside the walls of Jerusalem. Abul-Mahasin Ruyani, a famed Sunni teacher, was assassinated in 1108 because of simply insulting the hashashins with his anti-Nizari preachings.

Psychological warfare, and attacking the enemy's psyche was another often employed tactics of the hashashins, who would sometimes attempt to draw their opponent to submission than risking to kill it.[14] Saladin himself managed to survive two assassination attempts. Although surviving these assassinations, it put him in a state of paranoia fear of another attempt on his life. During a night in his conquest on Masyaf, Saladin woke-up from his sleep to find a figure leaving his tent. He then saw that the lamps were displaced and beside his bed laid hot scones of the shape peculiar to the hashashins with a note at the top pinned by a poisoned dagger. The note threatened that he would be killed if he didn't withdraw from his assault. He later accuses a hashashin to be the figure. Saladin later told his guards to settle a truce with the hashashins.

During the Seljuk invasion after the death of Muhammad Tapar, a new Seljuk sultan emerged with the coronation of Tapar's son Sanjar. When Sanjar rebuffed the hashashin ambassadors who were sent by Hassan for peace negotiations, Hassan sent his hashashins to the sultan. Sanjar woke up one morning with a dagger stuck in the ground beside his bed. Alarmed, he kept the matter a secret. A messenger from Hassan arrived and stated, "Did I not wish the sultan well that the dagger which was struck in the hard ground would have been planted on your soft breast". For the next several decades there ensued a ceasefire between the Nizaris and the Seljuk. Sanjar himself pensioned the hashashins on tax collected from the lands they owned, gifted them with grants and licenses, and even allowed them to collect tolls from travelers.

Legends and folklore

The legends of the Assassins had much to do with the training and instruction of Nizari fida'is, famed for their public missions during which they often gave their lives to eliminate adversaries. Misinformation from the Crusader accounts and the works of anti-Ismaili historians have contributed to the tales of fida'is being fed with hashish as part of their training.[15] Whether fida'is were actually trained or dispatched by Nizari leaders is unconfirmed, but scholars including Vladimir Ivanov purport that the assassination of key figures including Saljuq vizier Nizam al-Mulk likely provided encouraging impetus to others in the community who sought to secure the Nizaris from political aggression.[15] In fact, the Saljuqs and Crusaders both employed assassination as a military means of disposing of factional enemies. Yet during the Alamut period almost any murder of political significance in the Islamic lands became attributed to the Ismailis.[Daftary 9] So inflated had this association grown, that in the work of orientalist scholars such as Bernard Lewis the Ismailis were virtually equated to the politically active fida'is. Thus the Nizari Ismaili community was regarded as a radical and heretical sect known as the Assassins.[11] Originally, a "local and popular term" first applied to the Ismailis of Syria, the label was orally transmitted to Western historians and thus found itself in their histories of the Nizaris.[12]

The tales of the fida'is' training collected from anti-Ismaili historians and orientalists writers were confounded and compiled in Marco Polo's account, in which he described a "secret garden of paradise".[Daftary 10] After being drugged, the Ismaili devotees were said be taken to a paradise-like garden filled with attractive young maidens and beautiful plants in which these fida'is would awaken. Here, they were told by an "old" man that they were witnessing their place in Paradise and that should they wish to return to this garden permanently, they must serve the Nizari cause.[12] So went the tale of the "Old Man in the Mountain", assembled by Marco Polo and accepted by Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall, an 18th century Austrian orientalist writer responsible for much of the spread of this legend. Until the 1930s, von Hammer's retelling of the Assassin legends served as the standard account of the Nizaris across Europe.[Daftary 11]

Another one of Hassan's recorded methods includes hashashins appear to have been vilified by their contemporaries. One story goes that Hassan al-Sabah set up a trick to make it appear as if he had decapitated one of his hashashins and the "dead" hashashin's head lay at the foot of his throne.[16] It was actually one of his men buried up to his neck covered with blood. He invited his hashashins to speak to it. He said that he used special powers to allow it to communicate. The supposed talking head would tell the hashashins about paradise after death if they give all their full hearts to the cause. After the trick was played, Hassan had the man killed and his head placed on a stake to cement the deception.

A well-known legend tells of Count Henry of Champagne, returning from Armenia, spoke with Hassan at Alamut. The count claimed to have the most powerful army and at any moment could defeat the Hashshashin, as its army was 10 times larger. Hassan replied that his army was indeed the most powerful, and to prove he told one of his men to jump off from the top of the castle in which they were. The man did. Surprised, the count had only to recognize that Hasan had the strongest army, because they did everything at his command, and Hassan further gained the count's respect.[17]

Modern works on the Nizaris have elucidated the history of the Nizaris and in doing so, dispelled popular histories from the past as mere legends. In 1933, under the direction of the Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah, Aga Khan III, the Islamic Research Association was developed. Historian Vladimir Ivanov was central to both this institution and the 1946 Ismaili Society of Bombay. Cataloguing a number of Ismaili texts, Ivanov provided the ground for great strides in modern Ismaili scholarship.[Daftary 12]

In recent years, Peter Willey has provided interesting evidence against the Assassin folklore of earlier scholars. Drawing on its established esoteric doctrine, Willey asserts that the Ismaili understanding of Paradise is a deeply symbolic one. While the Qur'anic description of Heaven includes natural imagery, Willey argues that no Nizari fida'i would seriously believe that he was witnessing Paradise simply by awakening in a beauteous garden.[Willey 4] The Nizaris' symbolic interpretation of the Qur'anic description of Paradise serves as evidence against the possibility of such an exotic garden used as motivation for the devotees to carry out their armed missions. Furthermore, Willey points out that a courtier of Hulagu Khan, Juvayni, surveyed the Alamut castle just before the Mongol invasion. In his reports about of the fortress, there are elaborate descriptions of sophisticated storage facilities and the famous Alamut library. However, even this anti-Ismaili historian makes no mention of the gardens on the Alamut grounds.[Willey 5] Having destroyed a number of texts of the library's collection, deemed by Juvayni to be heretical, it would be expected that he would pay significant attention to the Nizari gardens, particularly if they were the site of drug use and temptation. Having not once mentioned such gardens, Willey concludes that there is no sound evidence in favour of these fictitious legends.

These legends feature in certain works of fiction, including Vladimir Bartol's 1938 novel Alamut, and Simon Acland's[18] First Crusade novels The Waste Land and The Flowers of Evil. In the latter the author suggests that the origin of the name Assassin is the Turkish word hashhash meaning opium, partly on the basis that this drug is more suitable for producing the effects suggested in the legends than hashish.

Alamut

About Hassan-i Sabbah

Hassan-i Sabbāh ( / Ḥasan-e Ṣabbāh; Arabic: حسن الصباح / Ḥasan aṣ-Ṣabbāh; 1050s–1124) was a Nizārī Muslim missionary from Persia[1][2] who converted a community in the late 11th century in the heart of the Alborz Mountains of northern Iran. The place was called Alamut and was attributed to an ancient king of Daylam. He founded a group whose members are sometimes referred to as the Hashshashin or "Soldiers" to protect from attackers outside of Iran.

His search for a base from where to guide his mission ended when he found the castle of Alamut in the Rudbar area in 1088, modern day 'Qazvin, Iran'. It was a fort that stood guard to a valley that was about fifty kilometers long and five kilometers wide. The fort had been built about the year 865; legend has it that it was built by a king who saw his eagle fly up to and perch upon a rock, of which the king, Wah Sudan ibn Marzuban, understood the importance. Likening the perching of the eagle to a lesson given by it, he called the fort Aluh Amut: the "Eagles Teaching".

Hassan’s takeover of the fort was one of silent surrender in the face of defeated odds. To effect this takeover Hassan employed an ingenious strategy: it took the better part of two years to effect. First Hassan sent his Daʻiyyīn and Rafīks to win the villages in the valley over. Next, key people were converted and in 1090 Hassan took over the fort. It is said that Hassan offered 3000 gold dinars to the fort owner for the amount of land that would fit a buffalo’s hide. The term having been agreed upon, Hassan cut the hide in to strips and link the strips around the perimeter of the fort. The owner was defeated. (This story bears striking resemblance to Virgil's account of Dido's founding of Carthage.) Hassan gave him a draft on the name of a wealthy landlord and told him to take the money from him. Legend further has it that when the landlord saw the draft with Hassan’s signature, he immediately paid the amount to the fort owner, astonishing him.

With Alamut as his, Hassan devoted himself so faithfully to study, that it is said that in all the years that he was there – almost 35, he never left his quarters, except the two times when he went up to the roof. He was studying, translating, praying, fasting, and directing the activities of the Daʻwa: the propagation of the Nizarī doctrine was headquartered at Alamut. He knew the Qur'ān by heart, could quote extensively from the texts of most Muslim sects, and apart from philosophy, he was well versed in mathematics, astronomy, alchemy, medicine, architecture, and the major science fields of his time.[7] Hassan was one who found solace in austerity and frugality.

From this point on his community and its branches spread throughout Iran and Syria and came to be called Hashshashin or Assassins, also known as the Fedayin (Meaning 'The Martyrs', or 'Men Who Accept Death'), a mystery cult.

SHOUT:

http://www.erepublik.com/en/article/who-were-they-assassins-2168128/1/20

Comments

♥ஜ We work in the dark, to serve the light. We are assassins.Nothing is true, everything is permitted 🙂 ஜ♥

Quando gli altri seguono ciecamente la verita' ricorda.. NULLA E' REALE.

Quando gli altri si piegano alla morale o alla legge ricorda.. TUTTO E' LECITO.

Agiamo nell'ombra per servire la luce, siamo assassini.. NULLA E' REALE, TUTTO E' LECITO.

❤

Brateeee

Drogeraši, kjafiri i šta sve ne...

Još kad si nabac'o, da si preveo..što bi to bilo dobro..Ovako mrsko mi prevodit ovako veliki tekst, a tema je i više nego zanimljiva...

uaaa kopiranje clanaka, vec bio kod jednog eAssassina uaaa : P

"Drogeraši, kjafiri i šta sve ne..."

x

tvorac hasisara nije tamo taj neki drogeras,vec seljo i crnjo.

damir zlaTu : neznam jel bio kod assassina al sigurno nisam kopirao njegov clanak 😃

zezam se ba : D nisi ti tad bio ni u eplanu kad je clanak pisan : P

haahah ,tako je 🙂

lan bu nasıl okunacak????*

tvorac hasisara nije tamo taj neki drogeras,vec seljo i crnjo. x2

Ja koliko se sjecam dnevni zadatak je bilo obilazenje biljaka,pricanje barem 10 minuta po jednoj biljci i dolaziti na skupove veseo,sto ej u sustini najlaksi posao biti samo se sjecam da je crnjo krao iz steka lafo ga koljeno boli,a znam ja sta je radio on po privatnim kanalimaa,li eto da izbjegnemo svadje.

mogao si prevest

tvorac hasisara nije tamo taj neki drogeras,vec seljo i crnjo. x3

preveo bi ja ali onda ne bi razumjeli ovi stranci ,ipak idem na malo veće tržište od BiH XD

♥ஜ We work in the dark, to serve the light. We are assassins.Nothing is true, everything is permitted ஜ♥ x2

Copy/paste.. Ne bas zanimljivo....+RL historija nije bas vazna do detalja.... (na ovo bi mogao lako i report dobiti)

Vjerovali ili ne, vise volim citati historiju eAssassinsa🙂

DROGA HAS BOG JE NAS !!!

Ja ne mogu da verujem. Čak i vaši "plaćenici" su zapravo islamski fundamentalisti. Bolestan narod...

Prosvjetli nas Tomo, tačno sam se zabrinuo da nema tvog komentara:/

hašišari ko hašišari, nemaju hašiša😃

Old school Hollywood,

Washed up Hollywood.