Rare photographs of Japanese pearl divers, 1950s

•

by

•

by Clark.Kent

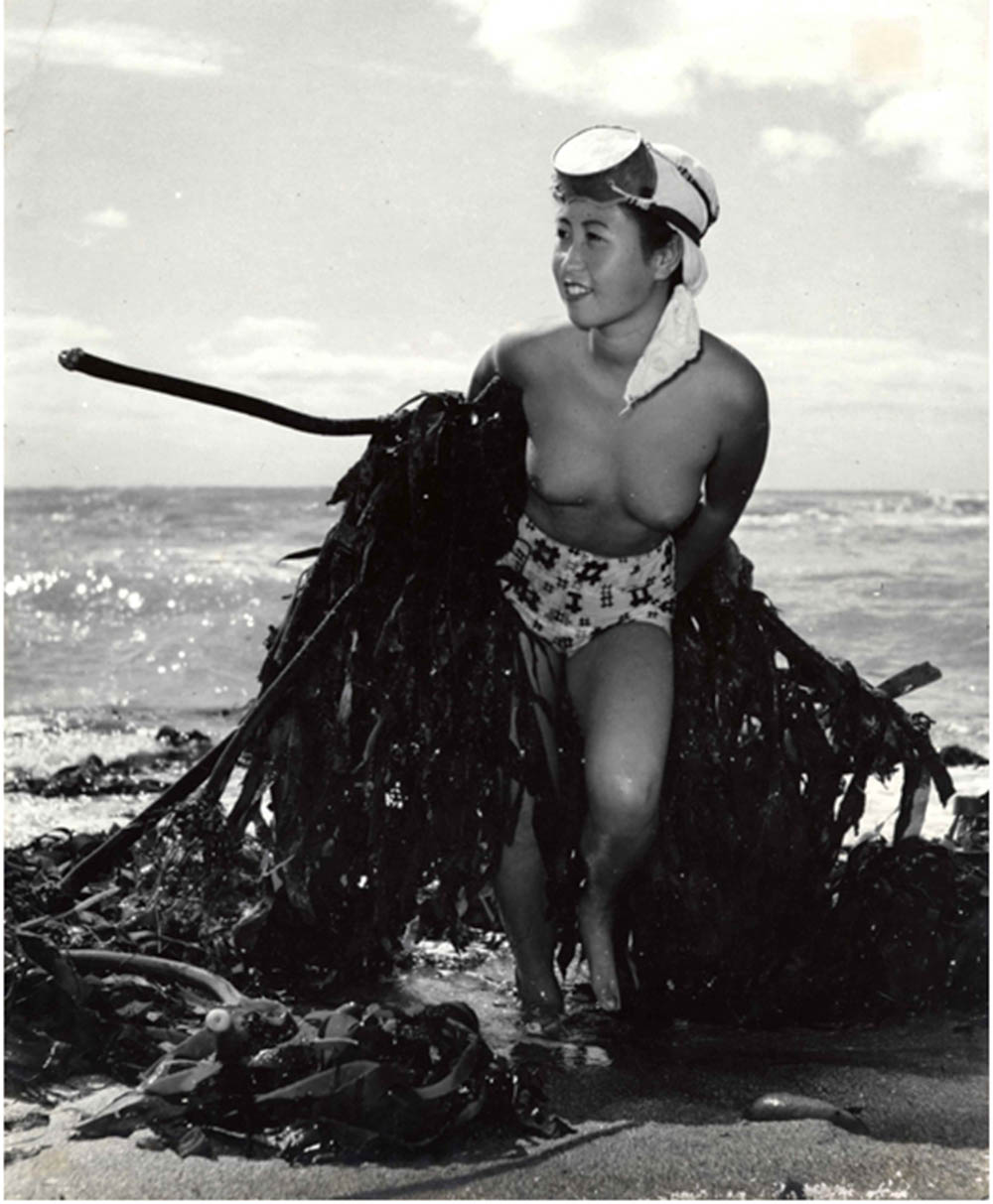

A Japanese skin diver or “ama” near the small fishing village of Onjuku in the Chiba prefecture of Japan, August 1959.

For nearly two thousand years, Japanese women living in coastal fishing villages made a remarkable livelihood hunting the ocean for oysters and abalone, a sea-snail that produces pearls.

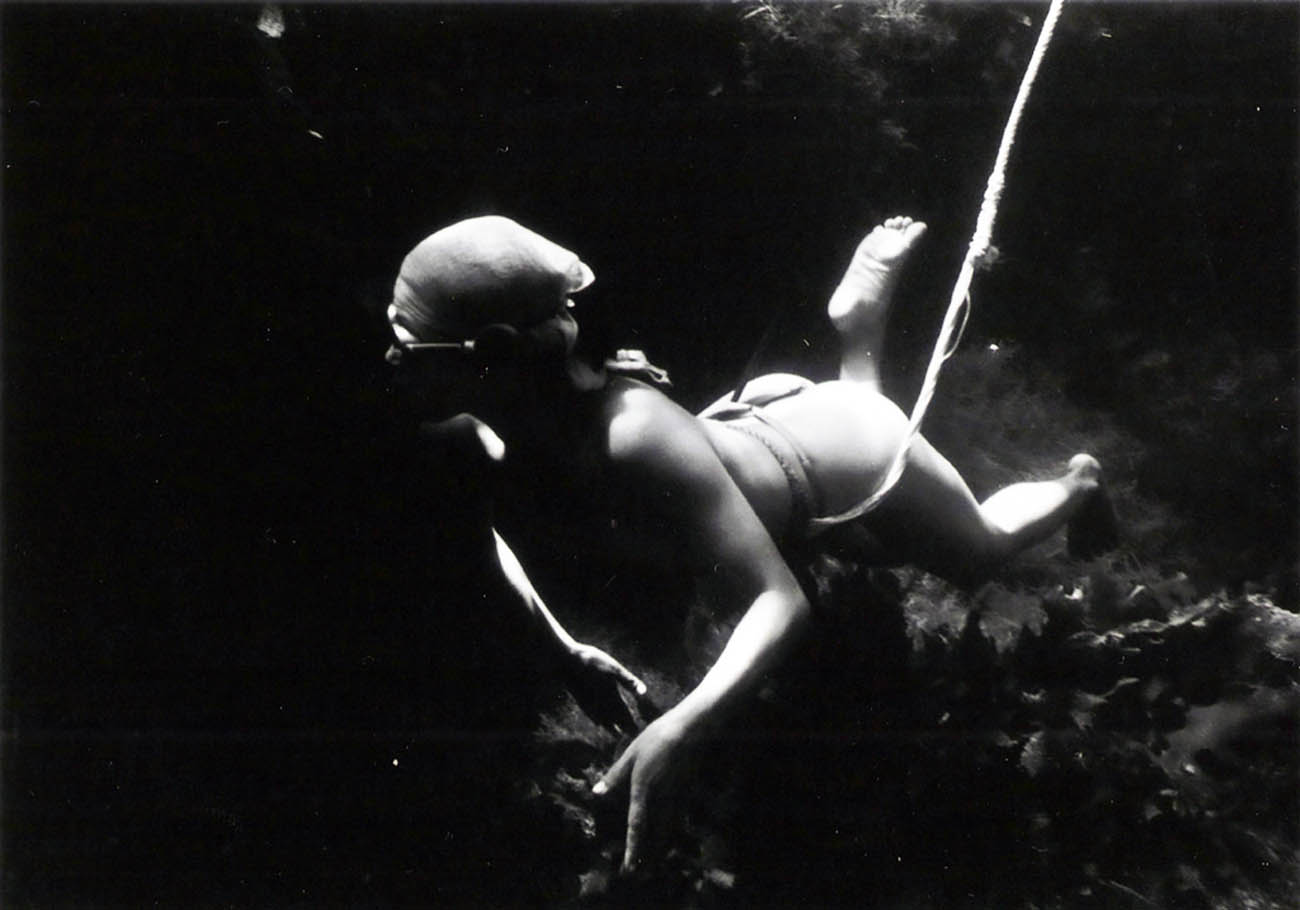

They are known as ama. Ama, meaning “sea woman”, are freedivers, women who make their living by diving to depths of up to 25 meters without using oxygen tanks or other breathing apparatus.

Instead, the ama relies on their own skill and breathing techniques to propel them to the bottom of the ocean and back to the surface again while holding their breath for up to two minutes at a time.

The history of the ama dates back at least 2000 years. There are references to the ama in famous texts such as the 8th century Man’yoshu collection of Japanese poetry and Sei Shonagon’s Pillow Book from the 10th century. The ama has also been immortalized in ukiyo-e woodblock prints from the Edo period.

The history of the ama dates back at least 2000 years.

Ama are famous for pearl diving, but originally they dived for food like seaweed, shellfish, lobsters, octopus, and sea urchins — and oysters which sometimes have pearls.

In the early 1900s goggles were introduced and quickly adopted by the ama.

There are various theories for the dominance of women as freedivers, some suggest that in ancient times there were equal numbers of male and female divers but when the men began to travel further out to sea in boats to pursue fishing the women stayed close to shore, diving for seaweed and shellfish at the bottom of the ocean and this tradition was passed down to the daughters and granddaughters.

The widely held belief among ama divers themselves is that women are able to withstand the cold water better because of extra layers of fat on their body and are therefore able to stay in the water for long periods and collect a bigger catch. Another reason is the self-supporting nature of the profession, allowing women to live independently and foster strong communities.

Perhaps most surprisingly, however, is the old age to which these women are able to keep diving. Most ama are elderly women (some even surpassing 90 years of age) who have practiced the art for many, many years, spending much of their life at sea.

Ama divers can keep diving well into old age.

This is the place where the divers gather in the mornings to prepare for the day, eating, chatting and checking their equipment.

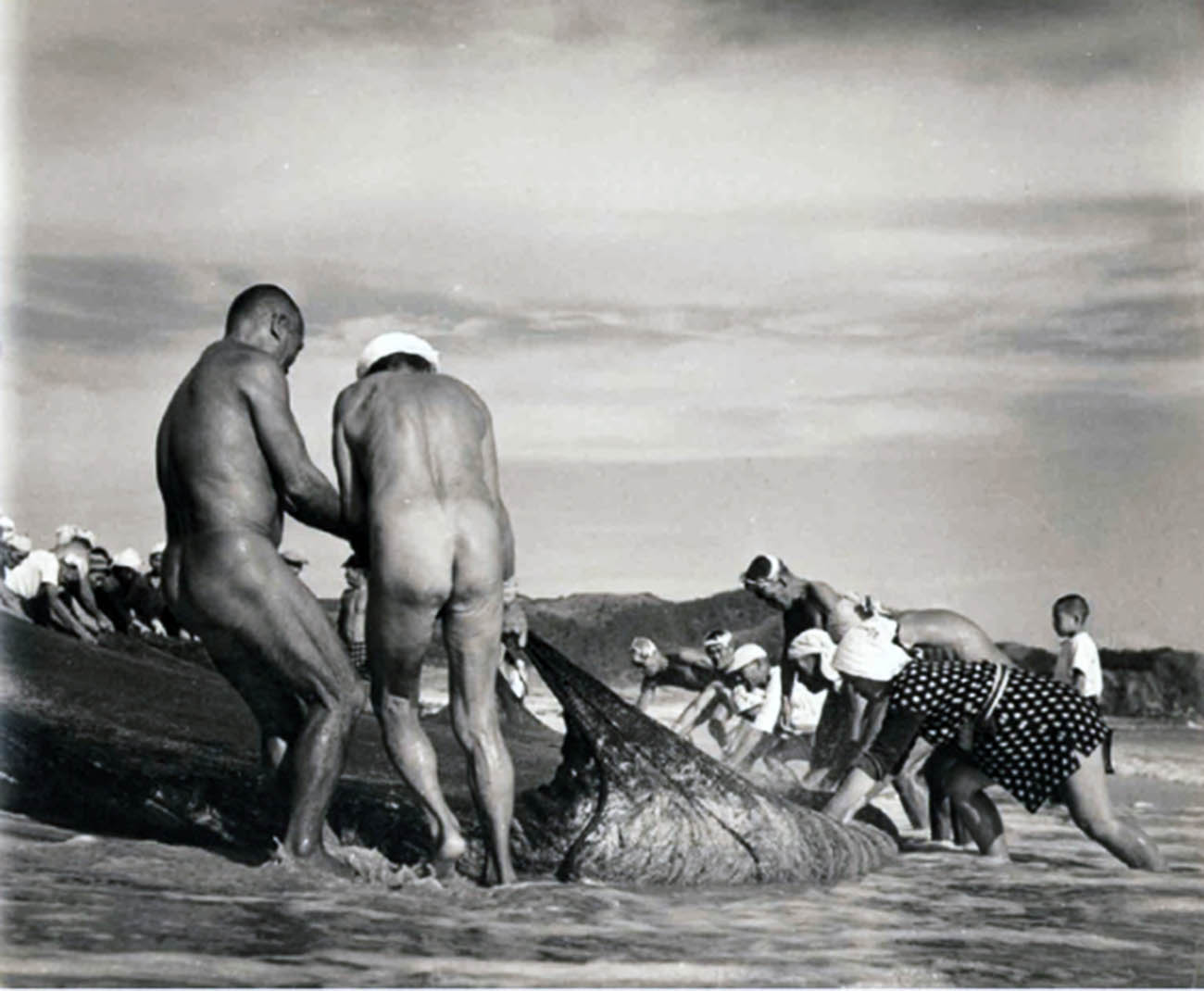

Ama divers pushing a boat out of water.

Traditional ama divers used a minimum amount of equipment.

Iwase Yoshiyuki photographs are thought to be the only comprehensive documentation of this near-extinct tradition in existence.

Traditional ama divers used a minimum amount of equipment, they usually wore only a fundoshi (loincloth) while diving to make it easier to move in the water and a tenugui (bandanna) around their head to cover their hair. The tenugui might also have good luck charms written on it to protect the diver from evil spirits.

Those divers who descended the deepest would also wear a weighted belt around their waist to aid their descent. The most important tool for divers searching for abalone (the most prized and lucrative catch) was the tegane or kaigane, a sharp spatula-like tool used to pry the stubborn abalone from the rocks.

In the early 1900s goggles were introduced and quickly adopted by the ama. Around this time air hoses and hand pumps were also introduced from abroad and used in shellfish diving in some regions but it quickly became obvious that a diver using such equipment could stay submerged for longer and would soon destroy the resource base.

In an effort to protect the abalone and prevent overfishing air apparatus were banned by the fisheries cooperatives that all commercial ama divers must belong to and the ban remains to this day.

Until the 1960s, many ama, especially those in villages along the Pacific Ocean coast of Japan, continued to dive wearing only fundoshi, or cotton shorts, a remarkable sight captured by Japanese photographer Iwase Yoshiyuki in his series of photographs taken on the Chiba peninsula in the first half of the twentieth century.

With the introduction of the wetsuit to Japan in the 1970s, the sight of a half-naked ama diver became rare and wetsuits are now an accepted form of equipment for diving.

During the diving season, life for the ama revolves around the ama hut, or amagoya. This is the place where the divers gather in the mornings to prepare for the day, eating, chatting, and checking their equipment. After diving, they return to the hut to shower, rest and warm their bodies to recover from their day’s work.

The atmosphere in the hut is one of relaxation and camaraderie, for six months of the year the women are free from the usual familial and social duties they are expected to perform, and they are able to connect with other women who share their love of the ocean and diving.

The amagoya was also a place of learning for novice divers. Unlike other traditional crafts, there is no formal apprentice-style system of training for ama divers.

While diving skills such as breathing techniques can be acquired relatively easily through practice, the most valuable knowledge, that of the best places to find abalone are a closely guarded secret, even between mother and daughter divers.

However, in the amagoya, by listening to the more experienced divers’ recap of their day, novice divers could begin to gather valuable knowledge about the local reef environment and therefore where the most abalone are likely to be found.

While ama gather various foods such as seaweed, shellfish, and sea urchin, it is the abalone that is most prized and lucrative. In the heyday of abalone diving in the 1960s, a skillful ama could earn as much as 80,000 US dollars in a six-month diving season. As a result, talented ama were viewed as highly eligible and could take their pick of the local men when choosing a husband.

Unfortunately, with the decline of abalone stocks the earning power of the ama has also been reduced. Despite the efforts of the fisheries cooperatives to preserve precious resources through restricted diving hours, bag limits, and size regulations, outside factors such as pollution and global warming have harmed the environment and affected the growth of abalone.

While in the past it may have been possible to make a good living from abalone diving alone, most ama now dive to supplement their main income of farming or other work.

Comments

Interesting. 😁

))

double food first comment

Successfully transferred 400 item(s) to Joker from Bosnia.

o7! Top!

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to RiccardoCatte.

o7

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to Fenoglioteam.

yeah! interesting!!!! o7!

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to GioPiva.

o7

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to riyo86.

Amazing! (:

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to Tomi_ur.

Thanks! o/ Keep writing articles!

o7

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to PiraPir.

Shared in Japan!

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to Darshu.

Amazing women 🙂

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to B l u e.

dankeschön

this is a comment o7

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to MldStefan.

Brave work.

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to Dioist.

Comment

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to Ivan Petrof.

Truly interesting article. Thank you

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to Dr Druid.

Awesome

Thanks for this article

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to AmirCrowley.

Great article and photos!

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to Dr.Male.

hue /o

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to FragUK.

boobiess

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to Bosniak Turk.

O7

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to Galaxy2100.

interesting

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to Noel de Never 12.

Nic bo... I mean pearls. Nice pearls

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to The Real Elefantescu.

very interesting

tx for ur support ))

😎

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to Minho Village.

Thanks for this article

o7

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to IArhangeLLorDI.

Votado

07

Successfully transferred 200 item(s) to Obi Wan Simio.