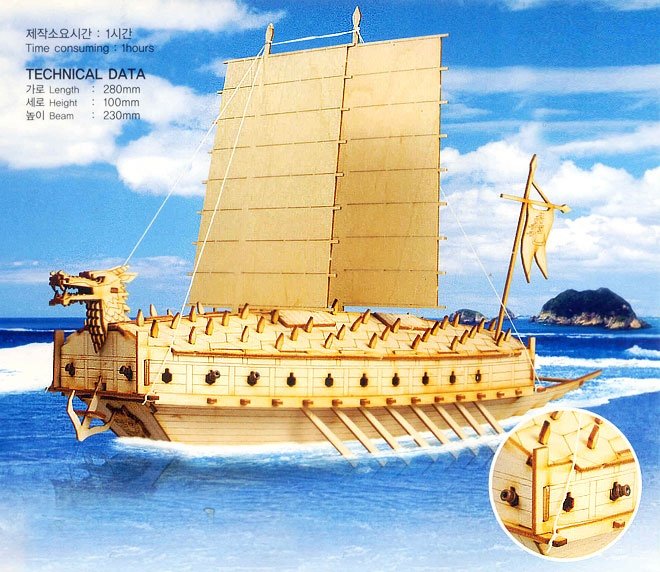

Kobukson (거북선) : Miraculous Large Ancient Korea Tactical Ship

•

by

•

by EternalLightStream

Here is the legendary korean ship Kobukson specification :

Name : Turtle boat(Geobukseon)

Builders : Yi Sun-sin, Lt. Na Dae Yong

Operators : Joseon Dynasty

Built : circa 1590

In service : Circa 16th century Saw action actively during Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–159

😎

Completed : 20-40 units deployed,

Lost : unknown number sank in Battle of Sacheon (1592)

Preserved : replicas only in museums

Laid down : March 12, 1592

Launched : March 27, 1592

In service : May 15, 1592

Class and type : Panokseon type

Length : 100 to 120 feet

Beam : 30 to 40 feet

Propulsion : 80 oarsmen

Complement : 50 soldiers

Armament : sulfur gas thrower, iron spikes, 26 cannons

Notes :

in full operational conditions cannons ranged between 200 yds to 600 yds

The Turtle ship, also known as Geobukseon or Kobukson (거북선), was a type of large warship belonging to the Panokseon class in Korea that was used intermittently by the Royal Korean Navy during the Joseon Dynasty from the early 15th century up until the 19th century.

The first references to older, first generation turtle ships, known as Gwiseon (귀선; 龜船), come from 1413 and 1415 records in the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty, which mention a mock battle between a gwiseon and a Japanese warship. However, these early turtle ships soon fell out of use as Korea’s naval preparedness decreased during a long period of relative peace.

Turtle ships participated against Japanese naval forces that supported Toyotomi Hideyoshi's attempts to conquer Korea from 1592-1598. However, their historical role may have been exaggerated since "the entire Korean fleet probably did not have more than half a dozen turtleboats in action at any one time". Korean admiral Yi Sun-sin is credited with designing the ship. His turtle ships were equipped with at least five different types of cannon. Their most distinguishable feature was a dragon-shaped head at the bow (front) that could launch cannon fire or flames from the mouth. Each was also equipped with a fully covered deck to deflect arrow fire, musket-shots, and incendiary weapons. The deck was covered with iron spikes to discourage enemy men from attempting to board the ship

According to the Nanjung Ilgi, Yi's wartime diary, Yi decided to resurrect the turtle ship in 1591, from pre-existing designs (see picture, illustrated nearly 200 years earlier), after discussing the matter with his subordinates. Once concluding that a Japanese invasion was possible, if not imminent, Yi and his subordinate officers, among whom Na Dae-yong (羅大用) is named as the chief constructor,constructed the first modern turtle ship. Yi's diary, along with the book entitled Hangrok written by his nephew Yi Beon, described numerous important details about the structures, construction progress, and the use of turtle ships in battle, as well as the testing of weaponry used in the ships.

The mounted weapons, Korean cannons with ranges from about 300 to 500 metres, were tested on March 12, 1592. Yi completed his first turtle ship and launched it on March 27, 1592, one day before the Siege of Busan and the Battle of Tadaejin.

Many different versions of the turtle ships served during the war, but in general they were about 100 to 120 feet long (30 to 37 metres), and strongly resembled the Panokseon's bottom structure. The turtle ship was technically a hull that was placed on top of a Panokseon, with a large anchor held in the front of the ship, and other minor modifications.

On the bow of the vessel was mounted a dragon head which emitted sulfur smoke to effectively hide its movement from the enemy in short distance combat. The dragon head, which is considered the most distinguishing feature of the vessel, was large enough for a cannon to fit inside. The dragon head served as a form of psychological warfare, with the aim of striking fear into the hearts of Japanese sailors. Early versions of the turtle ship would burn poisonous materials in the dragon's head to release a poisonous smoke.

In the front of the ship was a large anchor. Below the anchor was a wooden crest that was shaped like a face, and these were used to ram into enemy ships.

Similar to the standard Panokseon, the turtle ship had two masts and two sails. Oars were also used for maneuvering and increased speed. Another advantage the turtle ship had over its enemies was that the turtle ship could turn on its own radius.

The turtle ship had 10 oars and 11 cannon portholes on each side. Usually, there was one cannon porthole in the dragon head's mouth. There were two more cannon portholes on the front and back of the turtle ship. The heavy cannons enabled the turtle ships to unleash a mass volley of cannonballs (some would use special wooden bolts several feet in length, with specially engineered iron fins). Its crew complement usually comprised about 50 to 60 fighting marines and 70 oarsmen, as well as the captain.

Sources indicate that sharp iron spikes protruded from hexagonal plates covering the top of the turtle ship. An advantage of the closed deck was that it protected the Korean sailors and marines from small arms and incendiary fire. The spikes discouraged Japanese sailors from engaging in their primary method of naval combat at the time, grappling an enemy ship with hooks and then boarding it to engage in hand-to-hand combat.

Korean written descriptions all point to a maneuverable ship, capable of sudden bursts of speed. Like the standard Panokseon, the turtle ship featured a U-shaped hull which gave it the advantage of a more stable cannon-firing platform, and the ability to turn within its own radius. The main disadvantage of a U-shaped bottom versus a V-shaped bottom was a somewhat slower cruising speed.

Tactical use :

Yi resurrected the turtle ship as a close-assault vessel, intended to ram enemy ships and sink them, similar to their use in past centuries. Despite smaller numbers, disabling or sinking enemy's lead command ship could severely damage command structure and morale of the enemy fleet. After ramming, the turtle ship would unleash a broadside volley of cannonballs. Because of this tactic, the Japanese called the turtle ships the mekurabune (目蔵船), or "blind ships", because they would blast and ram into enemy ships. This kind of attack was used during the Dangpo Battle and Battle of Sacheon (1592).

The turtle ship's main use of the plating was as an anti-boarding device, due to the top plating of the turtle ship and its protruded spikes. Grappling hooks could not gain direct hold on the plating, and jumping on top of the turtle ship often meant being impaled. The heavy timber plating deflected arrows and arquebus rounds.

Later, the turtle ship was used for other purposes such as spearheading attacks or ambushing Japanese ships in tight areas such as in the Battle of Noryang.

Despite popular depiction, the turtle ship was not an extremely slow ship. The turtle ship had oar propulsion as well as sails, and could turn on its axis like the panokseon. Admiral Yi constructed the turtle ship to be fast and agile for the purpose of ramming.

History :

During the first year of the invasion, Admiral Yi engaged in ten successive naval victories that decimated the Japanese navy. At the battle of Okp'o, the Admiral's first victory, the Korean navy destroyed 31 out of 50 Japanese ships and only suffered one slight wound to one of its own sailors. Over the course of the next five battles, the Japanese lost 83 ships while the Koreans lost only 11 sailors. The next two battles, waged over a four-day period, are known together as the Battle of Hansan Island. It is regarded to be one of the three great Korean victories in the struggle against the Japanese13. In this battle, the Japanese navy lost 101 ships and more than 250 men, as opposed to 19 men lost on the Korean side. Admiral Yi won his ninth victory at the Battle of Pusan-p'o. His fleet of 92 ships, spearheaded by the turtle ship, encountered 470 Japanese vessels and sunk 100 of them while only losing only seven of his own sailors. A few months later, the Korean navy defeated the Japanese fleet at Ungp'o. With this tenth successive naval victory, Admiral Yi was appointed Supreme Naval Commander of the Three Southern Provinces14.

It should be pointed out that although the Japanese navy had a far greater number of ships and sailors than the Korean navy had, the Japanese navy was never a match for the superior Korean navy. The Japanese navy was made up mostly of trading vessels manned by sailors who had been pirates before the war. These men were not experienced with the forms of engagement that they witnessed in the Korean campaigns, and their ships were not equipped for such battles. Also, the Japanese naval commanders were unfamiliar with the waters along Korea's southern coastline, making it difficult for them to maneuver effectively. On the other hand, the Korean navy was composed of vessels built from knowledge gained while fighting against the Japanese pirates during the previous decades. Korean naval commanders and sailors also had received valuable training during this period, and their familiarity with the tides, currents, and obstacles of their home waters put them at a great advantage against the Japanese invaders15.

Under the leadership of Admiral Yi, the Korean navy was able to turn the tide of the invasion by cutting off the vital sea routes of the Japanese navy. Control of the Tsushima Strait and the numerous islets along Korea's southern coast had been an essential element of Hideyoshi's invasion strategy. Achieving this control would have given the Japanese navy access to the Yellow Sea, making it possible to re supply the Japanese troops in Seoul and P'yongyang by water; this would have also made it possible to set up fast communication links between Japan's northern and southern forces. With Korea in control of its own seas, Japan was forced to commit its navy to defending a narrow supply corridor between Kyushu and Pusan. From Pusan, the Japanese re supplied their northern forces via a precarious land route through central Korea. This method required much greater manpower than the sea route, and the Japanese supply lines were in constant threat of ambush by Korean guerrilla units16.

Within the first three months of the war, the Japanese invasion force had advanced up the Korean peninsula from Pusan in the south to the Yalu River in the north, capturing the major cities of Seoul and P'yongyang and routing the Koreans in every battle. The beleaguered Korean regular army, lacking leadership and morale, was scattered throughout the countryside into disorganized units. For a time, Korea was left virtually defenseless.

It was at this juncture that a guerrilla movement spontaneously began to develop all over Korea. Koreans from all walks of life joined guerrilla units that formed in their local districts and took up arms in the defense of their homeland. These guerrilla units were composed primarily of farmers and slaves and were typically led by either local gentry or respected Neo-Confucianists. Each unit generally was made up of a small number of men armed with swords and other light weapons; however, there were hundereds of these units throughout Korea.

Bands of guerrills repeatedly harassed Japanese communication and supply lines and attacked Japanese army columns using hit and run tactics. By the end of 1592 Korean guerrillas had succeeded in pushing the Japanese out of many towns and provinces throughout the country. At times more than one guerrilla unit joined with a reorganized Korean regular army unit to form a formidable host against the Jpanese invaders. In one instance a Korean force that had retaken a strategic fort at Haengju along the Han Rivernear Seoul fought back repeated attacks by a much larger Japanese force. The Korean victory at Haengju is also remembered to be one of the three great Korean victories against the Japanese. The Korean guerrilla movement that emerged, after the initial gains of the Japanese army, succeeded in stalling the momentum of the invasion and putting the Japanese on the defensive17.

Coupled with the successes of the Korean guerrilla movement was the entrance of the Chinese Ming army into the war. China finally came to the aid of Korea after repeated please by King Sonjo and after the Japanese army had already reached Korea's border with China. China was somewhat obligated to come to the assistance of Korea because Korea was a vassal state of China. Also, the threat of an invasion by Japan into China could not be tolerated. The first Chinese relief army of a mere 3000 troops arrived in Korea with the aim of retaking P'yongyang and was easily defeated by the Japanese occupiers. China then realized the seriousness of the situation that had developed in Korea, and they began to mobilize a much larger force to deal with the invading Japanese. In February of 1593, a Ming army of 50,000 soldiers attacked the Japanese defenses at P'yongyang and succeeded in pushing them all the way to Seoul before the Japanese counterattacked. Thus, a stalemate developed with the Chinese army in control of northern Korea and the Japanese in control of the central portion of the southern part of Korea from Seoul to Pusan.

At this point, informal talks were held between China and Japan, with the exclusion of Korea, to discuss the conditions for peace. After China threatened to send a 400,000 man army to Korea, Japan agreed to withdraw from Seoul and most of the Korean peninsula. By May of 1593, Japan retreated to a narrow defensive position along Korea's southern coast around Pusan, and formal peace talks were held. The peace talks between China and Japan over the fate of Korea were to last four years18.

China began the truce by sending emissaries to Japan to discuss peace between the two countries. General Hideyoshi was under the impression that Japan had won the war, so he gave his representatives at the peace talks a list of conditions for peace that were to be given to the Chinese delegation. These conditions included that the four southern Korean provinces were to be ceded to Japan, that a daughter of the Chinese emperor was to be wedded to the Japanese emperor, and that a Korean prince and several high ranking Korean officials were to be turned over to Japan as hostages to guarantee that the Korean government would no longer oppose Japan. Due to political intrigue on both the Chinese and Japanese sides, these conditions were not presented to the Ming emperor. Instead, a forged letter from Hideyoshi was given to the Ming emperor begging for peace and requesting that Japan be recognized as a vassal to China

Moral from this war story :

Never underestimate your enemies.

Bonus :

KOBUKSON GANG BANG STYLE !!

Comments

I Love Navy \o/

good article~

Wow, this probably beats the article in Wikipedia in terms of pictures.

The strongest battle ship in Age of Empire xD

GOOD~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Cool

V !!

v...는 했지만 머라하는지 모르겠다...;;; 일기에도 너무 길고...그냥 가만히 있....;;;

V

V 😃

V